Glove Love: A History of Glove Making in France

As is sometimes the case in France, this story begins with a cheese – the noble Roquefort, born of the rocky and arid scrubland of limestone plateaus and deeply etched valleys of the Southern Massif Central, where the landscape, unfit for farming, is ideal for raising sheep. Although impossible to say when the creamy blue-veined cheese first made its appearance deep in the caves of the Aveyron, its first recorded mention is in 1070 and other evidence places it back perhaps 1,000 years earlier. Certainly one of the oldest cheeses in France, it’s mass production led to the birth of another esteemed French industry – glove making.

To keep the ewe’s milk for this most popular of cheeses flowing, lambs were slaughtered shortly after birth, when their skins were too small and delicate for making much of anything, yet perfect for a pair of gloves. Situated on the river Tarn, and therefore convenient for tanners, nearby Millau, a town that dates back well before Roman times, became the glove making centre of France.

Now most famous for the soaring Viaduc de Millau, glove making in Millau dates at least back to the Middle Ages and reached its apex in the mid-20th Century, when the city produced nearly five million pairs of gloves a year and exported them worldwide.

Although gloves in some form have been worn since there have been hands to put into them – and have made their appearance on notable Frenchmen in the form of gauntlets for knights, ceremonial gloves for church officials and elaborate models for sovereigns – their rise as a feminine fashion accessory didn’t occur until the early 16th Century and is indisputably the work of Catherine de’ Medici.

When Catherine came to France from her native Italy in 1533 as the new wife of Henry II, noble-women’s fashions, though expensive and luxurious, were expected to show a modest restraint. It was the men who flaunted the frills and fripperies, jewels and laces. This custom confounded and infuriated the proud queen, who set out to change all that, and much more besides. Catherine was vain about her hands and she found that gloves not only guarded her most prized feature but also enhanced their beauty and drew attention to their gracefulness. Catherine championed the wearing of gloves for day or night and delighted in commissioning the most elaborate designs, which she often bestowed as a sign of her high esteem. The silk or leather gloves she dispensed among her favourites were so fine they could be rolled up and presented in a walnut shell polished to a brilliant sheen. Women of the court took to wearing the shells on chains to proclaim their status with the queen.

A Glove Renaissance

But a gift of gloves from Catherine was not always a welcome one. Her rival, the Protestant Jeanne de Navarre, is said to have met her end via a pair of poisoned gloves, a gift from Catherine. Though almost certainly untrue, the story lingers in history, overshadowing another innovation attributable to Catherine – the perfumed glove. This evocative item was sometimes so fragrant that it was hard to tell if a suitor swooned from sheer desire or from the overwhelming effect of a perfume-drenched glove.

Over the following centuries, as gloves became a wardrobe staple among fashionable French women of all social classes, materials for glove making proliferated, with kid – the skin of milk-fed baby goats, unequalled for its pliancy and resiliency – replacing lambskin as the dominant material for finer gloves, and materials like doeskin, peccary (from the wild Mexican boar), reindeer, calf, suede, chamois, sheep and snakeskin made an appearance.

In the 1960s, when fashion shed its gloves and much else besides, the industry plummeted, and by the 1980s, Millau had lost all but a handful of its eminent glove makers.

Since then, gloves have never quite recovered their status as the wardrobe staple they were when our mothers and grandmothers were matching them with shoes, hats and handbags, but in the last 10 years fashion gloves have been making a steady comeback in Paris, and the fashion world has taken note.

Led by three Millau-based glove makers, each employing an expertise cultivated over generations, gloves are enjoying a new and exciting renaissance in fashion. For the Maisons Causse, Fabre and Lavabre Cadet, perfecting the ancestral methods of one of France’s distinguished traditions and an important part of its luxury heritage, is only one aspect of their ancient trade. Bringing the glove resoundingly into the 21st Century is the other – and it is a challenge they have fully embraced.

Of the three houses, Causse is the oldest, founded in 1892 when brothers, Jules, Henri and Jean, all working as cutters at a glove making factory in Millau, decided to strike out on their own. Five years later, the brothers split off, Jules and Henri taking their expertise across the Atlantic to Gloversville, NY, the centre for glove making in the United States, leaving Jean to man the Millau business on his own. Undaunted, the enterprising Jean grew the business from a small cottage industry to a large factory employing dozens of people, building Causse’s reputation for craftsmanship. His son Jean took the family business into its glory years, when the name Causse could be found in finer department stores worldwide.

Jean’s two sons joined in the mid-50s and worked enthusiastically to modernise the facilities and encourage new designs to keep up with fashion trends, especially the newly emerging sportswear styles.

Combining technical innovation with fashion was the key to Causse’s success when the glove business entered the crisis years from the 1970s to the 1990s. Instead of folding, as scores of Millau glove makers did, Causse bought up two key competitors, one of whom had furnished gloves to the top Paris fashion houses, and in 1999 hired two highly respected Paris-based designers who’d worked with some of the top Paris fashion houses.

Riding the wave of a renewed interest in the historical French luxury brands, Causse opened a state-of-the-art factory and museum in 2005 and two years later a boutique on rue Castiglione, a stone’s throw from Place Vendôme, Paris’s epicentre for French luxury brands. Causse’s first dedicated boutique in the world, the sleek wood-panelled showroom features gorgeous styles in exotic skins such as crocodile, as well as metallics, fur and even feathers, signalling the company’s return to haute couture glory.

Impeccable Craftsmanship

Sharing the rarified atmosphere at the top, Maison Fabre is also a fourth generation glove maker based in Millau. Fabre’s Paris boutiques include their flagship store at the Palais-Royal and a stylish branch in Saint-Germain-des- Prés. In April, Fabre opened a luminous new space in the new Cour des Senteurs in Versailles, dedicated to reviving the perfumed gloves once loved by Catherine de’ Medici.

Like Causse, Maison Fabre’s history is one of expertise, entrepreneurship and vision. Founded in Millau in 1924 and making mostly standard-issue white kid gloves, the house quickly succumbed to the vision of Rose Fabre, whose imagination took the company to new heights, employing 300 people for their haute couture creations.

Fabre weathered the lean years by supplementing their output with small leather goods (which have just been revived in a superb new edition as of autumn 2013), only to make a comeback in the early 2000s, opening their beautiful flagship store at the Palais-Royal in 2008.

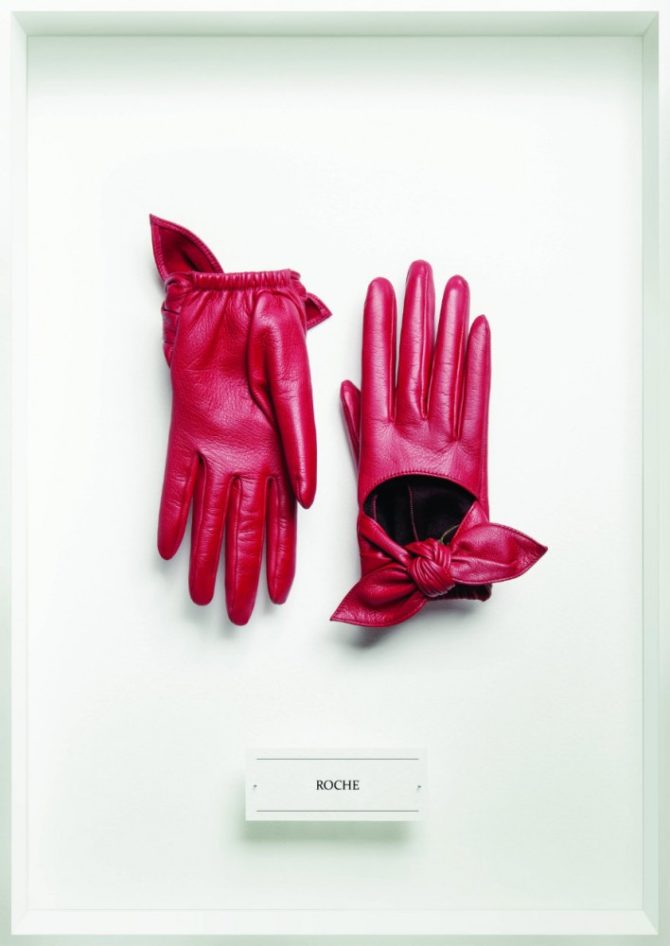

Combining impeccable craftsmanship and fit with unerring style, Maison Fabre offers classic styles that will last year after year, along with more playful designs, with the inner fingers in primary colours, and models meant to make a statement, like the Classique in a panther print or the Flanelle in lambskin with a deep rabbit fur cuff. Prices range from €85 to €130 for a classic model and up to €285 for a “mode” style. A model in a luxury skin, like crocodile, or a made-to-measure model can run from €900 to €2,000 a pair and for python between €180 and €560. This may seem high, but keeping in mind what goes into making a single pair of gloves, and the fact that cared for properly they’ll last a lifetime, it can be seen as a smart investment.

Artisan Expertise

All of the work in these gloves is done by hand or hand- driven machine and each pair takes a minimum of two hours, and an average of eight hours, to make. A special order couture glove can take days. Tanning and dying the pelts is just the beginning. From there, it’s a process of meticulous and painstaking work, requiring a masterful feel for the leather that begins with the table cutters – the aristocrats of glove making – who stretch the pelt crosswise and lengthwise to retain the correct amount of give. Like each animal, each pelt is slightly different and it takes years to develop a feel for how the leather should be treated.

Next is stitching. There are six different stitching styles to choose from for the thumb alone and 11 more for the rest of the glove. The piqué style, where one edge is lapped over the other and stitched on the very edge so the seam is flat, elastic and smooth, is mostly used for fine gloves.

The final step is the laying off, where the still shapeless gloves are slipped onto metal hands the exact size and shape of the glove, and steam heated to shape the glove to perfection. From the raw state to the finished product there are no less than 90 inspections to ensure perfection.

For Lavabre Cadet, founded in 1946, sur mesure is the order of the day. Having earned the title, Enterprise du Patrimoine Vivant, along with several other important prizes, Lavabre Cadet is the only artisan glove maker left in Millau that measures in quarter sizes, and therefore can most sincerely use the phrase, “fits like a glove”.

Lavabre’s Palais-Royal boutique can set you up with a pair of personalised gloves in three to five weeks, in the style, skin and colour of your choice. Once the prerogative of aristocrats, Lavabre Cadet now caters to the likes of Catherine Deneuve, Salma Hayek and designers Rick Owens, Balenciaga and Vera Wang. Guaranteed for life, the gloves can be sent to the boutique for cleaning.

Maison Causse, 12 rue de Castiglione (1st) +33 1 49 26 91 43

Maison Fabre, 128-129 Galerie de Valois, Jardins du palais-royal (1st) +33 1 42 60 75 88; 60 rue des saints pères (7th) +33 1 42 22 44 86 Lavabre Cadet, 32-33 Galerie Montpensier, Jardins du palais royal (1st) +33 9 81 68 47 68

Originally published in the October-November 2013 issue of France Today

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *