What the Nose Knows

The art of perfume-making is as complex and mysterious as the world of winemaking. Lanie Goodman sniffs out some of the best noses in the business to find out more about the world of scents.

Imagine a woody smell so rich in nuances that you hesitate between smoky, sweet and earthy, with a glowing freshness that hints at notes of leather and velvety spices; inexplicably, one drop of this intoxicating musky aroma will stay on the skin, long after most others evaporate. This is one way to describe oud, one of the world’s most expensive raw scent ingredients, often called liquid gold, that comes from a Southeast Asian agarwood tree and sells for as much as $50,000 per kilogram.

Oud is rare, only produced when the tree becomes infected with a parasitic mould and oozes a dark, gummy, strongly scented resin. The sap’s pungent odour is, at best, “animalistic” (some might say, revoltingly fecal), yet that same nasty smell will take you to olfactory paradise, once expertly blended with other exotic ingredients – rose, sandalwood, cardamom, Tonka bean, vanilla or amber. And then, lo and behold, a best-selling perfume is born.

But of course, it’s not that simple. The creation of unique fragrances is a complex and secretive process that can take years. You need all the finest raw materials, a place with sundrenched fields full of meticulously tended flowers – which is one reason why Grasse in the Alpes-Maritimes, the perfume capital of the world, assembles some of the world’s most celebrated ‘noses’, who work for Hermès, Dior, Vuitton and Chanel. It is also home to small luxury niche perfumers such as the family-run Maison Micallef, whose bejewelled crystal bottles are hand-designed to match their opulent perfumes.

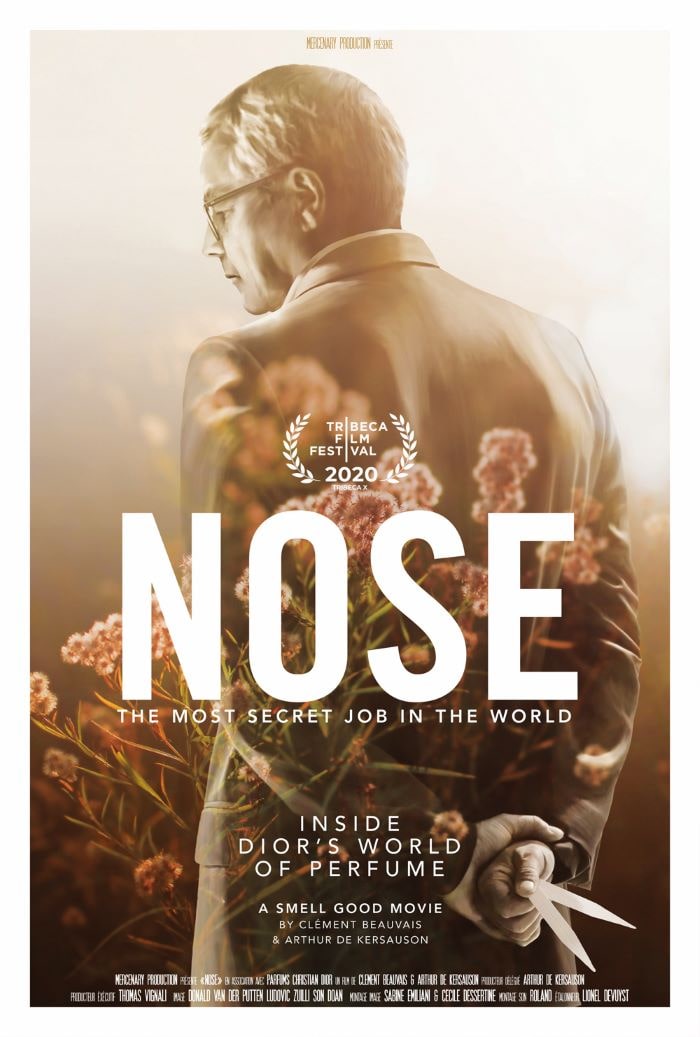

The documentary ‘Nose’ provides a fascinating insight into the world of perfumers. © Clement-Beauvais ‘NOSE’

UNCOMMON SCENTS

Unsurprisingly, among today’s most reputed noses in the industry are locals born into generations of perfume-making families, Grasse’s own enfants du pays.

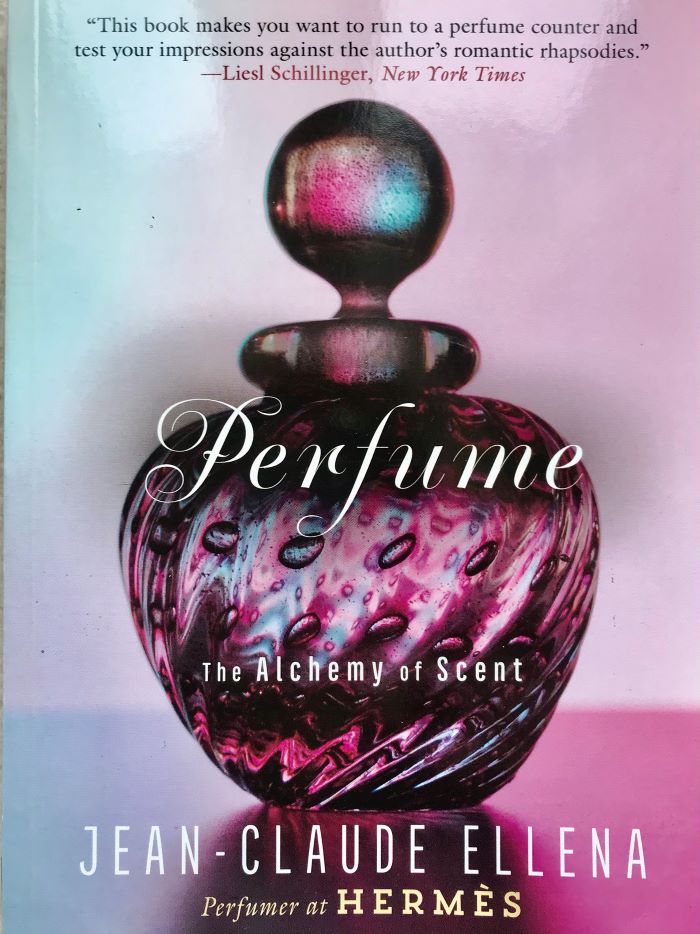

Take, for instance, Jean-Claude Ellena, the former nose for Hermès, whose training started at home at an early age, since his father was a reputed perfumer. By the time Ellena started an apprenticeship at a local perfume factory in 1964 at the age of 17, he had already cultivated a deep memory of odours and an olfactory vocabulary. Both an author on perfume and fragrance consultant, Ellena’s approach has always been poetic. Inspiration, he says, might unexpectedly strike when a young girl tears off a fig leaf and holds it to her nose – that ephemeral moment in a Mediterranean garden would translate in his head to a formula. As Ellena explains in his book, Perfume, the Alchemy of Scent, some of the world’s finest raw materials – extracts from flowers, fruits, leaves, barks, woods, resins, seeds and roots – are still exported from remotes corners of the globe. Others, which include animal material such as musk, have been replaced by chemical reconstructions.

Synthetic materials are molecules identical in structure to the natural molecules, he says, and are often single compounds that resemble natural odours and are easy to use. By combining two synthetics – coconut oil and mint – when superimposed on a blotter, the smell is exactly like a fresh ripe fig. “I can conjure it in just two molecules, even if a real fig has 400. It’s that simple and that difficult.”

With the recently-released documentary Nose, directed by Arthur de Kersauson and Clément Beauvais (available on Amazon Prime and other platforms), the spotlight is currently on another star nose, François Demachy, who teamed up with Dior in 2006. Born in Grasse, Demachy recounts how the smell of jasmine was an inextricable part of his adolescence.

“People think that you mix some things that smell good and you’ve got a perfume,” he says, noting that there are as many as 1,000 raw materials available today. “It’s not just another product. More than anything, perfume is emotion.”

Perfume by Jean Claude Ellena

But how do you translate the sensation of orange blossoms on a balmy summer night? You can’t quantify what makes a great fragrance but the film brings you closer to how that is done, Demachy says, by endlessly readjusting formulas, or asking your wife to test wear your latest creation. What is the Dior nose’s favourite scent? “White or grey amber”, he says. “It is sweetly beautiful, not in-your-face.”

Highlights of the film also include a glimpse at a voyage to Indonesia in search of patchouli. We see Demachy wandering through souks, sniffing spices in jute bags or putting his precious talents to work at the Château Cheval Blanc Winery, where he is a consultant. No need to swirl or sip: a simple whiff of Merlot is enough to detect notes of green pepper or prunes.

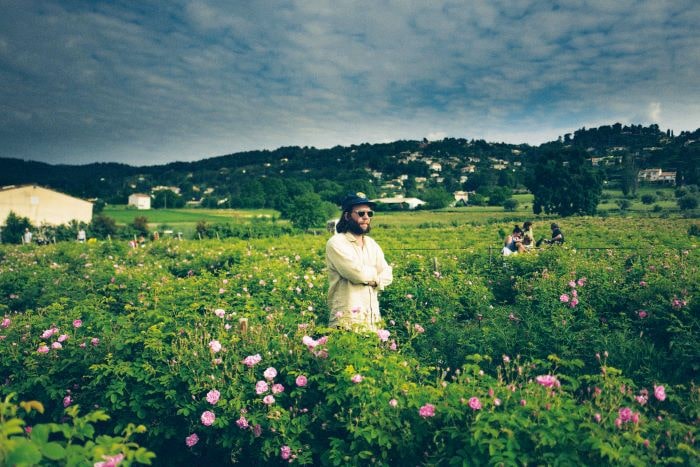

The most interesting scenes are shot at Demachy’s native turf in Grasse where he drops in on “the queen of flowers”, Carole Biancalana, whose exceptional jasmine and May roses at le Domaine de Manon are known throughout the world. While chatting with longtime Grasse-born colleague Jacques Cavallier-Belletrud (who is the star nose for Vuitton), their philosophical discussions tend to be brief: a perfumer is, above all, “a man who is curious about everything,” muses Cavallier-Belletrud.

“Perfume-making is like gastronomy,” says Grassebased chemist, Ivan Coste-Manière, who, throughout his career, has collaborated with big-name perfume houses including Van Cleef, Yves Saint Laurent and Dior. “You’ve got the nose – the star chef – who tastes the sauces and puts the final touch to his recipes, but there’s also a brigade of cooks behind him, the chemists who deal with the technology of distillation and extraction of the raw materials, plus the farmers. It all goes back to the earth.”

A still from the documentary ‘Nose.’ © ‘NOSE’

OLFACTORY OUTINGS

As a “molecule man” and CNRS scientist, Coste-Manière has done just about everything from inventing a smell to give cattle a hearty appetite to devising kitty litter that emits a cassis berry aroma when the cat urinates on it. But perfume is his passion, which doesn’t mean that he locked himself away in a lab, experimenting with synthesised substances. “You can also do it, naturally and totally organically and ecologically, with cells and enzymes.” Coste-Manière travels widely, “to be closer to the raw material that you can’t find anywhere else. Right now, I’m working on bergamot from the Ivory Coast. which has always been considered to be better than Sicily.” After replanting and upgrading the crops, he explains, you find bergamot with the same citrusy notes as legendary classics like Eau Sauvage. (Like Ellena, his mentor is Edmond Roudnitska, who created Dior’s Eau Sauvage in the 1960s and pioneered minimalist formulae).

“That’s what’s fabulous about luxury perfume,” Coste-Manière says with a grin. “You can take an idea that is 50 years old and reinstate it. You find the same intelligence, nobility and the efficacity of those who mastered it. Those guys had no computer but were capable of getting the smell they wanted. The genius lies in the craftsmanship – the real know-how is having a tool in your head to be able to make what you want.

“I went to Egypt because the jasmine has to be picked at four in the morning,” Coste-Manière continues. “The jasmine flower changes contents and odour in terms of the UV rays, so as soon as the sun rises, of course, you’ll still have jasmine, but it won’t have the same smell. Which allows you to work on a head note that is maybe a bit more elaborate, a longer trail, because we work with the circadian rhythms of plants. The closer you are to an extraction, you will also prevent the plant from making its own enzymes, which kills the odour. If you pick a tomato off a vine or leave it two days in the fridge, it’s not going to have the same smell.”

Carole Biancalana grows renowned jasmine and May roses at le Domaine de Manon. © ‘NOSE’

A TREASURE TROVE OF SCENTS

Far from the pressures and marketing trends of the industry, artist Martine Micallef and her husband, former financer and self-taught perfumer Geoffrey Nejman, founded the exclusive “ethnic niche” fragrance company M. Micallef in 1996. With headquarters in Grasse – a factory, boutique, plus their own jasmine fields – M. Micallef is distributed in more than 75 countries.

They distinguish themselves from other companies with a refined mix of precious oils and European and Middle Eastern scents in stunning hand-painted flasks, adorned with gold leaf and semi-precious stones and crystals. “I wanted to restore crystal art, just as François Coty asked René Lalique to embellish his bottles,” says Martine, a passionate art lover and painter who grew up in Saint-Paul de Vence. “My husband Geoffrey and I are both autodidacts and have no pretentions about comparing ourselves to the great noses of our profession. We create our fragrances to give pleasure.”

The couple’s initial inspiration may also vary. “Either I have an idea for the bottle and I tell Geoffrey, ‘you should find a perfume for this’”, Micallef says, “or we sit at a round table and I explain my concept to a group of young perfumers and our official nose, Jean-Claude Astier. They each create a formula and the voyage begins… Unlike the big brands, we’re not in any rush. We keep adjusting the dosages, a process which often goes on for more than a year.”

Micallef describes her latest addition to the Jewel Collection, Eden Falls, like a burst of impressionistic poetry. “We’re in the undergrowth, the woods, I want to smell moss, with the sensuality of patchouli, plus a turquoise pool and fresh grey foamy splashes, a spray of the waterfall on your body.”

One whiff will convince you: I spritzed myself with the sample that Martine kindly sent my way and was plunged into a fairytale sun-dappled forest where glittery-haired water nymphs frolic under a cascade. Immediate bewitchment guaranteed – the language of perfume needs no translation.

- M. Micallef’s glass bottles are as beautifully made as their perfumes. © M MICALLEF

- Martine Micallef

- Industry veteran Ivan Coste-Manière. © WIKIMEDIA

- The scent of jasmine changes with the sun. © M MICALLEF

- Author Jean-Claude Ellena. © WIKIMEDIA

- © ‘NOSE’

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in perfume, perfume in France, perfume making, Review

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *