The Man from Madiran

At first glance there’s nothing remarkable about the vast chai at Château Montus where Alain Brumont’s wines lie quietly maturing in row upon row of oak barrels. But then it hits you. Or rather it doesn’t: the musky aroma that permeates most wine cellars is absent. Brumont’s chai is as aseptic as a hospital ward. The polished granite floor is so clean you could serve a hearty Gascon meal on it. That’s the way Brumont likes his chai because the squeaky clean conditions allow for the minimal use of sulfur, the winemaker’s traditional—and ubiquitous— disinfectant. This in turn makes for purer wines, which is precisely the goal of purist Brumont, one of France’s most driven winemakers and certainly one of its most talented.

In his seminal work The New France (a must for oenophiles), wine writer Andrew Jefford has described Brumont as the Citizen Kane of the French wine world. Ambitious, irascible and disputatious (he famously fell out with his own father), Brumont is a single-minded perfectionist who can be conventional when necessary, but is more often highly innovative, exploring any avenue to improve his wines with an energy that belies his 65 years. He needs every ounce of innovation and energy he can muster because Brumont has chosen, as the instrument of his perfectionist zeal, the obscure tannat grape, a black beauty native to the Madiran region of southwest France but notoriously headstrong and powerful.

But 30 years after throwing down the gauntlet as a winemaker Brumont has tamed the tannat and in the process almost singlehandedly transformed Madiran into one of France’s most cutting-edge wine-producing regions. Brumont’s wines, notes wine guru Robert Parker, are “purely made, remarkably rich, and so complete and promising that they cannot be ignored.” Adds wine columnist Steven Spurrier: “The wines of Alain Brumont are at the same level as Château Latour and the greatest wines in the world.”

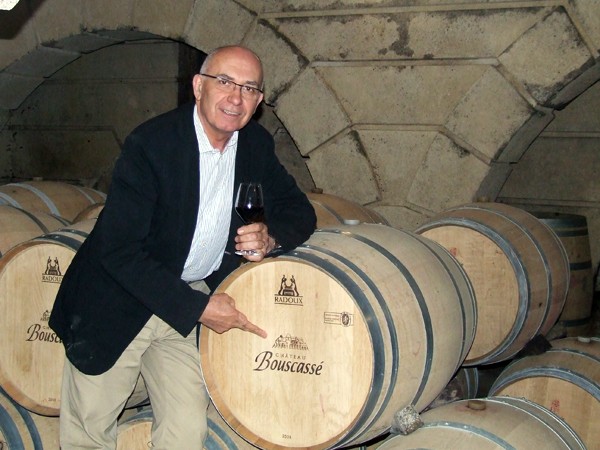

The making of Madiran has been a slow process, but nobody who knows Brumont and his dedication—some would say ruthlessness— could be surprised by what he has achieved. Locals note that the best terroir for vines in Madiran is found on some 22 hills and ridges spread across the appellation. Down the years they have watched with admiration and not a little envy and concern as Brumont has enriched and extended his two main properties—Château Montus and the original family winery Château Bouscassé—by patiently and methodically acquiring land and planting vines on all but two of these uplands. “The best wine comes from the best terroir,” Brumont explains. “And the best place to make high-quality wines is high up the slopes.”

It took years of waiting for Brumont to acquire the south-facing hillside vineyard known as La Tyre, but when the 25-acre parcel became available in 1988 he snapped it up, producing his first single-vineyard wine from the property in 2000. Seven years later a jury of wine experts convened at Montus for a blind tasting that pitted Brumont’s super-premium, 100%-tannat La Tyre against some of the world’s finest wines, including Château Mouton Rothschild, the legendary Bordeaux grand cru. The result? La Tyre was ranked third, just ahead of stablemate Château Montus Cuvée Prestige. Both of Brumont’s wines topped the Mouton, which says a lot for his winemaking skills. But here’s the best thing about La Tyre: a case of the 2009 vintage en primeur will cost you $650 (excluding taxes and duties); a case of 2009 Mouton Rothschild is currently selling en primeur for around $13,000.

In nearby Bordeaux, the 2009 claret vintage has already been declared a great year by the wine cognoscenti (which helps explain the eye-watering price for the Mouton Rothschild). But although the jury is still out when it comes to Madiran, Brumont—no slouch when it comes to singing his region’s praises—insists that last year’s vintage should “reach heights comparable with the greatest vintages of the past 30 years.” It could, he predicts, “dethrone the legendary 1985, 1990 and 1992 vintages.”

Brave words indeed, but a recent barrel tasting of Brumont’s 2009 wines en primeur at Montus confirmed that the man from Madiran has excelled himself yet again. All Madiran appellation red wines must contain at least 40% tannat, an appropriate name for a grape so tannic and mouth-puckering that Madiran has traditionally been rendered drinkable only by diluting it with other wines, lengthy cellaring or, in recent years, through a widely used micro-oxygenation process which softens the tannins by exposing them to minute and controlled amounts of oxygen during the vinification process.

The Black Wines

Ever the contrarian, Brumont declines to employ micro-oxygenation, yet his oneyear- old wines are silky smooth and will be eminently drinkable by the time they are bottled and shipped in about a year. That’s not to say that the 2009s shouldn’t be allowed some time to mature. Good Madiran, like good Bordeaux, can benefit from a decade or so in the cellar, and some only begins to hit its stride after two decades. But if you can’t wait to taste what Brumont has released just reach for the corkscrew (and the decanter) whenever you feel like it and his wines are guaranteed to be drinkerfriendly. Health-friendly too (of course in moderation): the antioxidant polyphenols which mop up cell-damaging free radicals in the blood are what accounts for the socalled French Paradox and according to wine researchers, the tannat grape contains more of these beneficial polyphenols than most others—which might help to explain why tannat-swigging Gascons have the longest life expectancy in Europe, notwithstanding their consumption of vast quantities of foie gras, goose fat and other artery-clogging local specialties.

If Brumont’s wines are now challenging Bordeaux’s finest in terms of quality it is only history coming full circle to demonstrate that natural justice is still a force. After Julius Caesar conquered ancient Gaul, the Romans colonized the southwest region for its timber and for its temperate, wine-friendly climate. In the Middle Ages, Madiran and its neighbor Saint-Mont, together with Gaillac and Cahors to the northeast, belonged to the region known as Gascony, forming the region’s interior Haut Pays, or high country, which became famous for its so-called “black wines”. Back then these ink-dark wines, made with Madiran’s tannat grapes and malbec or auxerrois from Cahors, were often mixed with lighter Bordeaux to produce robust blends that traveled well to the wealthy regions of northern Europe, where they were highly prized by a society slowly emerging from the Dark Ages and fast acquiring a taste for the good things in life.

The Bordelais, who controlled Atlantic transport routes (and retain a hard-nosed reputation to this day) made great efforts to blunt the commercial prospects of the landlocked black wine producers, saddling them with tariffs and other trade barriers. But you can’t keep a good wine down and Gascony’s black blockbusters remained so popular that output from the Haut Pays rivaled that of Bordeaux well into the mid-19th century. Then France was struck by phylloxera, the aphid-borne blight that devastated Europe’s vineyards in the 1870s. Richer regions like Bordeaux and Burgundy were able to survive and recover; the black wine producers of poorer Gascony were dealt a knockout blow. Few vineyards were replanted as peasants left the countryside for the new cities of the industrial revolution or emigrated to the New World. Traditions and winemaking skills, even grape varieties, were lost. By the end of World War II southwestern winegrowers were an endangered species. Most of Madiran’s vineyards were ploughed under, and the venerable tannat grape began what promised to be a swift slide into extinction.

When Brumont was growing up, his father Alban was one of the few in Madiran who still produced some wine, although only 40 of his 360 acres were planted with vines. Alain served his wine apprenticeship at the family’s Château Bouscassé, but he soon grew frustrated with what he considered his father’s lack of ambition and headed for Bordeaux to continue his wine education. By 1979, however, he was back in Madiran where he inherited 40 or so acres at Bouscassé and began to build the foundations of a local wine empire that would eventually encompass over a tenth of the Madiran appellation. Château Montus, badly run down, was acquired the following year, coinciding, Brumont recalls, with an epiphany in which he realized that the tannat grape had world-class potential.

Green Harvest

It was an epiphany that set him on a long and winding road that nearly became a dead end on several occasions. He replanted all the vines at Montus, but in 1985 his first attempt to make a 100% tannat wine was not well received by the guardians of the Madiran AOC. They reminded him that the rules—devised in an era when 100% tannat wines were undrinkable—said his wines had to be blended with the likes of cabernet sauvignon and merlot to qualify for AOC status. Brumont appealed to a higher wine authority who judged his new offering—dubbed the cuvée prestige—the star of the region.

His acquisition of Montus was nearly stymied when the local bank, where his father was on the board, refused to supply the credit he needed. He eventually raised the money elsewhere, but the next 20 years were a financial roller coaster as his ambitions threatened to outstrip his ability to finance them. A vast makeover of Montus in the 1990s, which transformed the château into a five-star hotel and built the huge chai that came to be known as the cathedral of tannat almost bankrupted Brumont. Distribution problems in Japan didn’t help, nor did an overly rapid extension of wine styles.

These days Brumont is more cautious. (Well, a bit more cautious—he still skis hard and takes to French country roads on his bicycle, a potentially life-shortening activity.) He now shares decision-making with oenologist Fabrice Dubosc, a fellow Gascon who has been working with Brumont since 2001. Together they are pursuing a strategy of doubling the vine density on the Brumont estates. In an era when most qualityconscious wineries are seeking to reduce grape yields in order to improve quality, that approach seems counterintuitive. But they hear a different drummer: yields are reduced with three “green harvests”—pruning bunches of green grapes before the main harvest—while the closeness of the vines produces a bonsai effect resulting in smaller, more flavorful bunches.

Whatever Brumont is doing, he seems to be doing right. His wines, both red and white (see box), have polish and purity. Thanks to Brumont’s drive and passion, Madiran is once again a star in the oenological firmament. It is not in Brumont’s nature to expect thanks for what he has done for French regional wines; being acknowledged as one of the finest of winemakers seems reward enough for him. But wine lovers should say a big merci anyway. With the tannat, a black beauty is back.

NOTEBOOK

Alain Brumont’s twin flagships are the Madiran AOC wines Château Bouscassé and Château Montus. He also makes a range of well-reviewed everyday drinking wines with the appellation Vin de Pays des Côtes de Gascogne.

Château Bouscassé

The original family domain produces three main cuvées, two reds and a white:

Vieilles Vignes (100% tannat) Château Bouscassé’s premium wine comes from old vines, some of which are 75-year-olds. The Vieilles Vignes wine spends 14–16 months in new oak barrels.

Château Bouscassé (60% tannat, 20% cabernet sauvignon, 20% cabernet franc) A traditional Madiran blend, with all three components working in harmony.

Pacherenc du Vic Bilh Doux Difficult to pronounce, this sweet white (100% petit manseng) is easy to fall for.

Château Montus

The center of Brumont’s winemaking empire, with three reds and one white:

La Tyre (100% tannat) Wonderfully balanced, it’s a single-vineyard wine, aged in new barrels. Gets better, if that’s possible, after a decade or so in the cellar.

Cuvée Prestige (100% tannat) La Tyre’s stablemate can often give it a run for the money. Deep intense color, dark cherry fruit. Be patient.

Château Montus (tannat and cabernet sauvignon) Hints of red berries, lots of finesse.

Pacherenc du Vic Bilh Sec (80% petit courbu and 20% petit manseng) A full-bodied dry white wine, an award winner and a favorite with Robert Parker.

And also:

Château de Perron (tannat/cabernet franc) A new addition to the domain, with a spicy aftertaste.

Château Laroche-Brumont l’Eglise (tannat/cabernet franc) A new wine with a lot of promise.

Le Pinot Noir d’Alain Brumont (tannat/ pinot noir) A recreation of an 18th-century- style Madiran, made in limited quantities. Now into its second year, this wine from the past has a great future.

Originally published in the September 2010 issue of France Today.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email