Comic Timing in Angoulême: Le Festival International de la Bande Dessinée

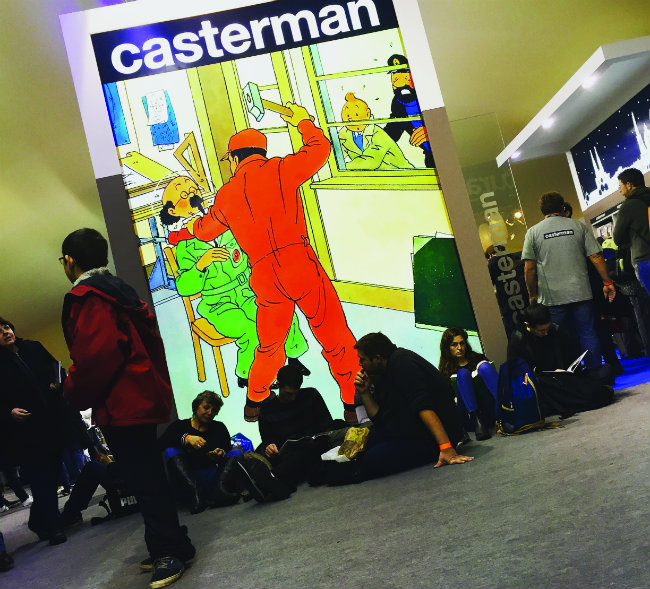

Billions of blue blistering barnacles! There’s a lady dressed up as Tintin. Sporting a mousy quiff, she’s wearing plus fours, white socks and a light blue jumper. Where’s her trusty little dog, though? Snowy must have been left at home. On the streets of Angoulême, everyone else is out in force. This Charente city is full to bursting: nearly a quarter of a million fans are in town for the annual comic book festival – Le Festival International de la Bande Dessinée or FIBD.

They’re all showing signs of comic book fever. In nearly all the shop and café windows are images and figurines of famous comic book characters. Building walls are daubed with huge, colourful murals. At more than 20 different sites across town there are exhibitions, lectures, workshops, films, book markets and author signings. One of the larger venues is an enormous canvas pavilion built over an entire city square, with hundreds of comic book publishers displaying their wares inside. Outside, despite the January rain, thousands of fans are queuing to get in. Once through the doors (and the security checks) they’re squashed up to 30 deep in an attempt to get their precious books signed by the authors.

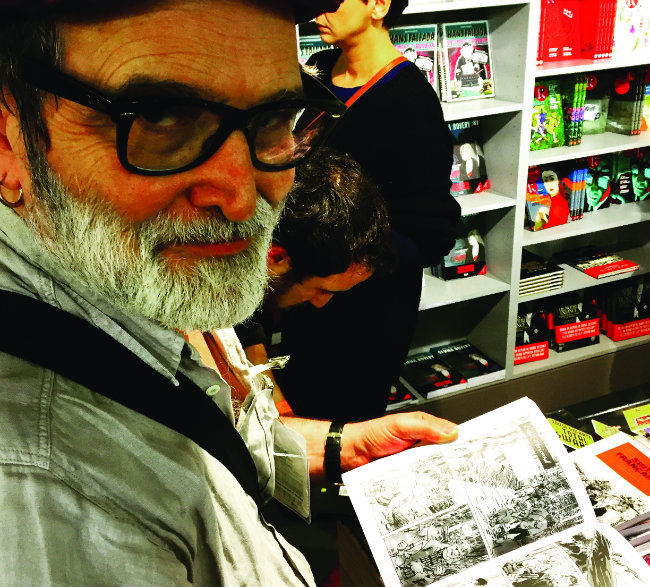

Stephen Collins, the British author of The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil. Photo: Dominic Bliss

A Bande Apart

Comic books, or bandes dessinées (BDs), as they’re known, are big business in France. Huge business, in fact. According to the magazine consoGlobe, at least 15 new titles are published every day; over 5,500 a year. During the course of a year around 36 million comic books are sold altogether. Translations of Japanese manga comics are enormously popular, as are the flimsier comics, especially the American superhero ones. Recent years have seen the growth of what’s known as graphic novels – normally hardback, highbrow and high-priced. But most popular of all are what’s known as the Franco-Belgian comic books.

The latter have been perennial favourites for us Brits, too: Tintin, Asterix, Lucky Luke, The Smurfs (aka Les Schtroumpfs), Blake and Mortimer… kids of a certain generation on this side of the English Channel grew up to love many of these characters.

In France they call comic books the ninth art (the first eight being architecture, sculpture, painting, dance, music, poetry, cinema and TV). Culturally they are considered far more important than they are in the UK. In Angoulême, for example, enormous amounts of state funding have been used to build the very impressive Cité Internationale de la Bande Dessinée et de l’Image with its museum, library, bookshop and cinema. According to the Association des Critiques et Journalistes de Bande Dessinée, as well as the annual Angoulême festival, there is at least one smaller comic book festival staged every month in France throughout the year.

One of many comic-style murals that adorn the streets of Angoulême. Photo: Dominic Bliss

Forbidden Fruit

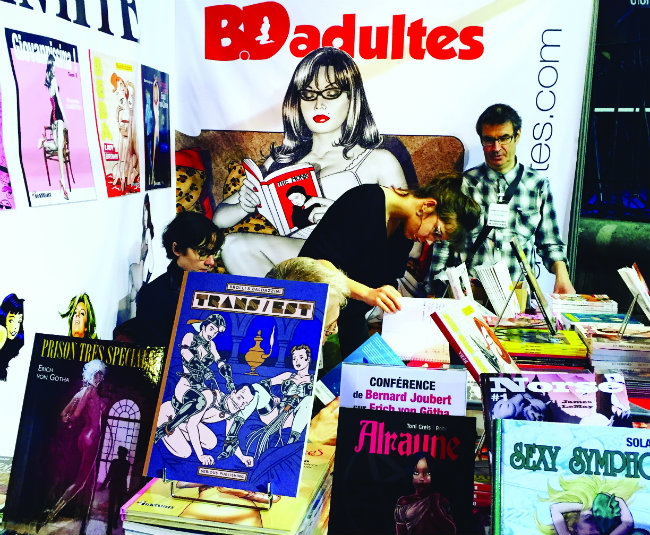

To get an anecdotal indication of the medium’s impact, just walk into any French hypermarket and head for the book section. There will be at least one long row dedicated to BDs, with readers both young and grown-up happily rifling through the thousands of tomes on offer. The subject matter is always mind-boggling in its diversity: adventure, fantasy, crime, gothic, sci-fi, war, superheroes, cartoons, even some astonishingly graphic pornography (yes, just metres away from the fruit stall!). Unlike in the English-speaking world, in France it’s perfectly normal for grown men – and they are usually men – to read comic books on public transport, just as they would a traditional novel (although fellow passengers may baulk at the porn).

Comics first established themselves within France’s literary culture in the early 20th century, initially as comic strips in newspapers. It was American cartoon character Mickey Mouse, however, who was the catalyst. In 1934 the owner of a huge French syndication bureau bought the rights from an American publisher to comic book stories featuring the loveable rodent and other Disney characters. He then launched a French-language children’s magazine called Le Journal de Mickey (still published today). Across France and Belgium there quickly followed a whole raft of children’s comic books based on American characters. Sales went stratospheric.

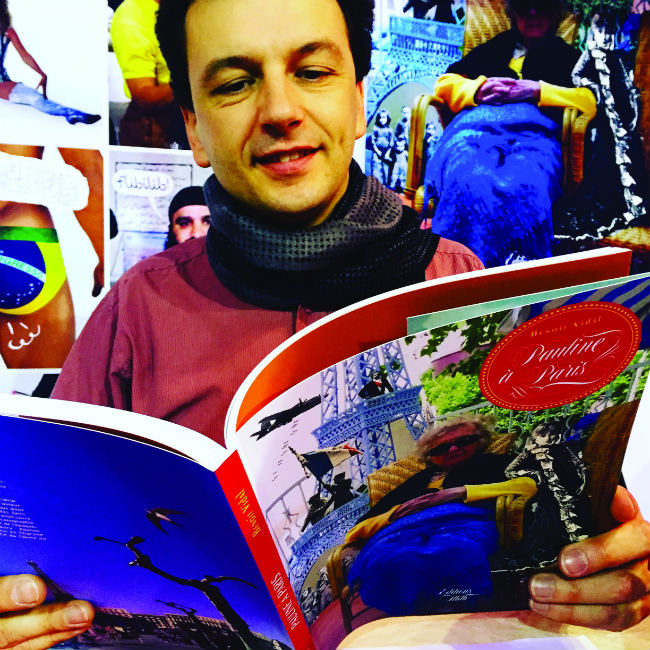

Benoit Vidal signs a copy of his comic Pauline à Paris, which features his grandmother. Photo: Dominic Bliss

Then, with the Second World War and the German invasion, the import of American comics into France and Belgium was duly banned. Into the ensuing vacuum stepped dozens of young authors and artists who created their own home-grown characters. Over the following years, all the most recognisable Franco-Belgian characters came to life: Tintin, Astérix, Les Schtroumpfs, Spirou et Fantasio, Blake et Mortimer. It was the golden age of bandes dessinées.

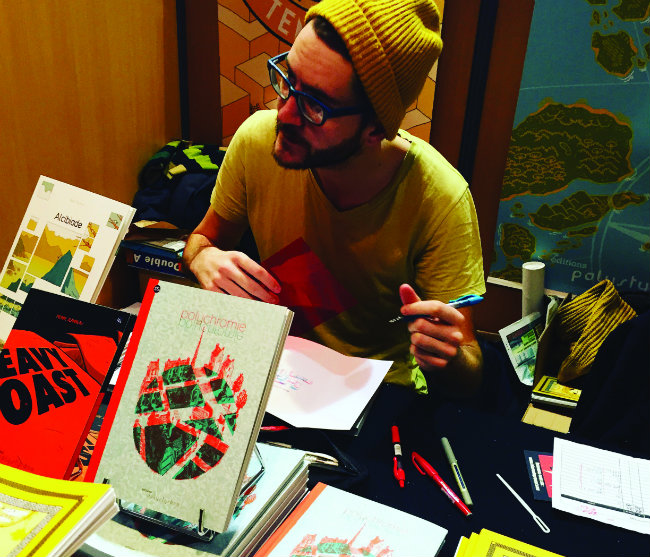

Back in Angoulême, it feels like comic books are entering their second golden age. In the cavernous marquees dotted around town, hundreds of publishers are flogging their books to the public, luring in fans with author signings. The variety of subject matter is astounding. Lots of children’s cartoons. Whole stalls dedicated to highbrow graphic novels in multiple European languages. A Swiss publisher has produced a comic book version of the William Tell legend. A Swedish publisher is offering a biography of pop band Abba next to a comic book tribute to Stieg Larsson, author of the Millennium trilogy. There’s a Norwegian biography of Edvard Munch. There are superheroes, detective stories, fantasy, LGBT, lots of Nordic noir, plenty of surreal stuff, plus the inevitable porn.

adult comic books are popular in France, openly dealing with sexual themes and graphic by nature. Photo: Dominic Bliss

In Angoulême’s Chamber of Commerce, Nicolas Pagnol, grandson of the famous writer and filmmaker Marcel Pagnol, is promoting comic book versions of his grandfather’s works. Three have already been published, with 12 more due by 2020, including La Gloire de mon Père, Le Château de ma Mère, Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources, all of which were adapted for cinema in the 1980s and 1990s.

“Marcel’s works are very cinematographic, so they totally lend themselves to comic book adaptation,” Nicolas says. “It’s another way of putting them on a stage.”

He hopes the comic books will inject new popularity into the writings. “My goal is to get my grandfather’s work discovered by a new generation, but also to help those who already know his work from a long time ago to rediscover it. The younger generation read fewer and fewer novels nowadays. This is a way of introducing them to a new universe. Say 100 youngsters read the comic books, then perhaps ten of those go on to read my grandfather’s books. It’s a stepping stone.”

An array of comic books and comic book memorabilia. Photo: Dominic Bliss

A Thousand Words

Nearby, seasoned comic book author Emmanuel Moynot is promoting his new adaptation of the Irène Némirovsky novel Suite Française. Asked why Anglophones are so much slower than Francophones to appreciate the literary importance of comic books, he talks about a bias in favour of the written word. “This is a serious mistake,” says Moynot. “Ideas come before words. Words, just like pictures, should serve ideas. Literature and writing is not the only means of expressing ideas. In certain cases they are even insufficient. Writers are held back because they can’t draw. They’re obliged to describe instead, and that’s a weakness.”

Angoulême is a living, breathing comic book, covered in beautifully rendered murals. Photo: Dominic Bliss

The throngs of spectators at Angoulême’s main theatre have no trouble appreciating the cultural significance of the ninth art. Crammed into the main auditorium, they are watching enthralled as artist Fabian Nury demonstrates how he illustrates for Silas Corey, a series of comic books in the detective genre. The tricks of his trade are being projected onto a large screen above the stage.

In a much smaller venue visitors shuffle shoulder to shoulder through an exhibition of comic book art about rock music. There are BD versions of the Beatles, the Sex Pistols, the Who and Lemmy, all of which the fans peer at studiously. Nearby, in the Place des Halles, a comic book retailer from La Rochelle called Mille Sabords! (a Captain Haddock catchphrase from the Tintin books) has set up a stall selling all things Hergé. There are the comic books, of course, but also official games, stationery, accessories and hundreds of figurines. Among his treasures, displayed at the back of the stall, well beyond the grubby fingers of your average Tintin fan, are antique editions of Hergé’s masterpieces. Collectors gaze fondly, some of them on the point of drooling. These are the comic book equivalents of William Shakespeare’s First Folio, and their price tags prove just how the ninth art is venerated in France. There’s a 1930 original edition of Tintin au Pays des Soviets priced at 20,000 euros. Behind it, even further out of reach, is a 1948 version of Tintin au Congo for 35,000 euros. Billions of blue blistering barnacles indeed.

Emmanuel Moynot, author and illustrator of Suite Française, the story by Irène Némirovsky. Photo: Dominic Bliss

Sidebar: Franco-Belgian comics

Many of the world’s most famous comic book characters were invented by French and Belgian authors. Here are the main classics…

Tintin

With his trademark quiff, plus fours and sidekick dog Milou (Snowy, in English), Belgian reporter Tintin travelled the globe on a series of picaresque adventures accompanied by the likes of the hard-drinking Capitaine Haddock, the infuriatingly deaf and scatty Professeur Tournesol (Professor Calculus) and the ever-incompetent detectives Dupond et Dupont (Thomson and Thompson). Created by Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, writing under the pen name of Hergé, Les Aventures de Tintin have been translated into more than 70 languages, and sold well over 200 million copies worldwide.

Astérix

Astérix was the smart little one with a huge moustache. Obélix was the big fat one with pigtails, a menhir stone and pet terrier, Dogmatix. Together, from their ancient Gaulish village, and with the help of a magic potion, they were able to resist the military might of the Roman Empire. The majority of the 36 books, which have sold more than 325 million copies worldwide, were written and illustrated by French duo René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo. This makes them the country’s most significant literary export.

Astérix. Photo: Dominic Bliss

Les Schtroumpfs

Tiny, blue-skinned and always sporting Phrygian caps, Les Schtroumpfs (The Smurfs) lived in mushroom-shaped houses deep in the forest. Their adventures featured across 30 original comic books by Belgian artist and author Peyo (Pierre Culliford). But the franchise has since grown to include successful films, TV series, video games, theme parks and figurines.

Lucky Luke

Comedy western Lucky Luke was the brainchild of Belgian cartoonist Morris (Maurice De Bevere). It features the titular hero who famously shoots faster than his own shadow and, accompanied by his trusty horse Jolly Jumper and dim-witted dog Rantanplan, patrols the Wild West capturing gangsters and righting wrongs. There are close to 70 albums in the series, the best written by René Goscinny of Astérix fame.

Blake et Mortimer

Starring Sir Francis Blake, an MI5 spy, Philip Mortimer, a British scientist, and the villain Colonel Olrik, this series of more than 20 comic books mixes detective work, espionage, science fiction and fantasy, all illustrated in the ligne claire style that Hergé pioneered with Tintin. The first 11 albums were written and illustrated by the Belgian series creator Edgar P. Jacobs, with others taking over after his death in 1987.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY