Pétanque: Life in the Slow Lane

It’s as Provençal as cicadas and pastis, but this variation of the ancient game of bowls is now played far beyond France’s borders and is even bidding for Olympic status. Dominic Bliss explains its enduring appeal

The loud, sharp clack of steel boule on steel boule. Anyone who has been to the south of France knows that distinctive sound. Along with the susurration of cicadas, it’s part of the aural backdrop of the Midi. Is there anything more emblematic of French leisure time than pétanque?

For we Brits, boules – and particularly the Provençal version of the game, pétanque – is often our very first foray into the rich world of French competitive sport. As tourists, it’s likely we’ll share a game with locals in a village car park long before we experience any of France’s myriad other sports.

That was certainly the case with me. I remember being in a campsite somewhere in Provence, aged six or seven, trying my hardest to apply topspin by flicking my wrist upwards. We were playing with one of those tacky multi-coloured sets of boules designed for beach use. Several ended up rolling beneath the tent of a distinctly vexed German family.

The game of pétanque. Photo credit: Fotolia

But the rules of the game were so beautifully simple, even for a child: you stand in a circle (or behind a line toed into the dirt) and attempt to get your boules closest to the wooden jack (le cochonnet); each winning boule wins a point; 13 points wins a game.

My next venture was a decade later while on a student exchange trip in Brittany. My French counterpart and I didn’t get on so well, meaning that I had plenty of time to play pétanque with his sisters. I was a keen pupil, they were forgiving teachers, and my skills came on in leaps and bounds.

Fast forward to the late 1980s when my parents were flirting with the idea of buying a house in the Var. We spent a couple of summer holidays down there, in a village called Aups, where my brother and I spent every evening quaffing Kronenbourg 1664 and cheap rosé with young locals. There was just the one bar in the village, so after last orders we would set up a makeshift boulodrome in the adjacent car park and we’d throw steel until the early hours. It was here that I learned that you could play singles, doubles, or even triples.

My most memorable boules endeavour of all was in the early 2000s while on a driving holiday with two friends in Auvergne. We found ourselves in a small town (whose name now escapes me), where our hotel manager invited us to play a version called boule lyonnaise. He and his friends were serious league players, and they gave up their Sunday morning to teach us the complexities of their sport inside a huge indoor boulodrome. The game is similar to pétanque, except that the balls are slightly larger and heavier, and you launch your throw with a vigorous run-up.

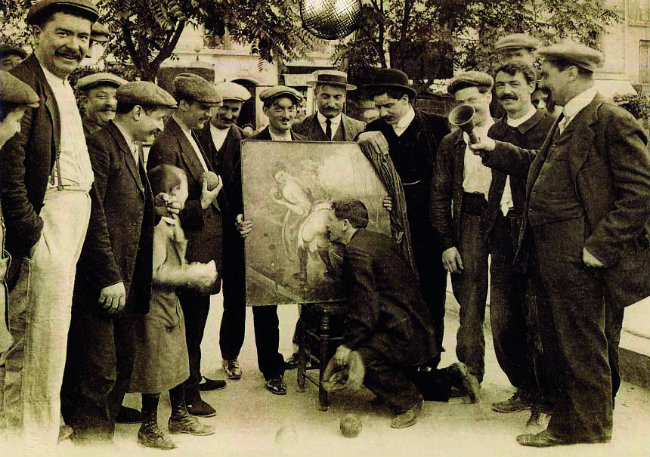

The modern game dates back to the turn of the 20th century. Vintage postcard: Alamy

Boules, and particularly pétanque, is enormously popular all over France and her territories. It may not have the dynamic impact of the Tour de France or Roland-Garros, or top-level football and rugby, but in terms of the number of regular players it’s a cornerstone of French sporting culture.

According to the Fédération Française de Pétanque et Jeu Provençal, established in 1945, there are now more than 6,200 registered clubs and 300,000 registered players across France. At the sport’s highest level there’s a national league, culminating in the Championnat and Coupe de France. The federation claims that boules is the nation’s number one non-Olympic sport.

How on Earth has this village pastime become so pervasive across French society? Although bowling games trace their origins to ancient times, the modern game we recognise as pétanque dates back to 1907. It all started in the Provence town of La Ciotat with Jules Lenoir, a boule lyonnaise player. So afflicted was he by rheumatism that he couldn’t manage the traditional run-up before the throw. A friend decided to help him out by developing a new variant of the game which required players to throw with both feet planted firmly on the ground. It proved popular and quickly spread across the south of France. In the Provençal language they called it pèd tanco (fixed foot), which quickly evolved into the word pétanque.

FRENCH CONVIVIALITY

“What other sport symbolises the French way of life quite so much?” asks Joseph Cantarelli, from the federation. “What other sporting discipline so symbolises French conviviality? What other physical activity brings together so many different types of people by age, profession and social class? It’s pétanque, a sport both for the masses and for the elite, played both for fun and at a top competitive level. Pétanque brings everyone together. And it’s cheap to play.”

Paul Shore is the Canadian author of My Year in Provence Studying Pétanque, Discovering Chagall, Drinking Pastis, and Mangling French. He describes his adopted game as “one of the surviving morsels of French culture”.

“Pétanque is uniquely French,” he writes. “The players tend to be middle-aged to elderly men whose exposure to the sun from playing the game gives them a healthy, light-brown tinge, usually coupled with a skin texture similar to that of a well-aged French prune. These gentlemen seldom speak, and when they do open their mouths, what is heard is usually slang or profanity, or silence followed by a puff of smoke from the drag they took of a cigarette several minutes earlier.

“For the purists, pétanque isn’t played on an organised field but on a small, open patch of grassless ground next to a public gathering place, like a café or a church. The grounds may be anything but uniform in size, shape, and consistency of dirt, and may include any number of obstacles, such as massive plane trees, café terraces, and elderly dogs.”

A game of pétanque taking place in a square in Saint-Tropez. Photo: Flickr

Having spent a whole year studying and perfecting pétanque, Shore is better placed than anyone to analyse the French adoration for this sport. “I believe it became so popular not because it was simple or affordable, rather because it is quietly very social,” he says.

“It brings local people together to share friendship and culture, while giving them a break from their daily work or worries. And the French are wonderfully social, valuing calm time with close friends and family, from deep conversations, sipping coffee, pastis or wine to long, multi-course meals with plenty of discussion, to slow-paced games of pétanque between old friends.

“And I believe this appeal of pétanque crosses all levels of society because the French all love celebrating close family, friends, and the elements of their culture that remain strong.”

SIMPLE TO PLAY, DIFFICULT TO MASTER

Another North American writer, B.W. Putman, has penned a book on the sport. “It’s simple to play, yet difficult to master,” he writes in Pétanque: the Greatest Game You Never Heard Of.

“The strategy is utterly obvious, yet it’s superbly subtle and multi-layered. The equipment is inexpensive and lasts for years; it’s the lowest of low-tech, nothing but a few baseball-sized steel boules. Pétanque is equally accessible to men and women, and the young and old. Granted, forearm and shoulder strength are assets, but a delicate touch and merciless cunning usually vanquishes unbridled brute strength. And forgive me for being indelicate, but a calorically challenged person with a BMI of 35 can directly compete with an ultra-marathoner with five per cent body fat. There’s nothing quite so satisfying than to see a couple of old fat guys despatch a team of young gym-rats with six-packs.”

North America is just one of many regions around the world that has imported this quintessentially Gallic pastime. The international governing body for all boules sports is called the Confédération Mondiale des Sports de Boules, which is based in Monaco. It rather boldly claims to encompass 262 national federations across 165 countries, with close to 200 million players.

And now, on behalf of the three main boules sports – pétanque, boule lyonnaise and the Italian version, raffa volo – it’s lobbying to be included in the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris. “Our goal is ambitious,” they admit.

The main barrier to Olympic inclusion is perhaps the game’s image. Martin Eggleton is president of Pétanque England. He concedes that the stereotype of a superannuated Provençal villager with beret atop head, cigarette clenched between teeth, and glass of pastis in hand has hindered their attempts to be taken seriously by the wider sporting community.

“The challenge we have is that people question whether it’s a sport or a pastime,” he explains. “Most people have this image of the Gauloises-smoking Frenchman playing pétanque with a glass of wine. That’s how it’s often portrayed in posters and advertising.”

Eggleton accepts that this image will always be part of the sport’s culture, but he and his colleagues would like to see it accepted as a true sport. “I use a football analogy to explain it,” he adds.

“You’ve got the World Cup for professional football, but at the grass roots level, you’ve also got jumpers for goalposts in the park. Both are very valid forms of football, but with very different aims.

“It’s the same with pétanque: meeting your friends outside the local bar and having a couple of friendly games and a glass of wine is just as valid as playing in a world championship final.” In Marseille, just a few miles from where pétanque started in 1907, there’s now a museum and shop dedicated to the sport, called the Maison de la Boule. The most numerous items on show are porcelain renditions of a lady’s bottom with the name Fanny written beneath them.

Kissing Fanny, a ritual humiliation enforced upon any player who fails to score a single point in a game

Ever curious, I ask the curator/shopkeeper about the significance of Fanny. He tells me how, years ago, in a southern French village, there was a local lady of supposedly dubious morality who was very keen on pétanque.

“When a team lose a match 13-0, the winners give to the losers a forfeit: you must kiss the arse of Fanny,” he explains in his broken English. And sure enough, nowadays, at boulodromes across Provence you will spot Fanny’s porcelain bottom proudly hung courtside. And, yes, if you lose 13-0, you’d better pucker up, just like in the old days.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY