A Gift for the Ages: The Statue of Liberty

It is hard to describe the feeling of awe mixed with patriotic uplift that one gets when approaching the Statue of Liberty by boat. The approach by ferry from Battery Park to the Statue is thrilling. I visited the Statue of Liberty as a child in the early 1950s and the 65 intervening years have neither dimmed that experience nor diminished any of my subsequent ones. It is grand in every sense.

Perhaps the best-known piece of sculpture in America, the huge female figure of liberty enlightening the world commands New York Harbor. Standing 151 feet tall, atop a 142-ft granite pedestal, the statue portrays Liberty stepping from broken shackles. Her uplifted right hand holds a burning torch, while her left hand grasps the Declaration of Independence, inscribed “July 4, 1776.” A circular interior stairway leads from the top of the pedestal to Liberty’s spiked crown. From sunset to sunrise, 92 1000-watt bulbs floodlight the structure and 15 more illuminate the torch.

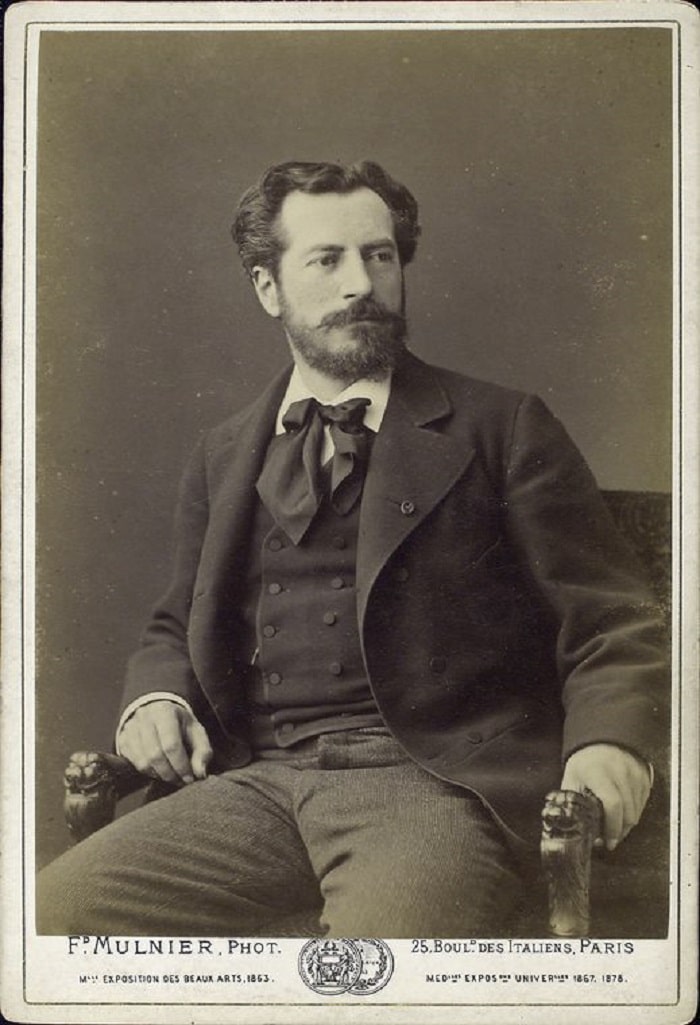

The statue was designed by noted French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. Its hand-hammered copper plates are supported by an inner iron framework crafted by Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, the French engineer. Bartholdi designed the statue at the conclusion of the American Civil War and proposed to offer it as a gift of the French people to commemorate “the alliance of the two nations in achieving the independence of the United States of America, and attest to their abiding friendship.”

Frederic Auguste Bartholdi. © New York Public Library Archives, Wikipedia Commons

Bartholdi chose to represent Liberty dressed as the Roman goddess, Libertas. Her seven-spiked crown was meant to evoke the sun, the seven seas, and the seven continents. Her torch was to represent liberty enlightening the world; the broken chain to refer to the abolition of slavery.

Libertas was a carefully considered choice. The Roman goddess was well-known to Americans — a popular symbol who appeared on most American coins of the time period and also atop the dome of the U.S. Capitol. She was also widely admired by emancipated slaves.

With his design in mind, Bartholdi then sailed to New York to look for a site. He chose Bedloe’s Island (now renamed Liberty Island) at the mouth of New York Harbor because all vessels arriving in New York had to sail past it. Bartholdi then met with President Grant who agreed to let him install the statue on Bedloe’s since the government no longer needed it for military defense.

Funding for the statue was a joint French-American project. The French paid for the statue and its transportation, the Americans for the pedestal and installation. In 1875, Bartholdi completed the torch-bearing arm first and exhibited it at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. He exhibited the head at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1878. By 1880, the French had raised $250,000, enough to pay for the casting of the statue. It remained for the Americans to raise money for the pedestal but times were hard and fundraising was slow.

Engraving of Emma Lazarus. © T. Johnson and W. Kurtz, Wikipedia Commons

The effort got a boost in 1883 when poet Emma Lazarus composed “The New Colossus,” a poem that inspired contributions. “The New Colossus” is now inscribed on a plaque on the front of the pedestal and it has become almost as famous as the statue itself:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

— “The New Colossus” (1883)

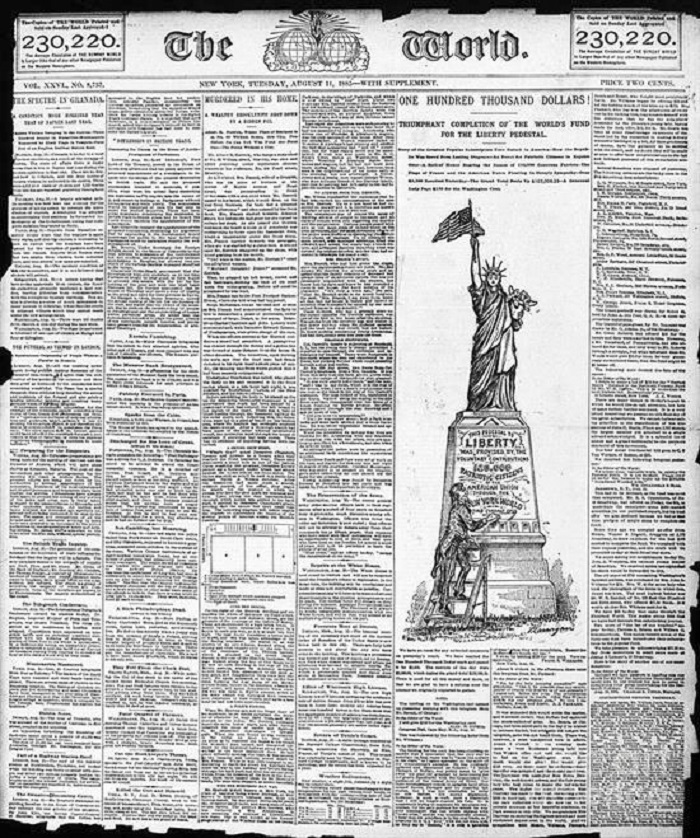

Statue of Liberty News. © Wikimedia Commons

The final push for the remaining $100,000 came from Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World, who pledged to print the name of every contributor in his newspaper. New Yorkers contributed by the thousands in amounts ranging from five cents to many thousands of dollars. All had their names published and some had their letters published as well. In all, Americans raised $300,000 — enough to pay for the pedestal and installation.

The statue was made and displayed in France, then disassembled and shipped to New York in 214 separate cases. It arrived in New York on June 17, 1885. Over 200,000 people lined the docks and hundreds of boats crowded the harbour to welcome the ship.

Immigrants approaching the Statue of Liberty. © Archive Holdings Inc./Getty Images

Reassembly took over a year. A power plant was constructed on the island to supply light for the statue, the pedestal was built and Frederick Law Olmstead, designer of Central Park, created the landscaping.

On October 28, 1886, the statue was dedicated. A parade led by President Cleveland began at Madison Square Park and proceeded south to the Battery. It is estimated that a million spectators lined the route. When it reached Wall Street, traders unfurled ticker tape from the windows of the New York Stock Exchange, raining it down upon the parade. This was the first ticker tape parade, kicking off a long tradition in New York City.

At the Battery, the parade took to the water, with President Cleveland leading the way on the Presidential yacht. On the island, Bartholdi waited with the statue draped under a huge French flag. Ferdinand de Lesseps, designer of the Suez Canal and head of the French fundraising committee, gave the first speech. The head of the New York Committee and President Cleveland were to speak next but, at that point, Bartholdi removed the French flag. The crowd erupted in cheers and drowned out most of what they had to say. From his notes, we do know what Cleveland intended to say: “The statue’s stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man’s oppression until Liberty enlightens the world.”

Immigrants coming into America. © Archive Holdings Inc./Getty Images

The Statue of Liberty holds a unique place in American hearts. It is visited by over 4 million people each year. Arguably the most recognisable and meaningful symbol of our country’s ideals, President Coolidge declared it a national monument in 1924 and the National Park Service has carefully tended it ever since.

The only way to visit the statue is to take a ferry. And that is the perfect way to experience it. Approaching on a boat with Manhattan laid out and gleaming behind it, it is easy to imagine the powerful emotional reactions of the millions of immigrants who first glimpsed it as they sailed into New York Harbor. Truly, the French gave us a gift for the ages.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in America, French history, history, statue of liberty

By Fern Nesson

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *