Lyon’s Traboules

Saturday afternoon, and the streets of Vieux Lyon, the city’s old town center, are packed with shoppers and tourists. My guide and I stop by a heavy wooden door, right next to a convenience store. She taps the code into the keypad, the door swings open and we step from the busy street into a dark passage, barely three feet wide. As the light comes on, I see that the narrow alley opens onto an interior courtyard in a 15th-century house. We have suddenly ducked into a different world. A world of mullioned windows, Gothic galleries, ancient wells, fountains and a spiral staircase carved out of stone—a miracle of medieval engineering.

Lyon has several of these secret courtyards, stark contrasts between past and present, many of which can only be reached by one of the city’s distinctive traboules—passageways that cut through a house or, in the case of the longer traboules, a whole city block, linking one street with another. If you know where to go, it is possible to walk around the Vieux Lyon and the Croix-Rousse districts via the traboules, avoiding the crowds—and sheltered from the rain.

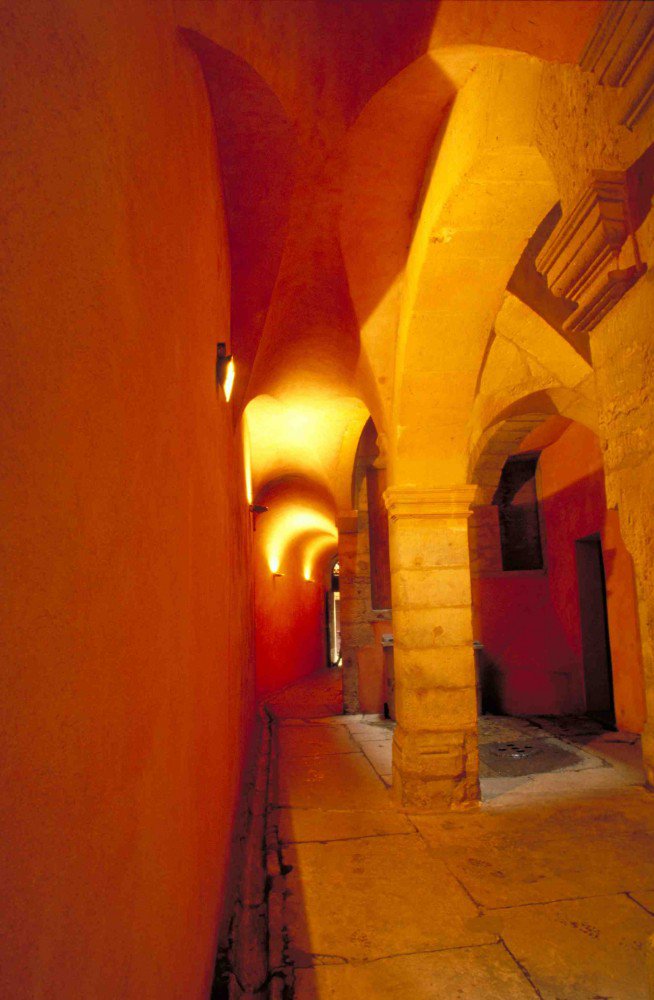

Credit: © RA Tourisme / M. Kirchgessner

La Tour Rose

Traboules are found in other French cities, but in most cases, unless you happen to live in a house that has one, you won’t know they are there. Lyon is different. Dozens of its 300 or so traboules are open to the public, thanks to an innovative agreement between the city council and the inhabitants of the pertinent buildings. The city bought up many of the properties surrounding the traboules and made them available as low-cost housing, but with strings attached. Residents around a traboule must agree to keep it open to the public between 8 am and 7 pm. But like the traboules themselves, the agreement is a two-way street.Visitors are expected to be quiet, and respect the fact that the apartments surrounding the fascinating old passages are private homes. Unfortunately, in some cases the bargain has not been kept—on one side or the other—and now some of traboules that should be open to the public are accessible only to residents.

Credit: © M. Perrin / OT Lyon

The Cour des Voraces in Croix-Rousse during Lyon’s Fête des Lumières

Romans to riches

The word traboule comes from the Latin trans ambulare, meaning “to cross”, and the first of them may have been built as early as the 4th century. As the Roman Empire disintegrated, the residents of early Lyon—Lugdunum, the capital of Roman Gaul—were forced to move from the Fourvière hill to the banks of the river Saône when their aqueducts began to fail. The traboules grew up alongside their new homes, linking the streets that run parallel to the river Saône and going down to the river itself.

For centuries they were used by people to fetch water from the river and then by craftsmen and traders to transport their goods. By the 18th century they were invaluable to what had become the city’s defining industry: textiles, especially silk.

Credit: © RA Tourisme / A Perrier

A traboule near the rue du Boeuf in Vieux Lyon

The silk weavers were known as canuts, and their trade changed the face of Lyon forever. (Canut may derive from canette, a spool for thread.) High-ceilinged houses were built to accommodate the enormous Jacquard looms, which were some 13 feet tall. On the outskirts of town, Croix-Rousse—now Lyon’s chic bobo (bourgeois-bohème) district—was originally a working-class area, home to the majority of the city’s 90,000 silk weavers. They used the traboules to carry their bolts of silk down to the markets in the new city center on the Presqu’île, the narrow peninsula between the Rhône and Saône rivers. The covered traboules were the quick way, and had the advantage of protecting their precious goods from the elements.

Weavers’ revolt

The traboules played a part in the important canut revolts, the first of which erupted in November 1831. These riots by Lyon’s exploited silkworkers were probably the first documented uprisings of Europe’s Industrial Revolution.

Economic times were hard, the demand for luxury goods like silk had been drastically reduced, and at the time the price of silk varied from merchant to merchant. To provide a bit of security, the workers wanted to obtain a fixed tariff for the piecework they produced. The canuts asked the prefect of the region to help with negotiations, but his intervention was largely unsuccessful and dozens of the big manufacturers refused to apply the fixed rate, claiming it was against the principles of the French Revolution.

The enraged workers gathered in the traboules and marched through them to the center. After a bloody battle, the rioters took control of the town, helped enormously when the national guard changed sides. Victory, however, was short-lived. A few days later, King Louis-Philippe—who had just acceded to the throne after the July Revolution—sent a 20,000-man army from Paris to retake the city. Order was swiftly restored, the fixed rate abolished, the prefect dismissed, the national guard disbanded and a large garrison stationed in the city center.

The revolt may have failed, but it set the stage for a century of worker revolutions. Tourists from Russia and Eastern European are all quite familiar with the tale of the canut revolts, says Lyon city guide Françoise von Scheidt, since they were historically important for their countries, too. The second uprising in 1834—this time over salary cuts—was again put down. In 1848, shocking working conditions brought the canuts into the streets once more, again to no immediate gains.

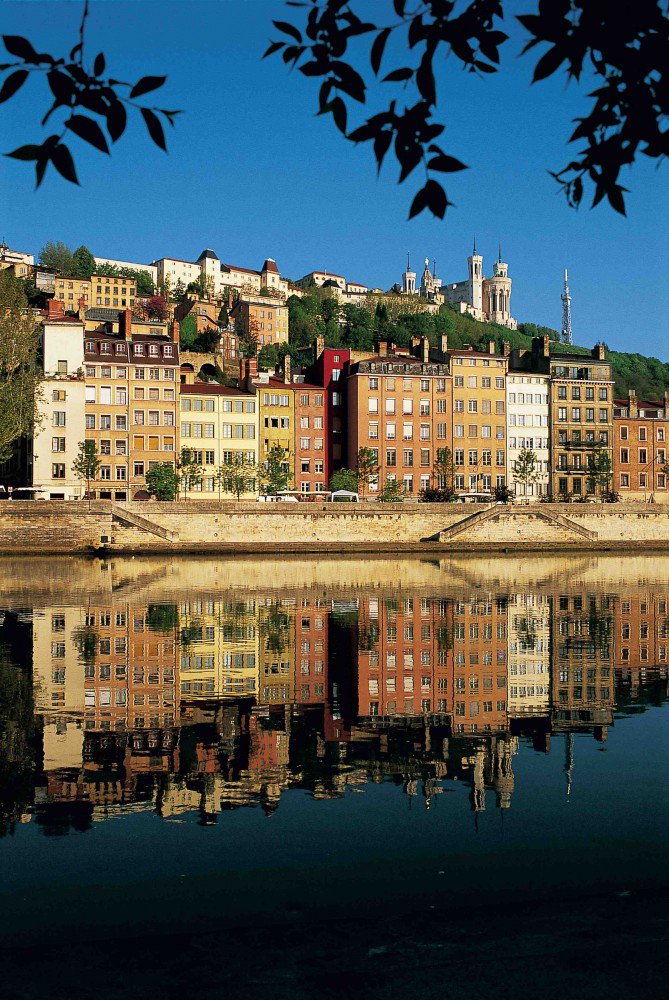

Credit: © Tristan Deschamps

Vieux Lyon on the Saône River

Wine and war

The authorities were also determined to cut the rate of alcoholism among the workers, and decided that a carafe of wine would, from then on, contain less wine—although it would remain the same price.Unsurprisingly, the workers were outraged and apparently gathered one night in a large traboule courtyard in Croix-Rousse called the Cour des Voraces to claim their rightful, full-size carafes of Beaujolais. Today the Cour des Voraces is a symbol of Lyon as well as probably its most spectacular traboule, with three different entrances: the Place Colbert, the Montée Saint Sébastien and the rue Imbert Colomès. Inside, a plaque reads: “In the Cour des Voraces, hive of silkwork, canuts struggled for their lives and their dignity.” Like many of the traboules and interior courtyards in Lyon, it is also a showcase for an impressively complicated stairwell, in this case an immense six-story set of slanting stairs built of stone from the nearby Mont d’Or hills.

Traboules also played a part in World War II, when Lyon was both a central command point for the occupying German forces and a stronghold of the Resistance. The dark, shadowy traboules were perfect boltholes for escaping and hiding from the Gestapo, especially in the early days of the occupation, when only the Lyonnais knew of their existence. People fleeing from German raids were able to use them as shortcuts or ways to give their pursuers the slip. In fact the office (more accurately, one of the offices) of renowned Resistance leader Jean Moulin is just a few steps away from the exit of a Croix-Rousse traboule, at the Place des Capucins, next to what is now the Church of Scientology.

La Tour Rose

It’s in Vieux Lyon that you can see the majority of the beautiful interior courtyards that are tucked away from view. In the 14th and 15th centuries several Lyonnais families made fortunes in the city’s famous trade fairs. One such family was the Thomassins, who built a splendid hôtel particulier on the Place du Change in the old town. With its delicate arches and Gothic facade, it is well worth a visit. But don’t stop there. Squeezed between the mansion and a pharmacy is a hefty, metal-studded wooden door with a grill at the top. Beyond it lies an interior courtyard once in a state of complete disrepair but restored over recent years and now complete with mullioned windows, neo-Gothic crosses and other fancies, galleries and a low, vaulted écurie, a former stable block.

Credit: © Marie Perrin / OT Lyon

The carved stone circular staircase at La Tour Rose

Among the most famous of Lyon’s not-so-secret passageways is the Traboule de la Tour Rose. The entire courtyard is painted in pleasing pastel and ochre tones, dominated by an elegant pink Renaissance watchtower housing a giant spiral staircase with arched windows all the way up. (The stairs are now off limits to the public.) At the back of the courtyard is the photo gallery and shop of Frédéric Jean, and it is only thanks to his presence that this traboule remains open, since the surrounding apartments are not social housing.

La Longue Traboule is, as its name implies, the longest traboule in town. It runs through four houses in the old town and links the rue du Boeuf with rue Saint Jean, with three separate courtyards. It is said that, to be a true Lyonnais, you need a working knowledge of the traboules. There are guided tours, of course, but with a little detective work visitors can find them on their own. In the Old Town, the most impressive of them are marked with shield-shaped bronze plaques, while in the Croix-Rousse a lion’s head on a blue background points the way.

Originally published in the February 2012 issue of France Today

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY