The Artist: Cinema Love Song

It was one of the most unlikely movie events of the year. Presented at the Cannes film festival last May, The Artist met with thunderous applause and ecstatic reviews. Actor Jean Dujardin, excellent in the role of declining movie star George Valentin, won the César award for Best Actor, and eventually more than a million and a half people saw the film in France. But no one expected the low-budget, black-and-white, silent movie to seduce American critics and film lovers too—Time called it “the fizziest, most endearing movie in ages”—making it a strong contender for the upcoming Academy Awards.

Such a glorious international destiny is actually pretty rare for a French film. No French production has ever won Hollywood’s Best Picture award. The Franco-Polish Roman Polanski is the only Academy-anointed Best Director, for The Pianist in 2003. And although Marion Cotillard won Best Actress in 2008, for her role as Edith Piaf in La Môme (La Vie en Rose), and Simone Signoret won in 1960 for Room at the Top, no French actor has ever won an Oscar.

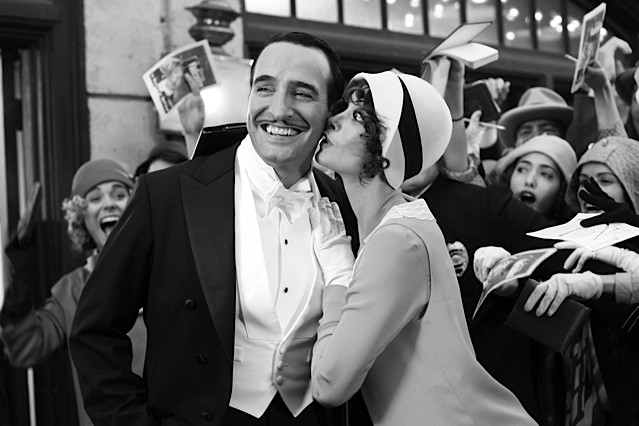

Jean Dujardin as George Valentin. Credit © La Petite Reine/Studio 37/La Classe Américaine/JD Prod France 3 Cinéma/Jouror Productions/uFilm

But writer/director Michel Hazanavicius’s The Artist is indisputably different from its predecessors: it’s black and white, shot on real color film, not digital, and then converted; and it’s silent, with all the dialogue on title cards except for a single two-word spoken phrase, and accompanied by a lush musical score. It’s also shot at a slightly different speed, closer to that of early cinema, to reinforce the silent-movie effect.

Its unexpected success doesn’t seem so implausible when its roots in the long history of American cinema are considered. “The story of the movie is pretty classic, with solid archetypes directly drawn from Hollywood productions,” says film critic and scholar Baptiste Liger. “The rise and fall of its main protagonist, the success story of the young woman, the love relationship between them—all these themes are pretty usual. They’re just adapted to a different set and era.”

Known in France first for his comic roles on TV and then for the OSS 117 spy-spoof movies, in The Artist Dujardin radiates old-fashioned movie-star charm. (See Dujardin interview, France Today January 2012.) Playing a silent film star named George Valentin—a nod to icon Rudolph Valentino—Dujardin displays an impressive physique, mixing Gene Kelly’s sunshine smile with the pencil-thin mustache and swashbuckling style of Douglas Fairbanks. In an excerpt from one of Valentin’s action-hero films, he dons the mask of Zorro—one of Fairbanks’s signature roles.

Playing opposite him, Bérénice Bejo—director Hazanavicius’s wife—is the irresistible ingénue Peppy Miller, a young flapper whose costumes and manners seem inspired by 1920s stars including Louise Brooks and Clara Bow. (For those who like to follow circuitous clues, the small role of Valentin’s wife is played by American actress Penelope Ann Miller.)

Bérénice Bejo as Peppy Miller. Credit © Wild Bunch 2011

Star-crossed paths

The screenplay pays homage to later Hollywood classics too, starting with Singin’ in the Rain. That 1952 Stanley Donen movie also chronicled the transition from silent film to “talkies”, starring Gene Kelly as a popular silent film star and Debbie Reynolds as a promising young actress. “Singin’ in the Rain is an essential standard for this genre of movies,” says Liger. “It would be hard not to wink at it. Several references are to be found in The Artist, including the glorious movie premiere at the beginning and the dancing finale.” In one scene, Peppy Miller wears an almost-exact copy of a Debbie Reynolds dress.

The crossed paths of a declining idol and a rising starlet are also at the core of William Wellman’s 1937 A Star is Born, starring Janet Gaynor and Frederick March (remade in 1954 with Judy Garland and James Mason, and again in 1976 with Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson). In that impressive drama, though, the romance between star and starlet is doomed by jealousy, resentment and alcohol. Even Sunset Boulevard, by director Billy Wilder, could be referred to, with its cruel outlook on Hollywood and its often incompatible goals—art and profit.

Small winks at classics

In addition to the fairly obvious influences, The Artist is also filled with more subtle tributes, although recognizable to most movie buffs. Valentin’s breakfast with his angry wife looks very much like breakfast in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941), where Kane sees his marriage falling to shreds. Kane pops up again in a later scene, when a washed-up Valentin contemplates his useless belongings.

Scenes with his faithful hound, played by the extraordinary Jack Russell terrier Uggie, could be in homage to silent-film comedian Max Linder (born Gabriel Leuvielle, near Bordeaux), or to Charlie Chaplin, whose City Lights and Limelight are also quoted.

“The Artist is stuffed with small winks at old classic movies many people have never seen,” says Liger. “There are a few details that are hard to get, but it is quite exhilarating to watch the movie like a treasure hunt. A complex staircase, for example, is borrowed from Sergei Eisenstein. Several views of the city come from Friedrich Murnau’s Sunrise, and George Valentin’s nightmarish visions from Murnau’s The Last Laugh.”

There are also several references to King Vidor’s The Crowd, and to Frank Borzage movies, including the superb scene when Peppy Miller, alone in Valentin’s dressing room, slips her arm through Valentin’s jacket, inspired by a similar scene with Janet Gaynor in Borzage’s Seventh Heaven.

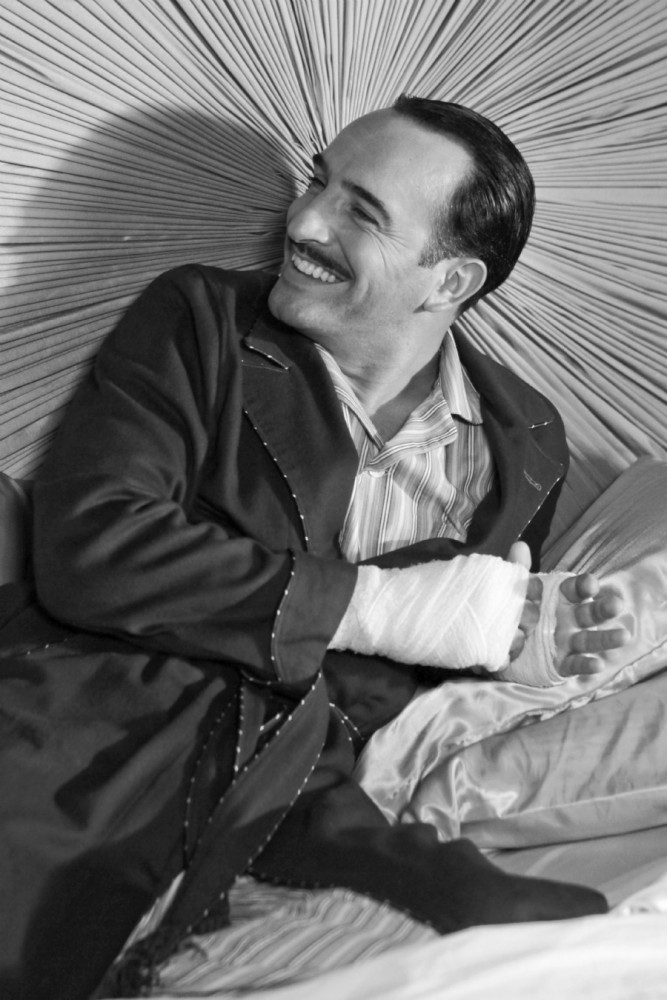

Jean Dujardin in The Artist. Credit © Wild Bunch 2011

Postmodern love song

Even the musical score, by composer Ludovic Bource, might seem very familiar to movie-goers, with its snatches from Leonard Bernstein and Alfred Newman. “It sounds very naive,” adds Liger, “maybe even more so than the scores played at the time. But it is done on purpose, that’s for sure. Near the end, when Valentinis on the verge of suicide, you can hear something very close to Bernard Herrmann’s romantic score for Vertigo. It’s one more example of revisiting Hollywood history.”

But while The Artist pays homage to the classics, especially silent films of the 1920s, it should not be mistaken for one. “First of all, it is not a real silent movie,” says Liger, “since you can hear a few sound effects. It’s an enactment of a silent movie, only watchable thanks to a pact with the audience. It’s a bit like watching Back to the Future: you can create an extra-naive world because people are aware of what has become of the world and the cinema.” Less a plain pastiche than a true postmodern film, The Artist is a declaration of love to a long-gone epoch, not unlike Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, a tribute to pioneer French filmmaker Georges Méliès that is also an Oscar contender this year. “Directors in the 1920s didn’t consider themselves pure artists,” notes Liger, “but more as makers of some sort. That’s something Michel Hazanavicius admires, and tried to replicate in this movie. In a larger sense, it’s less The Artist than ‘The Artisan’.”

Originally published in the February 2012 issue of France Today

Jean Dujardin and Bérénice Bejo in The Artist. Credit © Peter Lovino / La Petite Reine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *