The Musical Angels of Nicolas Flamel

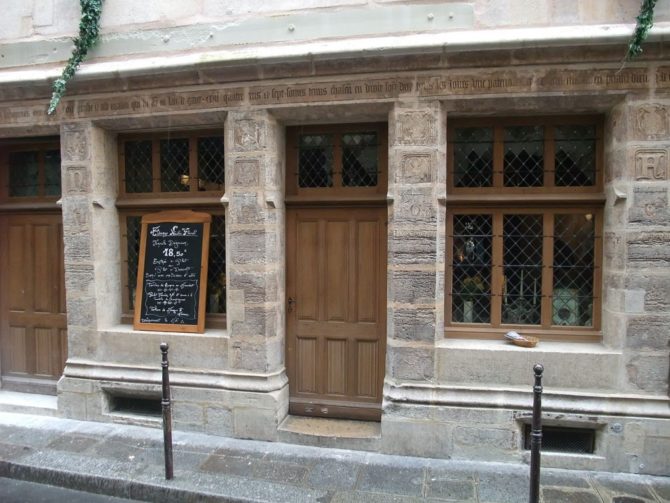

A lovely stone house on a long narrow street in the Marais served as refuge for poor itinerant laborers who came from the provinces to cultivate the nearby market gardens. In exchange for a meal and a beer at the ground-floor tavern, and a room on the upper floors, they had a simple obligation to fulfill, carved in stone in a long strip above the entrance: “We men and women laborers living at the porch of this house built in the year of grace 1407 are requested to say every day a Paternoster and an Ave Maria, praying God that His grace forgive poor and dead sinners.”

The house, at 51 rue de Montmorency, belonged to the prosperous and generous Nicolas Flamel, a sworn juror of the University of Paris, who made his fortune giving legal consultations and as a scrivener, copying and embellishing manuscripts—an important career in that era before the printing press. Flamel set up his shop across the river in the rue des Escrivains—Writers’ Street—where he taught his trade of copying prayer books, hymnals and texts. He married the wealthy widow, Dame Pernelle, like Flamel a devout Catholic; they lived simply and dedicated themselves to philanthropy. Together their fortunes grew thanks to astute real-estate speculation.

And perhaps, also, to their shared passion for alchemy: legend lends Flamel fabulous powers. With precious secrets from his library of ancient texts, and a battery of instruments, Flamel claimed in 1382 that he had transformed mercury into gold. (And it’s as an alchemist that he has been immortalized in fiction, from Victor Hugo’s Notre Dame de Paris to J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.)

But the real magic he worked was as a draftsman, a talent essential to his craft as copyist. It is believed that he designed his own tombstone, today part of the collection of the Musée de Cluny, the Musée National du Moyen Age, in Paris.

The marvelous quartet of angel musicians carved on stone panels flanking the doorway of 51 rue de Montmorency appear to be of the same hand—stylistic touches of curly hair and moon-shaped haloes are echoed in these illustrations. Despite the passage of centuries, the expression of an affectionate humanism endures in angels’ wide eyes, jaunty smiles and feathery arched wings.

During the Middle Ages, the representation of angel musicians evoked the divine harmony of the cosmos. Wind instruments, such as the angel’s Provençal pan flute—depicted here in exquisite authenticity, complete with shoulder strap—were believed to evoke divine power. Stringed instruments, such as the hand-held harp, psaltery and three-stringed mandolin of Flamel’s other three angels, suggested the manifestation of heavenly harmony. All four of these angels’ instruments are portable, as if chosen for ease of flight.

The psaltery, a stringed instrument of the harp or zither family, dates to ancient Greece. Its name derives from the Greek psallo, to touch sharply, or to pull, and indeed the angel plucks vigorously at the strings while tilting his head as if to verify the tuning.

The small harp, held by its graceful bowed pillar in the angel’s right hand while he plays with his left, was popular with medieval bards and troubadours. A cheery angel strums the lute, a teardrop-shaped, three-stringed instrument popularized first by the Moors of Spain before spreading throughout the Mediterranean region. The angel’s lute is typical of the medieval version, with its angled neck holding the low-tension strings firmly in place. Vestiges of its tuning pegs are still visible.

The Provençal fresteu, or pan flute, made of multiple reed or wood pipes, was known as the shepherds’ flute in France. It’s shown being played in the most eroded of the angel portraits, its construction, with a transversal bar, just barely discernable. Among the joys and charms of Gothic art is its determined veracity of detail. Flamel’s angels wear clerical robes with cowl collars, long full sleeves and narrow wrists, as if dressed for a church choir. They are set in frameworks of finely beveled columns in an impressive documentation of early 15th-century architecture.

That the house is still standing—and today open to the public as a restaurant—is something of a miracle. By the first decade of the 17th century, most medieval Parisian houses, constructed of wood, straw and clay with overhanging wooden gables so vulnerable to fires, had either burned to the ground, collapsed or been destroyed. What saved the sublimely decorated 51 rue de Montmorency was most likely its sturdy stone construction and its location on a narrow side street, out of the path of Haussmann’s demolition crews during the mid-19th-century renovation of Paris.

Nicolas Flamel lived to the prodigious age of 88. He bequeathed several hospitals and charitable foundations, as well as his many properties and their income, to the church of Saint Jacques la Boucherie for the distribution of alms to the poor. The nearby rue Nicolas Flamel intersects with the rue Pernelle, named for his wife.

Rosemary Flannery is an American living in Paris. Her book, Angels of Paris: An Architectural Tour Through the History of Paris, was published by The Little Bookroom in November 2012. 228 pages. $18.95.

Originally published in the December 2011 issue of France Today; updated in December 2012.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *