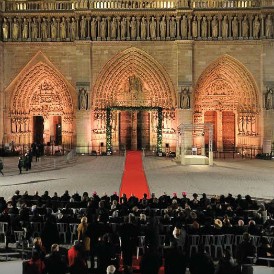

Notre Dame Celebrates a Birthday

Let’s clear matters up from the start: it is the 850th birthday of the founding of Notre Dame— the laying of the cornerstone in 1163—that is being celebrated this year, not the anniversary of the finished cathedral. It took roughly a century to build the basic edifice, and nearly another century until it was completed in 1351.

The new cathedral was meant to replace two Romanesque churches on the Ile de la Cité, Saint Etienne and an earlier Notre Dame. Saint Etienne stood roughly where the current cathedral does, and was beautifully decorated with mosaics probably recycled from an earlier Roman temple on the site, dedicated to Jupiter. Notre Dame was situated to the west.

Captured by Vikings in the 9th century, Saint Etienne was spared when a ransom was paid; Notre Dame was destroyed, and rebuilt soon after. Both churches were in sorry condition when Maurice de Sully became bishop of Paris in 1160, and they were also too small to accommodate the city’s speedily growing population— good enough reasons for replacing them with a more glorious edifice. But the building of Notre Dame was above all a political act, supported by the monarchy. Previously, Paris had been under the authority of the bishopric of Sens; the new cathedral symbolized the shift of spiritual authority to Paris, the king’s chosen capital.

Two years after construction began, on August 25, 1165, Maurice de Sully baptized Louis VII’s newborn son, the future king Philippe Auguste, sealing the alliance between church and state—a remarkable achievement for a man who was born to a peasant family in Sully-sur-Loire. Yet although that alliance held for generations, only two monarchs were ever crowned at Notre Dame: in 1431, Henry VI of England, who claimed the throne of France (and inspired Joan of Arc to aid the legitimate heir, Charles VII); and Napoleon, who crowned himself as emperor in 1804. On the other hand, royal funeral masses were often celebrated in Notre Dame, before burials at the basilica of Saint Denis, the traditional royal necropolis just north of Paris. More recently, funeral masses for the former French presidents de Gaulle and Mitterrand were celebrated in 1970 and 1996.

The envy of all

The laying of the cornerstone, in spring 1163, was attended by Louis VII and presided over by the exiled Pope Alexander III. The pope’s presence enhanced the political momentum, and helped soften the humiliation inflicted on Maurice de Sully a few weeks earlier at the abbey of Saint Germain, when he turned up uninvited at the consecration of the abbey church—now Saint Germain des Prés—and was duly turned away. Nothing personal, just a demonstration of the abbey’s independence. The radical reconstruction of the church of Saint Denis, completed just two decades earlier, had offered the world the first grand example of Gothic architecture, to the immense envy of prelates elsewhere in the kingdom. In no time the Gothic cathedrals of Sens, Noyon and Senlis were underway, prompting Paris to follow suit.

The ribbed vaulting, the pointed arches, the flying buttresses were the expression of spectacular architectural innovation, but also of new aesthetic principles. They created an energy that elevated the soul towards the heavens, and at the same time provided a shelter of harmony, peace and comfort. But what was then known as the new “French style” of architecture also served the political purpose of placing Paris at the center of Christianity—hence the creation of an ambulatory around the nave of Notre Dame, vast enough to accommodate processions of thousands of pilgrims.

Outside, the cathedral’s twin towers, 226 feet tall, enhanced the symbolism as they soared above the skyline. At first the cathedral square—le parvis (from paradisus, paradise)—was only one-sixth its present size, which made the towers seem even taller, bestowing on the beholder a feeling of awe, especially since visitors approached it through the densely built-up quarter around rue Neuve Notre Dame, which lay in the axis of the central portal.

Miracles and mistakes

The basic structure of the original cathedral has survived—the walls, vaulting, arches, pillars and the flying buttresses that hold it all together. But much has disappeared, and revolutions and insurrections don’t bear all the blame. Many elements were eroded by time, notably the polychrome sculptures. Others fell prey to changing tastes, especially after the turn of the 18th century when the “barbaric” Gothic style went out of favor. It’s hard to believe that Jules Hardouin-Mansart—the great architect of the Invalides church, the Place Vendôme and the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles—was responsible for the destruction of Notre Dame’s gorgeous rood screen. Jacques Germain Soufflot, the architect of the Panthéon, did away with the initial central portal to make room for a larger dais.

The original stained glass was replaced by plain panes to bring in more light. It’s a miracle that the north rose window has survived almost intact. By the end of the Revolution, after first becoming the “Temple of Reason”, the cathedral was used for storage. By then it was a shabby sight, earmarked for demolition and put up for sale. It is another miracle that the transaction fell through. The potential buyer, Claude-Henri de Rouvroy de Saint-Simon—was a philosopher and social theorist from the same aristocratic family as the illustrious Duke of Saint Simon, author of the famous Memoirs. Thanks are due to Victor Hugo for raising the alarm. The Hunchback of Notre Dame, written in 1831 for the purpose of alerting public opinion, led to the rescue of the cathedral and its restoration by the architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, a colossal undertaking that lasted from 1844 to 1864.

Barely seven years later, in May 1871, Notre Dame narrowly escaped destruction again during the uprising of the Commune, when the Communards piled up the pews in the center of the nave and set them on fire. This time salvation came from the doctors of the nearby Hôtel Dieu hospital, who put out the fire before it spread. Adolph Hitler too seems to have been set on the destruction of Notre Dame as Nazi troops were forced out of Paris in 1944, but to no avail. For the most part it is Viollet-le-Duc’s legacy that present generations contemplate, “an edifice reestablished in a complete state that could have never existed before”, as he described it—in other words, a reinterpretation of a medieval church, not a replica.

On the main facade for example, only Saint Anne’s portal, to the right of the center door, dates from the origin of the cathedral. The 28 kings of Judah lined up in the facade’s gallery are all 19th century statues; the originals, mistakenly thought to represent the kings of France, had their heads chopped off during the Revolution. Twelve of the severed heads were later rediscovered and are now on display at the Musée de Cluny. The gargoyles, the chimeras, the graceful spire and most of the other current decorations were made by Viollet-le-Duc.

Brand new bells

Oddly enough, it’s the facade ignored by most visitors, on the north side along the rue du Cloître Notre Dame, that still offers a cluster of original features. Most notable is the Cloister Portal by sculptor Jean de Chelles with its carvings of the life of the Virgin Mary and the legend of Theophilus, who sold his soul to the devil. In the trumeau, or central pillar, stands the original statue of Notre Dame, dating to 1260. Beyond it, Pierre de Montreuil’s Porte Rouge originally led directly to the cloister; in its tympanum statues of King Louis IX—Saint Louis—and his queen Marguerite de Provence kneel before the Virgin.

Victor Hugo had a special fondness for the bells of Notre Dame—witness his creation of the bell-ringer Quasimodo. There were eight bells in the north tower, gone with the Revolution, and two colossal bells in the south tower—one named Marie (also gone), and the other Emmanuel. Emmanuel was initially named Jacqueline, after the wife of Jean de Montaigu, who offered the bell in 1400 in thanks for the birth of his daughter. In 1681 Louis XIV had the bell brought down to be alloyed with bronze and renamed it Emmanuel-Louise-Thérèse. It’s said that the women of Paris brought their silver and gold jewelry to be melted down into the bell as well, which accounts for Emmanuel’s perfect F-sharp pitch, one of Europe’s purest peals. The four bells installed in 1856, during Viollet-le-Duc’s restoration, never had a satisfactory sound. To mark this 850th birthday, they are being replaced by eight new bells, cast at the Cornille-Havard foundry in Villedieules- Poêles in Normandy. They are named: Gabriel for the archangel, Anne-Geneviève for the mother of Mary and the patron saint of Paris; Denis and Marcel for the city’s first and ninth bishops; Etienne for the earlier church on the site and for Christianity’s first martyr; Benoît-Joseph for the recently resigned Pope Benedict (Benoît) XVI, Joseph Ratzinger; Maurice for Maurice de Sully and Jean-Marie for the late Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, the 139th archbishop of Paris.

In the south tower, Emmanuel will now enjoy the company of a new Great Bell, another Marie, cast by the Dutch Royal Eijsbouts foundry. Altogether, the new bells amount to a €2 million project, with the funds raised by private donors. The new bells arrived in Paris on January 31, and—with big Marie in the lead and crowds all the way— were paraded down the Champs Elysées to the cathedral, where they were displayed through February 25. Their chimes will be heard for the first time on March 23, the eve of Palm Sunday. Once more the sound of Notre Dame’s bells, cherished by Victor Hugo and lost with the Revolution, will ring in celebration of the birthday this year and, it may be hoped, continue to ring out for centuries to come.

Thirza Vallois is the author of several books on Paris and France www.thirzavallois.com

Originally published in the March 2013 issue of France Today

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *