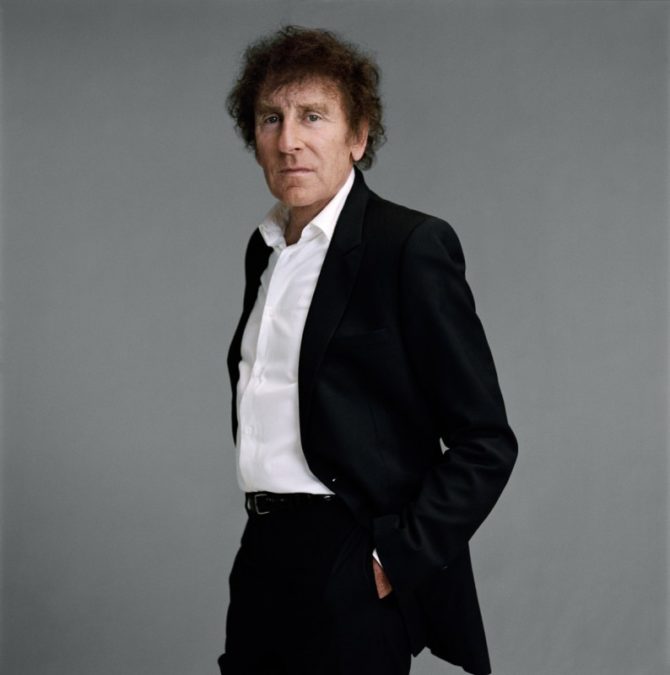

Alain Souchon

Perched on a stately Louis XV sofa in the lobby of a posh hotel off Place de la Concorde, Alain Souchon doesn’t seem quite at ease. Polite but distant, he looks like the little boy who was always the class loner, lost in his own world. Maybe that’s what first charmed French audiences more than 30 years ago and has kept them coming back ever since. Widely considered one of French pop music’s major artists, the singer famed for the antimaterialist anthem Foule Sentimentale proves in his latest album that he has lost none of his flair. The 12 songs in Ecoutez d’Où Ma Peine Vient, released in December, are pure Souchon: a tender, graceful blend of poetry and political conscience.

Born in 1944 in Casablanca, Morocco, Souchon grew up in Paris. A shy, introspective child, he withdrew deeper into hisshell as a teenager after his father died tragically in a car accident. His mother, seeing her son increasingly unable to deal with his classmates, sent him to London to attend a lycée français, but he preferred writing instead, both poetry and prose. To support himself, he took bartending jobs in seedy pubs where his duties included mopping up after patrons who’d had one too many. Even that didn’t bother him much, he says-all that mattered was his newfound passion for music.

“The Beatles had just taken off,” he recalls. “There were dozens of rock bands with young people my age making frenzied, pounding music-it was fascinating.” Deeply influenced by that British beat, he was among the first to spread the sound in France, one of a young generation of long-haired singers that included Michel Jonasz, Julien Clerc and Laurent Voulzy. In this formative period, the poetry of Bob Dylan and the sensibility of Jacques Brel also left their stamp on his work.

After years of playing small Left Bank cabarets, Souchon finally came to national attention in 1973 when one of his songs won the annual Rose d’Or competition in Antibes. Around the same time, he began working with Laurent Voulzy, a gifted composer who complemented his skills as a lyricist perfectly and would become his career-long collaborator. The duo’s little-noticed first album, J’ai Dix Ans, came out in 1974; a second followed two years later. The breakthrough came with their third effort, Jamais Content, in 1977. More than the title song, fans adored Souchon’s signature hit Allô Maman Bobo, in which he whimsically evokes his mal de vivre. With his curly hair and mohair sweater, he established the image of an eternal teenager, sensitive and vulnerable-an image that has endured throughout his career.

In tender but disillusioned ballads, the singer lays bare the precarious masculinity of men today, struggling with women and the hardships of love. “I’ve been very lucky: I met my wife early on and we’re still going strong,” he notes. “But I see people around me, my friends, my relatives, suffering over love. It’s not easy-there are no rules, there’s no right or wrong path…. But in the end, people go crazy over love because it’s the most important thing there is.”

Souchon made his film debut in the early 1980s, playing a fragile, melancholic character much like his public persona in Claude Berri’s Je Vous Aime (I Love You All). He won kudos for his performances in Jean-Paul Rappeneau’s Tout Feu Tout Flamme

(All Fired Up) and especially Jean Becker’s L’Eté Meurtrier (One Deadly Summer), starring Isabelle Adjani, with Souchon as the timid, lovestruck Pin-Pon. But his dalliance with cinema would remain a brief sidetrack: “I didn’t feel I was good at it,” he explains. “And honestly, I didn’t enjoy it all that much.”

Turning back to music, Souchon involved himself in a broader range of social issues. He was a founding member of Les Enfoirés, a loose-knit group of pop stars who performed for free to support Les Restos du Coeur, a charity dedicated to feeding the poor. His songs addressed topics like entrenched racism (Poulailler’s Song) and the tribulations of loneliness (Ultra Moderne Solitude). After a hiatus of a few years, Souchon resurfaced in 1993 with the critical and commercial hit album C’est Déjà Ça, including the song Foule Sentimentale, which would become the theme song for a whole generation of youth disenchanted by materialism. “People have always had hope that we’re making progress, that human society was headed for better things,” Souchon explains. “When I was a kid in the fifties, everyone thought the year 2000 would be terrific, we’d all be going around in little individual helicopters, it’d be so cool…. Now we’ve gone past that date and for the first time people are thinking that the planet’s a mess, with poisonous air and disastrous food. For the first time, the future looks really frightening.”

In Ecoutez d’Où Ma Peine Vient, Souchon continues in roughly the same vein. He recalls with nostalgia the train trips of his youth or the memory of a live concert in Algeria, but mostly he focuses on the disasters of modern capitalism. The album’s first song, Rêveur, deplores a generation’s failure to live up to the ideals of the Sixties: “Looking at the May ’68 movement, at the hippies, their impulse toward a kinder, gentler way of life, I really believed that once people Paul McCartney’s age came to power, the world would be a better place. As it turns out, it’s quite a bit worse,” he says with a wry laugh.

While he continues to sing and to denounce inhumanity in all its forms, Souchon has no illusions. “I don’t know if my songs can really change anything. Maybe they make people feel better. I’m singing about

sunsets, about the days when there were sleeping cars on trains, or shameful golden parachutes-it’s all totally commonplace, but it’s so commonplace that nobody dares to say it! So when you hear it in a song on the radio and think ‘Yeah, I feel that way too’, it’s a reaffirmation. Maybe my songs can cheer people up somehow.”

The new album, issued a month later than planned so he could include a last-minute song written with Voulzy, is clearly still a matter of anxiety for the singer. Despite his 35-year career, Souchon admits to a fear of failure. “It’s kind of pretentious, almost ridiculous, to write songs and then get up and sing them to people, kind of absurd,” hesays. “At least when people like them, you tend to forget about the absurdity. But what if they don’t?” It’s a fairly good bet that fear is unfounded.

Originally published in the January 2009 issue of France Today.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email