Open and Shut Case

From utilitarian item to international object of desire: Louis Vuitton, Goyard, and Moynat, uniquely poised at the dawn of fashion and travel, seized a moment in history to transform their trunk making businesses into three of Paris’s most prestigious and enduring luxury brands. Louis Vuitton, now a global fashion giant, Goyard revered by the cognoscenti of chic, and Moynat, an illustrious name restored to its former glory in 2010 – all anticipated the revolution in women’s fashion and participated in the greatest evolution of the 19th and early 20th century: the advent of mass travel. The world begins its hectic pace and Paris is its beating heart.

It was a time like no other: the Industrial Revolution fuels the rise of commerce and urbanisation; Haussmann begins his monumental transformation of Paris, adding the grand boulevards and razing entire neighbourhoods to make room for modern buildings and spacious squares; commerce is booming and the appearance of department stores marks the emergence of mass-produced clothing and the blossoming of fashion for all strata of society, exactly coinciding with the emergence of haute couture. As fashion becomes more accessible, it also becomes more rigidly hierarchical, stratified and codified.

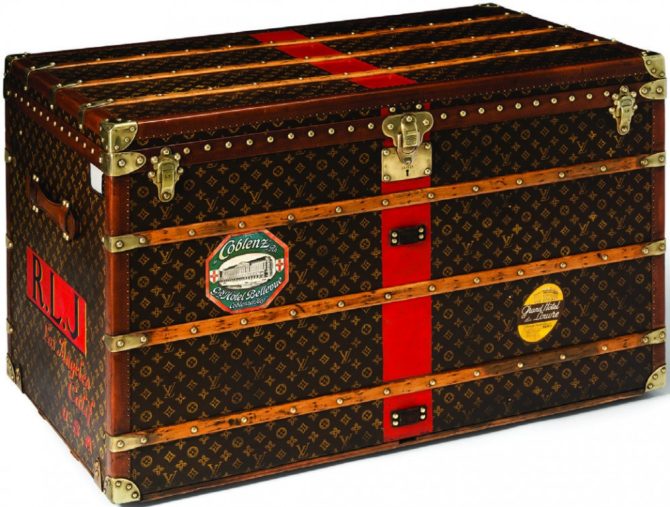

Louis Vuitton. Credit © archives Vuitton

It was understood that the elegant Parisienne was not to be seen in the same outfit for the same function twice. For a bourgeois lady of the time, whose day was a series of social engagements, this meant an average of five daily dress changes, which could escalate to eight or nine – from a relatively modest house dress to the most elaborate ball gown. With fashion’s ever-widening hoops and crinolines, a voluminous gown might comprise up to 20 yards of cloth. More dress than woman, it’s a wonder she could walk in it, let alone travel. But travel she did. And the intricate task of packing a lady’s copious attire to merge fresh and uncreased required a level of expertise beyond the skills of a lady’s maid. In 1850s Paris there were some 200 professional emballeurs; custom packers whose job it was to design, build and pack the crates and boxes that would hold a traveller’s wardrobe so, once arrived, she could carry on the daily business of lounging, visiting, strolling, entertaining, and being entertained just as she would at home.

Among the early receipts from the archives of the Louis Vuitton company – which began life as a custom packer – it was recorded that two ball gowns, suspended by a complex web of pins and ribbons, took three hours to pack. An entire lady’s wardrobe, including hats and accessories, could take days.

SPOTTING THE TRENDS

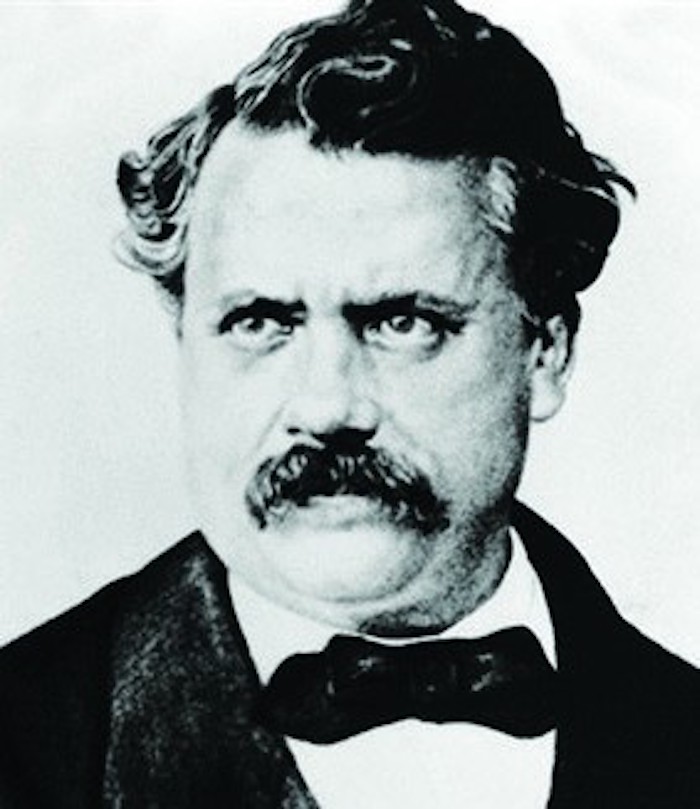

Striking out on his own in 1854, the young Louis Vuitton’s particular genius – a quality exalted by the company to this day – was his knack for anticipating the trends and innovating accordingly. From the start, Vuitton positioned his business, both physically and strategically, to be indispensable to the burgeoning fashion industry. In 1858, pioneering couturier Charles Frederick Worth, who counted among his clientele the Empress Eugénie, along with most of the Paris beau monde, opened his dressmaking atelier right around the corner and became one of Vuitton’s early collaborators. Advertisements from the era emphasise that the transport of mode (fashion) was a house speciality.

From packer to malletier (trunk maker) was therefore a short and natural step. When train travel revolutionised commerce and spawned the modern, mobile elite, Vuitton was ready. Resilient, waterproof and so lightweight they could be easily stacked for transport, his trunks helped set the standard of the day. In a span of five years, Louis Vuitton, Goyard and Moynat malletiers had all opened shops within a four-block radius near the elegant Place Vendôme. Although each approached the trade from a slightly different angle, all were rigorously committed to innovation and uncompromising craftsmanship.

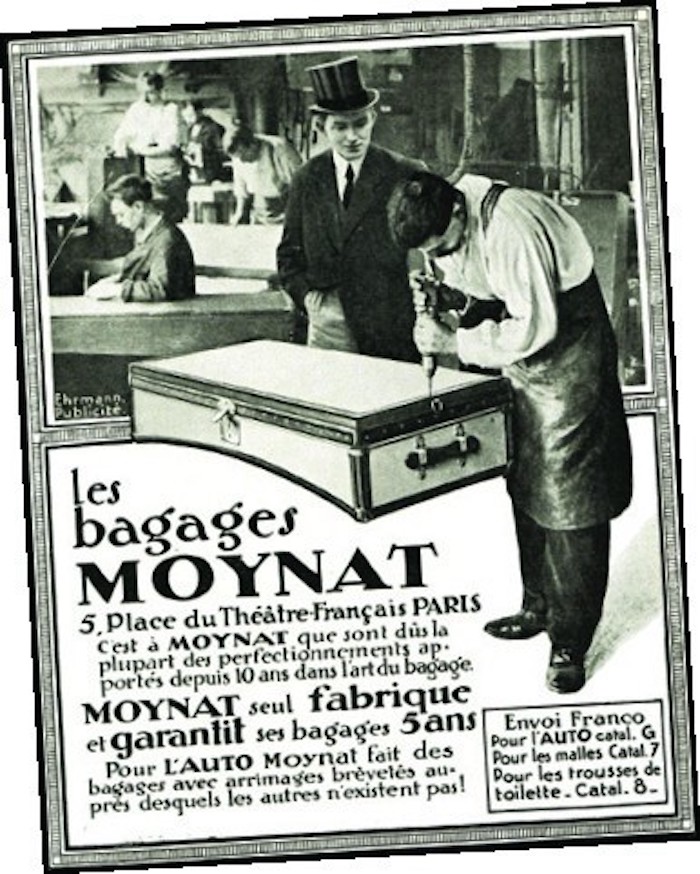

Pauline Moynat was the last to Paris, arriving from the Savoie in the 1840s, but the first of the three to dedicate her shop solely to travel goods, including specialised trunks. By 1869 she was at the helm of a humming business at number 1, Avenue de l’Opéra, across from the Comédie Française and just down the street from the new Grand Hôtel. A brilliant stroke, it turns out, as the Haussmann-built avenue attracted an international crowd of tourists and soon spawned the first travel agencies.

Moynat was an innovator from the start. One of her earliest and most opportune adaptations was the use of gutta-percha, an early latex, in waterproofing her trunks – a persistent challenge to trunk makers, who used thick oil- or wax- impregnated canvas to repel moisture. Moynat also introduced ladies’ handbags in her travel business. Normally the purview of specialised leather goods shops not associated with travel, the Moynat bags would prove a prophetic move in the evolution from mass to individualised travel – with the coming of the first automobiles – at the turn of the twentieth century.

The Paris Exposition Universelle of 1867 was a turning point for Vuitton and Moynat and a defining moment for the trade itself. Drawing between 11 and 15 million visitors, not only did the fair introduce the art of the malletier to a vast international crowd, it gave them an unprecedented opportunity to advertise newly patented innovations, which included ingenious security devices and, for Vuitton, the first distinguishing stripes on the outside of his trunks. Malletiers also had the right to display the image of any medals won in their advertising, and the medals stacked up quickly.

The fairs ushered in several monumental changes in how the trunks were perceived, not only underscoring the trunk makers’ critical need to distinguish themselves from competitors, but also to appeal to an ever more discerning public. Function, quality and craftsmanship, particularly lightness and manoeuvrability, were always of primary concern. Now beauty and elegance were equally essential. They also had to protect themselves from imitators. To that end, Vuitton patented his Damier pattern, a chequered toile still in use today, in 1888, and, in 1896, Vuitton’s son, who had succeeded his father in 1892, patented the now iconic quatrefoils and flower pattern interspersed with the company’s LV monogram.

Around the turn of the century, the house of Goyard was consistently distinguishing itself in international fairs. The Goyard trunks and cases, made of ‘Goyardine’, a sturdy combination of hemp, linen and cotton still in use today, were covered in the distinctive three-colour interlocking chevron pattern that still distinguishes the bags – beloved of the fashion élite – to this day.

THE GIFT OF GOYARD

Though the Maison Morel box-makers and packers was founded in 1792, and had operated under the Goyard name since 1852, the more reticent and aristocratic company only began to truly hit its stride at the turn of the century, thanks in part to recognition and honours received at the world’s fairs. Goyard was a hit at the Paris Expo of 1900, where the company was singled out for the variety and elegance of its cases, and continued to distinguish itself thereafter almost on a yearly basis.

It took the advent of the automobile to usher all three houses into modernity. Innovations came fast and furiously and the visibility brought about by new outlets in France and abroad, advertising and the world’s fairs – including those devoted to automobiles and the decorative arts – catapulted the trunk makers if not into the mainstream, then certainly into a category of bespoke, luxury travel goods, that now counted smaller, more practical items among their offerings. Paradoxically, as the production of quality mass-produced luggage and small leather goods accelerated, so did the demand for an exclusivity matched only by companies with a heritage of expertise, superlative craftsmanship and uncompromising quality behind them. From royalty to movie stars, each of these companies has a glamorous cast of loyal clients that have dignified the bags from the turn of the century.

Credit © Vuitton

FASHION FORWARD

The rest is history. At the very vanguard of fashion, Louis Vuitton is arguably the single most sought-after status bag on the market. Goyard, still located at the premises it has continuously inhabited since 1834, may have been overshadowed by the explosion of the mass produced luggage and handbags from the 1970s on, but has regained its stature in the 21st century, after being purchased by Jean-Michel Signoles in 1998. Still producing the iconic totes and handbags designed earlier in the century, newer models – along with a hugely popular collection of pet accessories – can be seen on the arms of the most stylish Parisians.

Purchased by Bernard Arnault in 2010 after a 30-year hiatus, Moynat has a dazzling boutique across the street at 348 rue Saint-Honoré. Examples of historic trunks adorn the store, including the superb red Morocco trunk that won the Diplôme d’Honneur at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels. Newer models, all cleverly incorporating details from the classic designs, mark some of the most beautiful and distinguished totes, bags and small leather goods in Paris today, not to mention the exceptional bicycle picnic trunk and handmade bespoke luggage that cost well into the five figures. Under the artistic direction of Marc Jacobs since 1997, Louis Vuitton’s collaborations with artists Stephen Sprouse, Takashi Murakami and Yayoi Kusama, as well as many high-concept collaborations with fine artists, like James Turrell and director Robert Wilson, run from the flamboyantly subversive to the sublime.

The story continues: a story of passionate devotion, innovation, craftsmanship, exclusivity, luxury, prestige and endurance, but most of all, a story of Paris.

From the France Today archives

Credit © Vuitton

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *