The Spicy Whites of Alsace

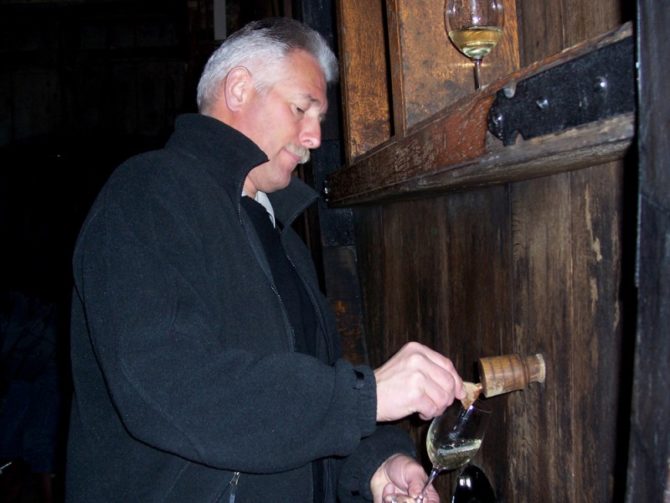

At the Domaine Zind-Humbrecht in Turckheim last summer, owner Olivier Humbrecht invited me to a lunch of homemade meat pie and salad with sweet, succulent tomatoes straight from his garden: “They’re a sign of the 2009 vintage, with good grape ripening as well,” he remarked. He served a 1986 riesling from Rangen, one of Alsace’s 51 grands crus vineyards. Among some 37,000 acres of vines, Rangen is Alsace’s most elevated, at nearly 1,500 ft, and the mountain climate and strong valley winds add to the late-ripening character of the volcanic soil. At over 20 years of age, the wine exuded perfumed beeswax aromas and flavors, with subtle notes of gunflint and tobacco, typical of aged riesling. Alsace’s star grape, riesling easily rivals Burgundy’s chardonnay for character, flavor intensity and longevity.

Most French wines are named after their location, such as Graves or Meursault, honoring their specific terroir. In Alsace, wines are traditionally named after the grape varietal, and their labels mention the location only secondarily, if at all. But Alsatian wine varies with the terroir just as much as Burgundy or Bordeaux. Take rieslings from two famous grands crus terroirs: Furstentum and Schlossberg. The 200-acre Schlossberg was the first Alsace vineyard to be declared a grand cru (in 1975) and its warm, south-facing granite hill makes for good drainage. Furstentum, on the other hand, includes moist clay, resulting in a longer ripening period and fuller bodied wines. At Domaine Paul Blanck in Kientzheim, Schlossberg Riesling 2002, an excellent vintage, exuded smoke, mineral and lime aromas preceding a brisk attack on the palate with apricot and a hint of rose, followed by green apple on the finish — a dry, crispy riesling, perfect for moules frites. The Furstentum Grand Cru Riesling 2002 proved sweeter and richer, with a broader attack of pear, apricot and floral notes, and more orange than lime on the citrus spectrum. The wine deserves coq à l’orange or, as co-owner Frédéric Blanck suggested, lobster with butter.

Alsatian grapes themselves also display varying personalities. In line after the refined and elegant riesling, the region’s two other famous varietals are pinot gris and gewurztraminer. Alsatian pinot gris wine, unlike its Italian incarnation pinot grigio, is rich and full-bodied. It is sometimes compared to Meursault in Burgundy, but I disagree, because it conveys a rich, rather sweet and uniquely Alsatian aspect.

The singularly spicy gewurztraminer, when at its best, exudes complex aromas of cinnamon, nutmeg, faded rose and ginger — a beguiling wine. Be sure you find gewurztraminer from a good producer, however. At its worst — when winemakers ferment diluted yields, for example — gewurztraminer can smell like old geraniums or, worse, cough medicine.

Some of the so-called “lesser” varietals of Alsace are also well worth trying. Muscat, for example, may be the only grape variety that produces a wine that actually tastes like grapes. One of my most memorable experiences was a lunch several years ago at Domaine Weinbach in Kaysersberg. Weinbach muscat is among the best in Alsace, and co-owner and winemaker Laurence Faller served it with asparagus — a daring move because the grassy flavor of asparagus makes many wines taste vegetal and green. But the freshly dry and aromatic Weinbach muscat worked wonders.

Other notable Alsatian varieties are pinot blanc and sylvaner. Pinot blanc produces a round, soft and refreshing wine known for its white fruit flavors — a perfect aperitif wine, although it can also accompany seafood and fish. The underrated sylvaner offers dry, fresh, mineral flavors.

Sweet or dry?

Alsatian wines can be bone dry, but some do include varying levels of residual sugar. Remaining sugar can balance acidity very well — or at least represent the signature of a specific wine style, as in Champagne with brut or demi-sec. It is more common to find some residual sugar in gewurztraminer and pinot gris wines than in riesling, muscat or sylvaner, for example. But the problem for consumers is a dearth of label information about residual sugar. No official labeling differentiates completely dry from off-dry (a term used to indicate only a fleeting hint of sweetness) or even semi-sweet wines. To further complicate matters, there is usually a “house style”. Some producers, such as Trimbach, adhere to a strict, truly dry style. Others such as Zind-Humbrecht, allow for more residual sugar. Many more, including Paul Blanck, Weinbach, Josmeyer and Albert Mann hew to varying degrees of sugar in between. Be sure to ask your retailer or sommelier about the producer’s style: sweet or dry? It’s very important when buying Alsatian wine, and deciding what to eat with it.

Late-harvest harmony

Alsace also produces delicious wines made from grapes harvested as late as November, identified on their labels as vendanges tardives (late harvest) or sélection de grains nobles (selection of noble grapes). Vendanges tardives means wines made with ultra-ripe grapes, with more noticeable residual sugar, sometimes including grapes with noble rot — a benevolent form of a grey fungus known as Botrytis cinerea that dries grapes and concentrates their natural juices, flavors and sugars. Sélection de grains nobles indicates wine made from individually picked grapes all affected by noble rot and containing very high levels of residual sugar, similar to Sauternes in Bordeaux but yielding far different flavors. It is the most expensive of Alsatian wines, made only in certain years and possessing the most intense flavors. Both styles have thicker and richer textures, with notable spice elements and concentrated sweetness coming from the noble rot. Combined with enough acidity, the best of these late-harvest wines achieve pristine balance, spiciness, and focused fruit aromas and flavors, providing a perfectly opulent match for rich, salty or spicy foods, from Roquefort cheese and foie gras to spicy Asian cuisine. A vendanges tardives pinot gris served with duck breast with ginger sauce and exotic fruit would be a perfect match, for example.

Europe’s crossroads

Along the 105-mile wine route south from Strasbourg towards Colmar, one enchanting village follows another, ensconced in vine-filled valleys. Half-timbered houses surround churches, often with German inscriptions. All along the way, be sure to enjoy, as well as the wines, the local cheeses, cuisine, and the Alsatian arts and crafts, such as Beauvillé, a leading supplier of fine handmade tablecloths, napkins, and household linen, located not far from the celebrated Domaine Trimbach.

Wherever you go, you will notice that the names of the terroirs, the grapes and villages often sound more German than French, from riesling and gewurztraminer to Altenberg de Bergbieten and Molsheim. It is no accident that the name Alsace itself is derived from the Latin ali meaning strangers, and Säss, Old German for settlers. During the Middle Ages, Alsace was linked to the Germanic Holy Roman Empire, and Alsatian, a Germanic dialect, was the official language.

Winegrowing in Alsace reached a peak in the 16th century, but the period of prosperity was cut short by the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), which devastated the region. After the war, Alsace was ceded to France, making it French for the first time, but it would remain a disputed territory for the next 300 years, changing hands between France and Germany four times before reverting to France at the end of World War II. Many sites along the wine route, including the magnificent castle of Haut Koenigsbourg, are reminders of the turbulent and complex history of this region on the Rhine.

Strasbourg today is billed as “the crossroads of Europe” and symbolizes the Franco-German friendship of our era. But even in 2010, French wine neophytes — and many French people living outside Alsace — remain perplexed by the less-than-Gallic wine names. Alsace’s long “flute” bottles also resemble German wine bottles, and varietal names like riesling and gewurztraminer (gewürztraminer in Germany) are shared across the Rhine.

The primary difference once was that Alsatian wines tended to be fermented all the way through, resulting in drier wines with slightly higher alcohol than their German counterparts. Many German wine regions have less sun than Alsace, so the German wines are sometimes left with more residual sugar to offset their naturally higher acidity levels. But in recent years, German wine producers have begun to ferment their wines all the way through too, and it’s not as easy as it once was to distinguish between German and Alsatian wines.

The Label Debate

Until March 2005, all Alsatian grand cru wines were required to list grape variety on the label. Since that date, the French wine authority INAO has given Alsace producers the option of indicating the varietal or not. The aim, some say, is to make Alsatian wines “more French” by using terroir names on labels. Worried vintners are convinced that the next move will be to make varietal labeling illegal: a “catastrophe”, they say. An open letter signed by 200 vintners this past summer warned the Association des Viticulteurs d’Alsace (AVA) that such reform would confuse consumers. “It goes without saying that indicating the varietal brings essential comprehension to the consumer,” the letter said. “The future of Alsatian viticulture is at stake.”

Retailers seem to agree. “I would be lost,” said Jean-Frédéric Eckert of Au Millésime, a Strasbourg-based retailer. “Both the grape and the terroir are equally important for Alsace, and especially important for buyers,” he said. For Simon Lambert, wine buyer for American importer The Chicago Wine Company, any such reform would “kill Alsace stone dead”. For the moment, the question remains moot — vintners have the choice in labeling, and no official changes have been proposed.

Panos Kakaviatos writes regularly on wine. Visit his website.

Originally published in the January 2010 issue of France Today.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email