Willy Ronis: The Master’s Moment

Willy Ronis passed away on September 12, 2009, at the age of 99.

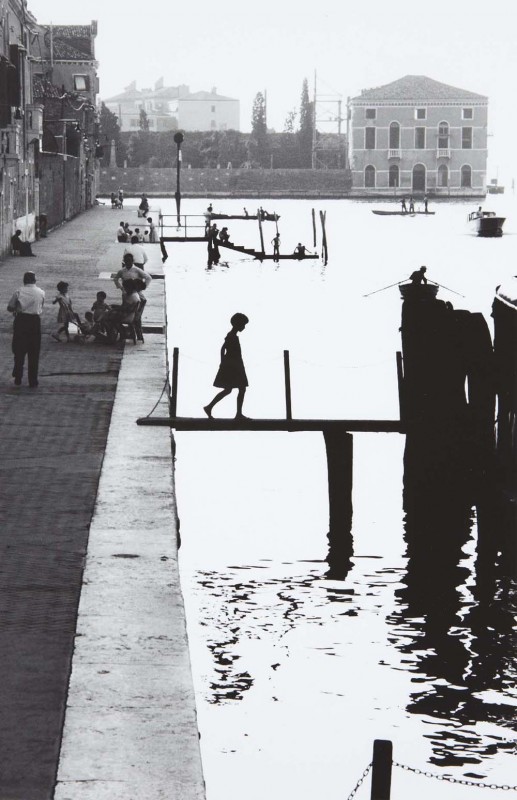

The last grand master of “humanist photography” has his season in the sun.

He’s the last of the giants. Edourd Boubat is dead. Robert Doisneau is gone. His friend Henri Cartier-Bresson died last year. Of this select group of photographic geniuses, only Willy Ronis remains, and this is his year. He is ubiquitous. He’s the star of the biggest exhibition of the year, Willy Ronis à Paris, held at City Hall. A year ago his name was known mostly to the older generation of collectors; today he’s celebrated as a national treasure. The Taschen library in St-Germain-des-Prés was mobbed when he came in to sign his latest book. A vintage print of his most famous photo, Nu Provençal, just sold for €25,000. The Camera Obscura gallery is exhibiting his early work.

Life is good for Willy Ronis, yet he remains unaffected by it all. “It would not be elegant to say I don’t care,” he says, his ironic eyes looking over his reading glasses, “but it’s happening a little late. In 1960, I had accomplished most of my work. If I had died then, the judgment of my work would be no different today.”

“Golden nuggets”

The photographer, who has taken more than 90,000 pictures over 70 years, turned 95 this year and looks 20 years younger. His energy fills the room in his apartment on the top floor of a faceless building in his beloved 20th arrondissement. Cartier-Bresson roamed the world—he lived in Mexico, traveled around the United States, photographed China’s last days before the triumph of Mao. But Ronis’s territory has always been Paris, where he sought what he calls his “golden nuggets.” “My wife was not a sailor’s wife. My marriage would have fallen apart if I had been gone for long periods of time,” he says.

Ronis is inspired by the common people of Paris, anonymous faces in the crowd. “He photographs the happiness of simple people, the small moments of joy despite the difficulties of life,” explains Kathleen Grosset, whose father founded Rapho, the first modern photographic agency, even before Magnum. His images have entered our eyes and minds even if we don’t realize it: the couple kissing at the top of the Bastille with the view of Paris at their feet; the barge on the Seine with little children playing as if in a playground, the Académie Française reflected in the Quai Conti below.

“There’s a gentleness about him,” explains Peter Fetterman, the Santa Monica gallery owner who has represented Ronis in the United States for over 15 years. “Cartier-Bresson can be detached sometimes. Willy Ronis’s heart is in front of the camera. His work is deceptively simple.”

The master finds his milieu

Born on September 14, 1910, in the ninth arrondissement, Willy Ronis received his first camera, a Kodak 6.5×11, at 15. His father, who had fled the pogroms in the Ukraine (his mother came from Lithuania), was a studio photographer. “I was naturally interested in photography,” says Ronis, “but it was not my calling.” The young boy loved music and wanted to be a composer, but his mother forced him to train as a violin performer.

“I stopped playing forever when I was 22, when I had to start working,” he recalls. His father had been diagnosed with cancer and due to the hardships of the worldwide economic slump couldn’t afford to hire an assistant. For four years, Willy (he says he never knew where his first name came from) worked in the studio on Boulevard Voltaire. “I lived in depression for those four years,” he says. “I had a very deep love for my father, who was dying, and my daily life was a lie; I hated the kind of photography my father was doing.” When his father passed away, Ronis abandoned the studio to his many creditors.

Then his whole life changed. At the Société Française de Photographie, which organized an international photo show each year, Ronis discovered another type of photography—and had a revelation. “I had found something I was in harmony with,” he says of the work of Dorothea Lange and other Farm Security Administration photographers. So, between June 1936 and the outbreak of the war, Willy eked out a living for himself, his mother and his brother Georges. “Photography was a marriage of convenience at first. I had to survive.”

But that year Ronis met Cartier-Bresson. “He was exceptional,” he says. Robert Capa, the founder of Magnum, would become his great friend. “We were like night and day. He was a ladies’ man and made lots of money. I would go and see him often in his studio behind Montparnasse on rue Froidevaux,” Ronis recalls. “[Capa] was a visionary. One day, after I had gone to Yugoslavia and Greece, he had the idea of packaging the reportage, writing a headline that said ‘Our Reporter in the Troubled Balkans,’ and sending it to publications around Europe. I made a little money from it.”

An unusual reward

When the Germans invaded France, Ronis, who refused to wear the yellow star, left Paris. South of Tours, he found himself among a group that was spotted by the Germans. He was the sole survivor. His mother stayed behind in Paris, yet survived. “The concierge did not betray her,” he says, almost incredulous. After the war, the French railroads hired him to record the return of French prisoners. Ronis, who had joined the Rapho photo agency along with Doisneau and Brassaï, began prowling two neighborhoods in the northeast part of the capital. Their names would be the title of his most famous book, Belleville-Ménilmontant, published in 1954.

Perhaps because of his affectionate eye, Ronis’s work has brought an unusual reward: Many of the people in his famous photographs have come forward to meet him. Today he’s encountered 28 people he never thought he’d see again. “People I shot at random, all of a sudden I meet them years later,” he says. “It’s a wonderful present from life. It started happening in my 50’s, and some people have become real friends.” Like the little girl with the Phrygian hat in the photo Front Populaire, 14 Juillet (1936), or Riton and Marinette, from the 1957 shot Les Amoureux de la Bastille, who later ran Le Moderne Café and whom he met in 1988. Or Rose Zehner, a union woman he photographed during the strike at the Citroën plant in 1938. In 1980 Zehner, then 80 years old, wrote Ronis an open letter in the Communist daily L’Humanité. Finally, 44 years after the photo was taken, Willy and Rose met. The moment was recorded on film. So moved was he by the woman’s personality, Ronis wept.

Despite his success in the 1950s, Ronis experienced a fallow period in the 1960s and in 1972 decided to leave Paris for Provence, where he embarked on a teaching career. It was only after the unexpected success of his 1980 book, Sur le Fil du Hasard that Ronis returned to Paris. “In 2001, I decided I would stop taking photographs,” he says. “I had been doing that for 73 years and now I couldn’t walk, even with two canes. It was time to stop.”

Dider Brousse, owner of the Camera Obscura gallery and a student of Ronis, says: “The power of Willy Ronis lies in the fact that he’s not sentimental. But sometimes, for a very brief moment, there’s a flash of emotion triggered by the ephemeral nature of things. That’s what he has passed on to us.”

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email