Summer in the Vercors

Life happens in cycles. Winter brings snow and hardy cover crops. Summer sings of rich produce and lazy afternoons. This natural cycle sets the rhythm for many farms in the Vercors mountains, where organic agriculture holds a prized place. Summer has traditionally been the harvest season, and the long days mean more time to discover a sunnier side of the mountains, where the air is warm, just like the welcome.

The Vercors, a limestone citadel on the fringe of the French Alps, straddles the Isère and Drôme départements. On a summer day, the smell of pine permeates the air in the Quatre Montagnes region. Farther south, the Diois area dissolves into Provence with lavender and sunflower fields. Dotting the entire plateau, mustard-yellow signs all along the roads direct visitors to one or another of the 49 Fermes du Vercors. One such sign, in the Isère southwest of Grenoble, led me to La Ferme du Clos.

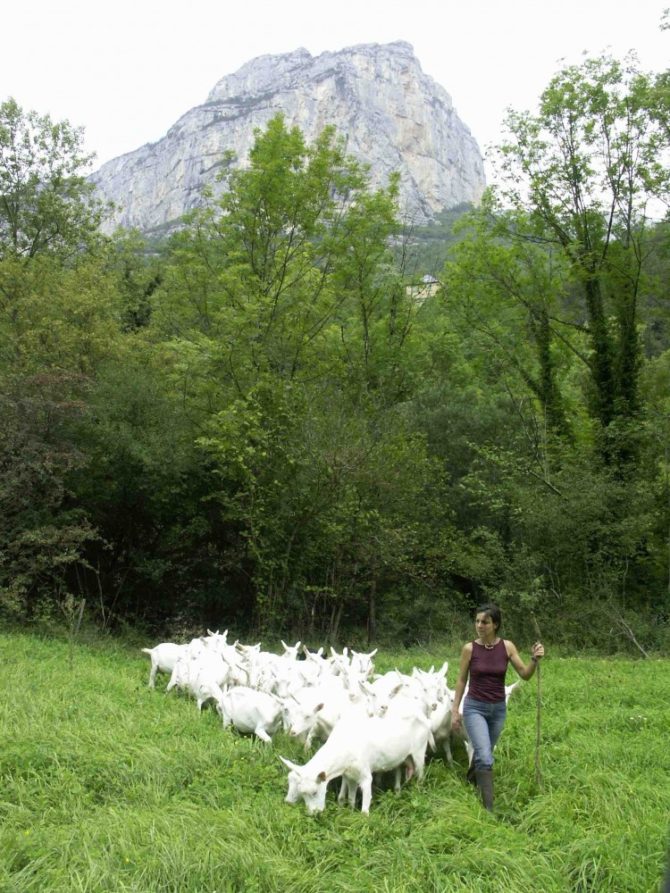

That’s where Angélique Doucet spends her days tending 35 white Saanen goats, running a bed-and-breakfast, harvesting walnuts, welcoming school groups, hosting concerts, housing the occasional writer, even feeding guests with organic goods from her farm. Wow! Even with all that she still overflows with energy, a genuine smile and a solid ecological streak. Her farm is strictly organic—or bio, (pronounced bee-o), as the French label all things biologically correct.

“I don’t use any antibiotic treatments on my goats. I prefer to prevent problems by making sure the goats eat well, avoid stress and grow strong on their mother’s milk,” she explains as her charges ruminate organic hay at their own speed. All of Doucet’s guests get a chance to follow her into the barn or the field to sample organic farming life. In the summer she even finds time to organize full- and half-day farm visits for groups. If you have never milked a goat, here’s your chance. No need to fear. After all, even Angélique worked as an accountant until seven years ago, and she does a fine job.

One treehouse, one yurt

Farther south, on the way to La Ferme du Pescher in the Drôme, the thick spruce forests of the Isère gradually give way to a few maritime pines. Beige stone houses with terra-cotta roofs begin to punctuate the landscape, replacing the steely schist roofs farther north. The just-setting sun stains the small homes in ochre and orange hues, reminiscent of the tales of Marcel Pagnol.

Florence Réty runs the Ferme du Pescher, in the Parc Naturel Régional du Vercors, with her companion Olivier Hutter and a small crew of cohorts. It can’t be an easy job. Besides looking after some 50 goats and growing all sorts of fruits and vegetables, the family oversees their guests’ well-being. I can’t help but think how lucky their little girl Juliette is. Right in her own backyard, she has one yurt imported directly from Mongolia, a small chalet, a high-flying treehouse, and two gypsy-caravan wagons. At her age, I would have traded an entire herd of My Little Ponies for a real yurt and a cabin in the treetops. But then again, my backyard hardly measured the 200 acres hers does.

Réty confirms that the farm life is far from idyllic. “You have to find outlets for your products, and there’s always more work to do, between receiving guests, harvesting, milking and selling. We start early and finish late. But at the same time, we’re independent, and we get to work outdoors.”

The other members of the Ferme du Pescher community each have their own role—Olivier Schlosser sells produce at local markets, Dao and Franck Fayolles create pottery and run a small Franco-Thai eatery. Not far from La Ferme du Pescher, visitors can enjoy the outdoors in a more leisurely fashion. Sturdy hiking legs and a supply of trail mix may be required to conquer the plateau d’Ambel, which easily offers an afternoon’s worth of exploring. Over the course of the five-hour trek, little yellow flowers illuminate the expansive fields like an earthly star system. A chamois darts away at the sound of human intruders. Paragliders dot the sky above as they harness the warm mountain air with their bright sails—they seem so peaceful, just floating in the cloudless summer sky.

Living up to the label

Back at the farm, I ask Florence and Olivier why they chose organic farming, which seems more difficult than conventional agriculture. “Being bio isn’t a constraint,” says Florence, “but it requires a lot of investment. We never considered doing anything but organic farming. It just seemed logical and in the Drôme, the people were paying careful attention to organic products long before it became so trendy.” It’s true; this département leads the country, with some 130 certified organic farmers.

At La Ferme du Pescher, a rustic cabin serves as a shop where guests can purchase farm-fresh produce. A small, unmanned money box replaces the beep-and-scan cash register; prices are posted and each guest is trusted to pay for what they take. And when nature calls, there is even a log outhouse with a composting toilet. No one ever said going organic was a picnic.

In fact, going organic can be quite a challenge for France’s farmers. The French AB label—Agriculture Biologique—bans genetically modified organisms. It forbids giving animals anything but organic feed. Farmers must rely on preventive measures like working with breeds adapted to their areas, avoiding overcrowding the land and limiting any kind of treatments to the strict minimum. Inspectors pay visits at least once a year from the time farmers declare their intention to work organically. After a two-to-three year conversion period, the soils and animals can finally be declared pure enough to be certified for the AB label.

Petting the porkers

At the Ferme des Colibris in Méaudre, back in the Isère not far from Grenoble, Eric Rochas comes out to shake my hand, a blade of straw tucked between his teeth—it’s quite likely his great-grandfather greeted guests to the farm the same way more than a hundred years ago. This farm’s products have been wearing the AB label for a dozen years, but chemical products were never ever a part of its system.

“A farmer is someone who feeds others,” explains Rochas, “and we just couldn’t see ourselves poisoning people. We respect them.” His 220 cows and pigs can be seen grazing on the mountain grass, or lazing around contentedly. A few calves frolic about. Everything looks pastoral, as a farm should.

It can, however, feel a bit weird petting the pink little porkers, then stopping at the farm’s shop to buy a slab of bacon. Most of us are used to getting our meat from a freezer, not a field. We know beef comes from cows, but we never actually see the cows. I felt comforted knowing the animals had been raised with care, had a good life and had always been in good hands. Rochas treats his animals respectfully, not just as meat in the making. It’s that respect for life—be it plant, animal or human—that pushes these farmers to leave the chemicals behind and adopt a more natural way of working. Their products and their farms are all the healthier for it.

Bikes and blue cheese

Visitors can keep in shape, and leave less of a carbon footprint on the lush landscapes as well. Since the Vercors is a plateau, cycling around is a feasible option. Sure, some routes climb and drop, but a little effort does a body good, and a little biking does the planet less harm. With the breeze caressing your cheeks and the ribbon of road under your tires, a bike trip around the Vercors can be a wonderful way to experience the landscape from one farm to another, and it’s not necessarily a long-distance affair.

Cycling north just seven miles from the Ferme des Colibris to the Coopérative Vercors Lait, I meet Philippe Guillioud, who runs the enterprise. In his closet-sized office, posters from past Fêtes du Bleu du Vercors-Sassenage festivals decorate the white walls. A cheese basket holds a dozen pens and one Opinel knife. On the door of one of the cheese chambers, a big red sticker reads Le client? L’homme le plus important de notre entreprise. This former rugby player comes with a heart as solid as his sturdy frame.

“I know every one of the farmers who supplies us with milk. There’s a human connection in this cooperative and our objective is to put mankind at the heart of what we do,” says Guillioud. The cooperative plays a real social, economic and cultural role in the Vercors, uniting some 60 stockbreeders. Five of them raise their cows organically, and by the end of this year that number will have nearly doubled, thanks to the cooperative’s support. Without it, many Vercors dairy farmers simply couldn’t afford to stay in business.

Customers can shop at the source at the cooperative. Organic or not, all of their cheeses are hand molded, aged and packaged on site before being arranged in the little shop’s display cases. One bite into a chunk of the local blue cheese, AOP Bleu du Vercors-Sassenage, and you can taste what the French mean when they talk about terroir—definitely something worth celebrating!

Every August since 2001, the Parc Naturel Régional du Vercors and the Syndicat Interprofessionnel du Bleu du Vercors-Sassenage have hosted their annual Fête du Bleu du Vercors-Sassenage. The festivities include cooking classes based on local products, agricultural competitions and demonstrations on how the celebrated cheese is made.

For a healthy dose of terroir of all sorts, Les Fermes du Vercors invite guests to visit their farms and see first-hand where the food comes from. What could be a better reward after a day of hiking or biking? Many farmers even offer you the chance to stay on-site and get your hands a little dirty. Then the cycle comes full circle and with it, time to say au revoir as summer in the mountains fades into fall.

VERCORS NOTEBOOK

La Ferme du Clos Angélique Doucet opens her home to guests with rooms starting at €55 per night, breakfast included. Guests can also enjoy farm meals for €18, drinks included. Le Clos, Châtelus, 04.76.36.10.94. [email protected]

La Ferme du Pescher Guests can sleep in a Mongolian yurt, a tepee or a small chalet, starting at €30 per night. There are many nature trails in the area, so bring comfortable shoes. Le Pescher du Bas, Omblèze, 04.75.42.93.18. www.lafermedupescher.com, [email protected].

La Ferme des Colibris Customers can buy the farm’s fresh beef and pork products, and farmer Eric Rochas is happy to take you into the barn or field to meet his herd. Les Arnauds, Méaudre, 04.76.94.29.18. [email protected]

Coopérative Vercors Lait The cooperative’s shop sells cheese made with milk from Vercors farmers—several are organic—as well as quality products from a few farms in other Alpine areas. Route des Jarrands, Villard de Lans, 04.76.95.33.21. www.vercorslait.com

For more information on all of the Vercors farms, www.apapvercors.com (in French only)

Originally published in the June 2012 issue of France Today

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *