Pays Basque: The Gourmet Trail

Enigmatic and welcoming — the Basque Country is both. Basques are very proud of the particularities they’ve managed to hold onto in the face of constant adversity. Their admirable strength of character has enabled them to preserve both their unique language — it has no known roots or relatives — and their vibrant traditions, which are far from hokey folklore. They pay no attention to the border on either side of the Pyrenees. They cross back and forth without thinking, even for just a meal — they’ll lunch in Spain and dine in France, or vice versa, depending which side they reside.

Washed by the Atlantic Ocean and protected by the mountains, the Basque region has a humid climate, with luxuriant green grass and mild temperatures. It’s unmistakably Basque, recognizable at first glance by its whitewashed houses with doors and shutters painted red or green, the colors of their flag. And, like so much else about the Pays Basque, the cuisine is also unique — and rich, thanks to the generosity of nature and the culinary talents of its people. Fish, ham, charcuterie, poultry, cheese, pastry, chocolate, confiture, cider, wine, spirits and even peppers are proffered in abundance to the greedy visiting gourmet.

Basque country, France. Photo: Flickr, JPC24M (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Although the largest part of the Basque country lies in Spain, the French Pays Basque to the north is worth a journey all its own. Dating to the French Revolution, the ancient Basque provinces—Labour, Soule and Basse Navarre (once a part of the powerful kingdom of Navarre attached to France on Henri IV’s accession to the throne in the late 16th century)—became the modern département of Pyrénées Atlantiques. It extends inland from the rugged Atlantic coastline, its towering surfers’ waves alternating with estuaries of calm, to a pastoral landscape of low mountains and rounded hills dotted with cattle and sheep, then on into deeply carved valleys and finally to summits more than 6,500 feet high.

Everywhere the presence of man has fashioned the land, and its many villages are very lively. On or near virtually every town square, there’s a court called a fronton with one tall wall for the traditional game of pelote (the Spanish pelota, also called jai alai), which can be played in several different ways. In the most spectacular variation, players use a chistéra, a curved scoop woven of reeds, to catch and throw the ball, the pelote, whose speed can reach more than 180 miles an hour.

Hôtel du Palais. Image: Flickr, Dennis Jarvis (CC BY-SA 2.0)

During the 19th century industry and mining operations were in full swing on the Spanish side of the border, enriching the region. On the French side, it was seaside tourism that developed, thanks to the Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III. Born to an aristocratic family in Granada, Eugénie de Montijo had spent summers with her parents in Biarritz, and her continuing presence there launched the city as a resort. Her husband the emperor had a grand villa built on the water; it would later become the Hôtel du Palais.

Let’s begin, then, with Biarritz, the “European Surf Capital”, an elegant, worldly city full of villas and other buildings with wildly fanciful architecture, a long way from the simple little whaling port of yore. Since Eugénie’s day the city has continued to enchant all comers, including more than a fair share of artists and celebrities. Even today, suntans are still chic here, and hair is streaked by salt and sun, soaked up on the three main beaches where the city meets the sea.

Biarritz, Grande Plage. Image: Flickr, Fred Romero (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Bordering the Grande Plage, the restored Casino is an Art Deco marvel, and farther along, past the old fishing port, the statue of the Virgin atop the promontory rock called the Rocher de la Vierge has become the city’s unofficial symbol. As for food specialties, the complete array of Basque gourmet products can be found at Arostéguy, the fine grocery that’s a meeting place for everyone in town (see sidebar). The Maison Paries pastry shop is also worth a special detour. Everything on offer here is excellent, but the specialty is the mouchou, from the Basque word musu, for kiss — a little round almond cake with a crisp crust and a soft interior.

From Biarritz, follow the coast to Saint-Jean-de-Luz, a little town and fishing port whose douceur de vivre is legendary. It’s every bit as chic as Biarritz while much less extroverted, and it’s renowned for its glorious history, most notable for the marriage of Louis XIV to Maria Theresa, the Infanta of Spain, celebrated in the church of Saint Jean Baptiste in 1660. It’s worth making the effort to attend 8:30 am Mass there today, to hear the haunting Basque hymns.

Saint-Jean-de-Luc. Image: Flickr, Pablo Sanxiao (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The town is small, so you can walk everywhere without getting lost. Facing one another diagonally across the port are the houses in which the royal couple stayed the night before the wedding: the Maison Louis XIV, with its short twin towers, and the Italianate Maison de l’Infante, looking much like a Venetian palazzo. You must taste the famous almond macaroons from the pastry shop Adam; invented for the famous marriage, the recipe has never been changed and still remains a secret.

Another local specialty, battili, is a salted tuna filet, line-caught, smoked and dried—a method of preserving tuna that is practically obsolete. Its flavor is subtle, and it’s served thinly sliced with an aperitif, or on toasted bread drizzled with a little olive oil and rubbed with fresh tomato. You’ll find battili and many other seafood specialties at Batteleku, across the Nivelle River from Saint-Jean in Ciboure.

La Rhune. Photo: Wikipedia,Daniel VILLAFRUELA (CC BY-SA 4.0)

After leaving the coast on the way to Ascain, there’s a pleasant stop to make at the artisanal cider mill Txopinondo—the only one on the French side of the border that makes typical Basque cidre. It takes a little skill to fill your glass directly from the cask, as tradition dictates, but it’s worth a try. The pretty village of Ascain is the departure point for a little train excursion to the 3,000-foot summit of La Rhune, the emblematic Basque mountain that marks the Spanish frontier, where you’re likely to see vultures and pottocks, small, semi-wild horses known for their sweet temperament.

Red hot

Espelette is known far beyond the Basque country for its hot piment (pepper), which was granted AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée) status ten years ago. After the autumn harvest the peppers, strung into garlands, are draped on facades and shutters to dry, gradually fading from bright red to a darker shade. They are then dried in an oven before being ground into powder. In the local cuisine piment d’Espelette replaces black pepper. Made into a purée it is used as mustard and as a gelée it’s perfect with game terrine or fromage de brebis (sheep’s cheese). Everyone in the village sells it; a favorite producer, Vincent Darritchon, is located outside the town.

The town of Espelette. Photo: Flickr, dynamosquito (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Orchards around the village of Itxassou produce two famous varieties of black cherries: the Peola, for baking in cakes or turning into traditional confiture; and the Beltxa, usually served with fromage de brebis. Visiting the orchards, you can also admire the landscape of the Pas de Roland, where, according to legend, a rock was pierced by the horseshoe of the steed ridden by Roland, the nephew of Charlemagne and heroic knight of the 11th/12th-century epic poem La Chanson de Roland, which describes how he was ambushed and killed while crossing the Pyrenees by avenging Vascons, or Basques.

The Nive Valley

Heading for Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, you can make a short loop through Ossès for a visit to the fattened ducks raised on the Arnabar farm. Their foie gras, magrets and confits are very much in demand, as are their prepared dishes including aoxa de canard, a ragout of duck instead of the more traditional aoxa of veal.

Irouléguy vineyard. Photo: Wikipedia, Vignoble du Sud-Ouest (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Irouléguy is known for its eponymous wine. The vines, grown in terraced vineyards, were planted in the Middle Ages by monks to supply wine for pilgrims traveling to the shrine of Saint Jacques de Compostelle (Santiago de Compostela); for centuries the wine was very rough and only consumed locally. But great progress has been made, and now Irouléguy has obtained an AOC designation, one of the smallest winegrowing districts in the country to do so.

Among the very best of the Irouléguy producers is the Brana family, based in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, which is principally famous for its fruit-based digestifs. Etienne, the third generation of this family of wine merchants, decided to create a traditional distillery with copper alembics nearly 40 years ago, and to use the renowned poires William—better known in the US as Bartletts—from his own orchard to make clear pear brandy. Today connoisseurs consider Poire Brana the best in the world.

Brana also distills prune (plum), raspberry, quince and other fruit liqueurs. Today his daughter Martine carries on the digestif business, while her brother Jean runs their AOC Irouléguy vineyard created 20 years ago. The company was the first to start making white Irouléguy again after its production had been abandoned.

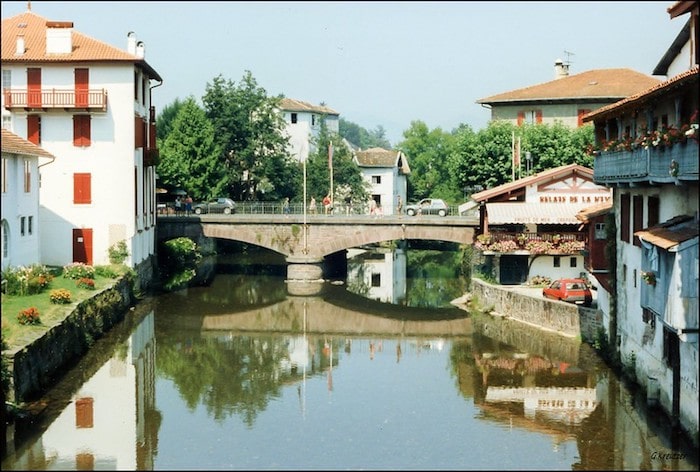

Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. Photo: Flickr, GK Sens-Yonne (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port on the banks of the river Nive, with its pont pavé and its pink sandstone tower, its well preserved Old Town and its UNESCO-classified Porte Saint Jacques, is a place of great serenity—perhaps because of the passage of all those prayerful pilgrims on their way to Saint Jacques de Compostelle. The pilgrims have been welcomed here since the Middle Ages, since this was the last stop before the climb to the Spanish border in the Pyrenees. The Saint Jacques tradition has been revived in recent years, and pilgrims are again passing through town.

Pilgrims on the gourmet trail head straight to the Maison Barbier-Millox, for one of the finest gâteaux basques anywhere, plain or with black cherries. This pâtisserie is also renowned for its chaumontais, a light meringue with cream and praline butter, a favorite dessert of Charles de Gaulle. In the neighboring village of Saint-Michel, the dairy of Les Bergers de Saint-Michel makes famous pressed, uncooked sheep cheeses—the best known is the raw-milk AOC Ossau Iraty, but don’t forget to also try the Arrodoy tommette.

Prize pigs

View of the Aldudes valley. Photo: Wikipedia, Harrieta171 (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Taking the time to climb to Les Aldudes is another must. Along the way you’ll see some superb mountain landscapes, and your reward at the top of the switchback route is the salaisons (salt-cured meats) of Pierre Oteiza. They are made from Basque pigs, a race once threatened with extinction. In 1987 there were only 27 pigs known to exist, on 15 farms; in 2009 there were 5,000 animals on 80 farms. Oteiza is responsible for the reappearance of these free-range pigs whose meat is so delicious. The climb up to him is worth making, but if Les Aldudes seems too far, you’ll find his products in other local stores too.

Heading toward Bayonne, the gourmet trail must pass through Hasparren, for the hams of Louis Ospital. His son Eric is now in charge, making fine old-style charcuterie found on Michelin-starred tables all over France, along with his equally prized fresh pork.

At Bayonne the Nive and the Adour rivers join to form an estuary that flows into the Atlantic. The port city has conserved all its beauty—ancient houses, quays, churches, châteaux, the citadel, museums, including the Musée Basque—the whole city, a joyous place where everyone seems to always be in a good mood, deserves a lengthy visit. Famous for its annual, weeklong Fêtes de Bayonne in early August—with traditional Basque music, outdoor dances, corridas, parades and fireworks—it’s also known for ham and chocolate.

Four hundred years ago, the Portuguese Jews who fled the Spanish Inquisition and settled in Bayonne were skilled in the art of grinding cacao—at that time, chocolate was only consumed as a drink. Eventually the powdered cocoa became a specialty of the city and chocolateries prospered, but mechanization eventually pushed them out of business. Only seven chocolatiers remain, and the most interesting is a young Japanese woman, Yumiko Morel, working in the adjacent community of Anglet.

But much more than with chocolate, Bayonne is synonymous with ham. For a long time the celebrated jambon de Bayonne did not have a protected appellation; it was made anywhere, and rarely made correctly. With the creation of both an IGF (Indication Géographique Protégée) and a consortium, that problem has been corrected. To make true jambon de Bayonne, fresh hams are rubbed and covered with salt from the Adour Basin, then put into a salting-tub. After several days they are washed to remove the excess salt, and sometimes pressed if they are too wet. Finally, the hams are hung in a curing room, where they lose some of their weight and slowly dry—it takes from nine to twelve months to cure a Bayonne ham. Besides the savoir-faire, unquantifiable aspects including air and wind play an important role in the flavor of the hams during the curing process. Whether regulated by hand or by computer, it’s essential to have air circulating around the hams. Small producers depend on natural drafts, so their windows remain open to the prevailing winds. To verify the authenticity of a ham, look for the Lauburu, the Basque cross, marked on the rind with a branding iron. Two high-quality firms to visit are Pierre Ibaïalde and Maison Montauzer.

Salt on a wooden spoon. Photo: Unsplash, wjtuinstra

From the France Today archives

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email