Eiffel and the Fair

On June 12, 1886, Gustave Eiffel was delighted to learn that he’d won the competition to build the centerpiece of the 1889 Exposition Universelle, the gigantic World’s Fair to be held in Paris. His project-which had bested such competitors as a gigantic replica of a guillotine-was for nothing less than the world’s tallest man-made structure. Its official name was the Tour en Fer de Trois Cent Mètres, but all the world would come to know the graceful 984-foot landmark as the Eiffel Tower.

Now, in honor of the tower’s 120th anniversary, Jill Jonnes has made Eiffel’s Tower the star of a compulsively readable popular history that not only recounts the challenges and triumphs involved in its construction, but also sets it memorably in the context of Belle Epoque Paris and the lively Franco-American rivalry that permeated the fair.

Winning the competition was just the first of the hurdles Eiffel had to clear. Many prominent Parisians objected to the design, including writer Guy de Maupassant, composer Charles Gounod and architect Charles Garnier, who claimed in an official petition that “the Eiffel Tower, which even commercial America would not have, is without a doubt the dishonor of Paris.”

Other problems included so much official foot-dragging over the initial contract that Eiffel doubted he’d be able to finish on time; a punishing schedule for his 200-plus workers to assemble 18,038 pieces of iron with 2.5 million rivets; the difficulty of ensuring the safety of blacksmiths and welders who worked, sometimes in freezing weather, on platforms hundreds of feet above the ground; and trouble installing elevators that rose at an angle, resulting in stairs-only access for the public for a short while.

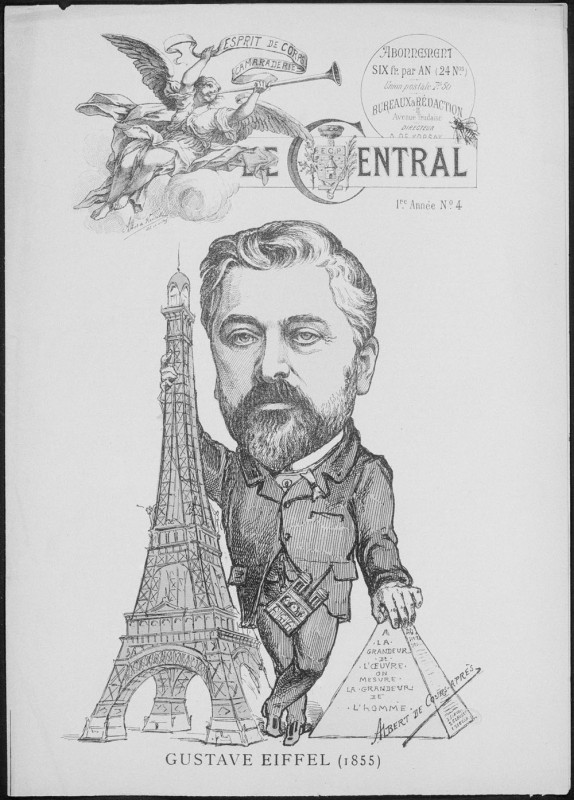

But Eiffel, a brilliant engineer and a self-made millionaire famous for constructing soaring railroad bridges all over Europe, met every challenge, starting with a design that had to be accurate to within a tenth of a millimeter. He financed the construction himself, settled strikes by disgruntled workers, and ended lawsuits, brought by local residents who feared the tower would topple over or attract lightning, by pledging to cover any damages from his personal fortune.

Jonnes, whose previous books include Conquering Gotham and Empires of Light: the Race to Electrify the World, is adept at making technical issues not only understandable but fascinating, and the race to meet the deadline makes compelling reading. When the tower opened-on time, on May 15, 1889-it was nearly twice the height of the previous holder of the tallest-structure title, the 555-foot Washington Monument, completed in 1884, and it would retain its title for 40 years, until New York City’s Chrysler Building, at 1,046 feet, topped it in 1929, followed by the 1,250-foot Empire State Building two years later.

The Universal Exposition, like the tower, was a huge success. Timed for the centennial of the fall of the Bastille-and therefore boycotted by Europe’s royals-it demonstrated France’s recovery after the disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, the bloody uprising of the Commune, and the political and economic turmoil that followed. It also celebrated the triumph of modernity on the verge of the 20th century, and some 30 million visitors marveled at technical innovations displayed by over 60,000 exhibitors.

Thomas Edison’s phonograph was one of the fair’s triumphs-when the inventor himself arrived in Paris he was fêted everywhere he went. Buffalo Bill arrived at Le Havre on the steamship Persian Monarch with a colorful crew of cowboys and Sioux Indians, 200 horses and 20 buffalo, and then continued by special train to Paris and set up camp in Neuilly, where his sold-out Wild West Show was a sensation. The petite Annie Oakley astonished crowds with her sharpshooting, and behind the scenes, artist Rosa Bonheur, a tiny silver-haired figure wearing men’s trousers, often set up her easel among the teepees and corrals, happily sketching and painting.

Other artists vied to be accepted in their respective nations’ arts pavilions-Gaugin, incensed at being excluded, hung his paintings in one of the fair’s cafés (they didn’t sell) and tried to convince Van Gogh to do the same (he wouldn’t). James McNeill Whistler, living in London at the time, quarreled with the organizer of the American painting show and exhibited with the British instead.

James Gordon Bennett, who’d launched a European edition of his New York Herald in 1887, gambled that the fledgling newspaper would succeed once Americans arrived for the fair. He won-it would survive as the International Herald Tribune.

Skillfully weaving mini-biographies of these and other characters throughout her briskly-paced narrative, Jonnes brings the World’s Fair to boisterous life, with its 228 acres of exotic pavilions, restaurants and theaters, its immense Galerie des Machines, its Javanese dancers and Egyptian souk. A treat for history-loving Francophiles, Eiffel’s Tower is an engaging and exhilarating plunge into Belle Epoque Paris.

Eiffel’s Tower: And the World’s Fair Where Buffalo Bill Beguiled Paris, the Artists Quarreled, and Thomas Edison Became a Count, by Jill Jonnes. Viking, 2009.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email