French Film: Director Gilles Bourdos Discusses his Renoir Biopic

Over a year ago, on a frigid snowy winter evening in a French Alpine ski resort, a crowd of 200 festival-goers and local cinephiles attending the annual Festival de Cinéma Européen des Arcs, filed out of the world première of Renoir by writer-director Gilles Bourdos. Having basked in the film’s dazzling portrayal of light and languid summer heat, the audience marched outside without feeling the bitter cold, half expecting to hear the thrumming cicadas of the Côte d’Azur. We were nothing less than spellbound. Yet, little did any of us dream that this modest, €5 million-budget biopic on the twilight years of Pierre-Auguste Renoir would ultimately be chosen as France’s contender in the Best Foreign Language Film category of the Academy Awards 2014.

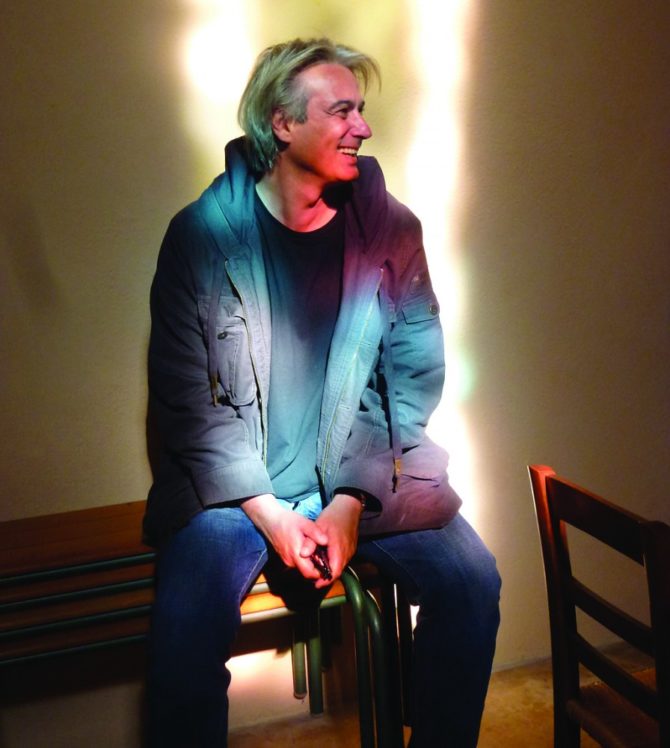

I caught up with Gilles Bourdos after that screening and we chatted about Renoir over tartiflette and local wine. Since that memorable evening, this sensuous biopic has quietly taken the world by storm, garnering enthusiastic praise around the world, and I’ve been fortunate enough to speak with Gilles several times.

In fact, the idea for Renoir came to the 50-year-old director, whose previous films include Inquiétudes (2003) and Afterwards (2008), almost by accident. When inspiration struck Gilles, who was born and raised in Nice and now lives in Brooklyn, he was wandering through his favourite New York City hangout, the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“When I entered the room of Renoir and Cézanne, I suddenly felt a rush of closeness for the French Mediterranean,” he remembers. “At first, I hesitated between the two artists, but also realized how different the subjects would be.”

Renoir opens with the striking image of a flame-haired girl bicycling down a tree-lined road in the south of France. Arriving at Renoir’s home, Des Collettes, which is situated in a hilly olive grove at Cagnes-sur-Mer, she pushes open the gate, strides through the garden and enters the artist’s studio unannounced, saying that she has come to pose for him.

Taken aback, the 74-year-old Renoir (Michel Bouquet) has no idea that this radiant, impudent teenager, Andrée Heuschling (Christa Theret), will soon become his final muse and inject his canvases with new energy and inspiration. “Her skin soaks up the light,” Renoir tells his entourage, a household of women servants who care for the ailing artist day and night.

At first, Dédée, as the girl calls herself, is unaccustomed to modelling and asks the painter if he minds whether she shifts her poses. “If I minded, I’d paint apples,” Renoir quips. “I need living, breathing material. What interests me is skin, the velvety texture of a young woman’s skin.” This remark is Gilles’ thinly disguised swipe at Cézanne.

“Cézanne was afraid of his models – he was a solitary man who shut out the world,” Gilles says. “Renoir was quite the opposite – he had a hot-blooded, down-to-earth, working-class side to him and a great appetite for life.”

What particularly interested Gilles was the cinematic opportunity to fully explore the artist’s little-known final years, between 1915 and his death in 1919, as he explains: “What I wanted to show in the film was Renoir’s celebration of desire and how the beauty of a young woman outweighs the loss of a wife, his illness and his constant worrying about his sons who are fighting in the war.

“Renoir’s arthritic hands had to be bandaged to hold a paintbrush and he’s confined to a wheelchair. But the more Renoir was gripped by those tenebrous forces and racked with pain, the more his paintings exploded with colours – flashy, candy-coloured oranges and reds that push away the negativity of the world.”

The destinies of Father and son become ineluctably entwined when Jean Renoir, a 21-year-old lieutenant, returns home to convalesce after suffering a serious leg injury in combat. As fate will have it, the artist’s filmmaker-to-be son (Vincent Rottiers) finds himself falling in love with Andrée.

Love on Screen

Jean and Andrée married in 1920, just a year after his Father’s death and he promised his ambitious bride to use his inheritance money to put her in the movies.

Changing her name to Catherine Hessling, Andrée (who was allegedly unremarkable as an actress) would star in five films directed by her husband before they split in 1931.

“She felt betrayed when Jean agreed, at his producer’s insistence, to give the star role to another actress in La Chienne (1931),” says Gilles, who was able to unearth a lone interview with Andrée from 1945, which saw her talk about how she was eventually forgotten by the cinema world. “Andrée died in 1979, the same year as Jean, and is buried in Thiais, near Paris, in a cemetery for the poor, homeless or disinherited. Her name is engraved on a simple tomb.”

Gilles says that French actress Christa Theret was a natural for the part of Andrée: “When Christa came to the casting call, she was a bit distracted and knew nothing about the film. Then she told me that her Father was an artist and her mother often posed for him as his model.”

For the film’s nude scenes, Gilles revealed that he was inspired by French artist and print-maker Pierre Bonnard’s photos of Marthe, his wife, walking naked in the garden.

“As for Vincent (Rottiers), I told him not to think too much about the great director, Jean Renoir, maker of the legendary La Grande Illusion (1937) and The Rules of the Game (1939),” says Gilles. “In this film, Jean is essentially a young man who has no idea of what he wants to do in life. He’s always been fascinated by his father and then, suddenly, he gets involved with a girl who is much more socially ambitious than he is.”

Capturing the Glow

Another major aim of the Niçois writer-director when making Renoir was to properly capture the sun-drenched glow of the Mediterranean on screen.

“Jean-Luc Godard did an admirable job of filming the southern landscapes in Pierrot le Fou (1965) and Le Mépris (1963) in the 1960s,” says Gilles, “but I can’t think of any French movie since that time which makes it look like some kind of Eden.

“I came to cinema by way of the visual arts, “unlike a lot of French filmmakers who began with a literary connection. As an adolescent growing up in Nice in an underprivileged neighbourhood, I was lucky to come into contact with the artists in the ‘New Realists’ gang, like the artist Ben or Robert Malaval. They had a strong influence on me.

“Perhaps because the Côte d’Azur is so close to Italy, I’ve always been more attracted to Italian directors like Bernardo Bertolucci, who is my mentor.”

Paradoxically, the luminous careers of Pierre-Auguste and Jean Renior had more than a young muse in common – the artist and his cinematic offspring were both reportedly somewhat bewildered by the avant-garde.

“In the 1960s, the French ‘New Wave’ directors named Jean Renoir as their ‘boss’, although he had a very mild interest in their filmmaking,” Gilles explains.

“In the same way, during Pierre-Auguste’s final years, a lot of young artists came to the Côte d’Azur to pay homage to le patron. He was very flattered but a bit suspicious, since he actually didn’t like their work all that much. ‘Why shouldn’t art be pretty?’ he once said. ‘There are enough unpleasant things in the world’.”

Transatlantic Success

Given the whopping success of Gilles’ Renoir in the United States, the film’s celebration of beauty and desire clearly struck a chord with a wide range of cinema-goers. In fact, there were just 40 cinema screening prints of the film made for the US market, but these were viewed by over 400,000 members of the public.

“In some ways, my film is the continuation of the almost magical love story between the Renoir family and America,” Gilles observes. “They’re the two artists – père et fils – who totally personify France. Many people forget that Renoir’s most celebrated paintings were bought by the Americans, not by the French.”

Indeed, the next chapter of the Renoir family saga began when Jean, who was fleeing the Nazis, arrived in the United States in 1940. He became an American citizen and lived there for the rest of his life.

“Jean’s son, Alain – the only child he had with Andrée, the heroine of my movie – arrived in California at the age of 20,” says Gilles. “At that point, Jean Renoir asked him to join the United States Marine Corps, telling him that he owed it to the country which had welcomed him. So Alain, who didn’t speak a word of English, went off to sea, although nothing obliged him to do so. Later in life, Alain Renoir became a professor of literature at Berkeley University, in 12th century literature – his children and grandchildren are American.”

Although Gilles says that he’s extremely pleased about the nomination of Renoir as France’s Best Foreign Film in the Academy Awards 2014, he’s less concerned about his chances of pocketing an Oscar in March.

“The Academy Awards are a kind of end-of-the-year ball for the cinema industry,” he says, with a grin. “It would be the occasion to buy a very beautiful dress for my wife and new shoes that would hurt my feet.

“I’ve also learned something from Pierre-Auguste Renoir, he believed that the only reward for work… is the work itself.”

La Domaine des Collettes, Cagnes-sur-mer

Hidden away in a century-old olive grove, the Musée Renoir at the Domaine des Collettes on the Côte d’Azur has reopened after a massive 18-month restoration. Among the works on display are 15 garden landscapes and bathing scenes painted by Auguste during his final years, plus over 50 sculptures and bronzes dating from 1913-1917, many of which were collaborations with Richard Guino and other artists. The highlights include a visit to Renoir’s atelier, and a stroll through the hilly terrain of orange groves and wild roses, with a sublime view of the sea.

Originally published in the February-March 2014 issue of France Today

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *