Life is a Cabaret: Discover the World of Parisian Cabaret

Welcome to the world of Parisian cabaret. From political satire to feminist empowerment, Chloe Govan explains why this centuries-old art form, as sparklingly sexy as it may be, is very much ahead of the curve

Backstage, clad in her red velvet Moulin Rouge-branded dressing gown and signature Swarovski earrings, the elegant principal dancer before my eyes is known simply as Claudine. Yet once she hits the stage, she transforms into the evil monster Medusa, donning a headdress depicting venomous snakes and beckoning vulnerable co-dancer Olga into an underwater aquarium crammed full of 60kg pythons. Other guises include a Siamese twin at the circus, a cartwheeling gymnast and a feather-clad showgirl.

Moulin Rouge principal dancer Claudine with her silvery Medusa headdress. Photo: Chloe Govan

With 60 classically-trained dancers, 1,000 costumes, a circus, an underwater snake pit, ventriloquists, comedians and even six miniature ponies, the Moulin Rouge is one of the most lavish cabarets in the world; and it delivers nothing less than extreme, high octane glamour. Its current show Féerie boasts an €8 million production budget, and features hundreds of painstakingly stitched costumes, each of which took up to 280 hours to create.

Yet, in spite of such impressive credentials, this world-famous venue is about much more than merely bejewelled bras. As the gently undulating sails of the iconic red windmill fade momentarily from our minds’ eyes, let’s travel back in time to an era before the Moulin Rouge existed to discover how it began. Back in the early 1800s, Montmartre was not yet part of a bustling capital city, but rather a rural village surrounded by vineyards and windmills and populated by nuns. In the years to come, the nunnery would be replaced by debauched drinking dens, but not before the war of 1814, when the Russian Cossacks stormed Montmartre and ravaged its thriving agricultural scene.

The Moulin Rouge. Photo credit: Moulin Rouge/ D. Duguet

In the bloodthirsty fights that ensued, one of the founding brothers of Montmartre’s windmill industry was crucified on the sails of his own mill. A surviving sibling installed a red windmill on his grave as a tribute to the bloodshed suffered; and that gesture inspired the first incarnation of the Moulin Rouge.

The windmills had regularly been used to crush grapes so the obvious choice in the aftermath of the war was to turn them into drinking dens where locals could drown their sorrows by imbibing in wine. They became safe havens to drink, dance and be decadent. These venues were frequented – and painted by – the likes of Van Gogh, Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec. Their presence spelt the beginning of the creative and artistic atmosphere for which Montmartre is still admired today.

Many cabarets sprung up in the district, yet by the end of World War II, only Picasso’s favourite venue, Au Lapin Agile, and the Moulin Rouge – immortalised in Lautrec’s paintings – had survived the test of time. The garden of the latter even boasted a huge elephant. Guests entered via a spiral staircase in its leg, and watched belly dancers gyrate within.

The windmill-topped venue also gave birth to the dance now known the world over as cancan. Its showgirls graced the neighbouring vineyards for the annual wine harvest festivities and were photographed seductively feeding each other grapes while dressed in their most bouffant skirts. The pinup posters sold as a result allegedly raised money for the region’s orphans and war casualties.

Performers swing from a giant chandelier at the Lido. Photo: Gregory Mairet/ Lido

DEFIANT SHOWGIRLS

The Moulin’s most famous dancer was Mistinguett, who reportedly insured her legs for 500,000 francs – nearly half a million times more than the cost of an entrance ticket to the show. She counted Oscar Wilde and Jean Cocteau among her closest friends. Another favourite was La Goulue (The Glutton). Living up to her stage name, she would earn her tips by snatching patrons’ glasses as she shimmied past and downing the contents in a single gulp.

In a world of anorexia and restrained eating, the image of a feminist dancer glugging her guests’ absinthe while remaining defiantly unconcerned about her figure is a powerful statement indeed.

Cut to 2018 and the show is still a celebration of women – not least because guests crack open 240,000 bottles of Champagne there every year. Yet Montmartre’s wartime angst will never be forgotten. Its historical context lends an alternative meaning to modern scenes such as the snake pit act. With a little imagination, we can almost see Olga representing a Cossack rival, and Claudine luring her into the snakes’ underwater den as vengeance for the attack on her country. In the past, disparaging reviews have dismissed the Moulin Rouge as a mere “Disneyland with breasts”. Yet how many competitors have featured underwater dancing in a pit of snakes, or an ice-skating damsel being swung in circles above her equally acrobatic partner’s head? Not to mention the ventriloquists, comedians and gymnasts who entertain between each act? To dismiss the show as striptease would surely be an injustice to all of its classically trained dancers, for whom an eight-minute act packed with high kicks and cartwheels takes a month of intense practice to master.

It’s showtime for this Lido dance. Photo: Gregory Mairet/ Lido

While cabarets are often accused of sexism and objectification for portraying women topless, perhaps it is more sexist to presume that overtly sensual women cannot simultaneously be talented and creative. That is the opinion of Victoria, a Bluebell Girl at the Lido, although she believes native Parisians are less prejudiced and rarely see topless revues as scandalous.

“Cabaret is absolutely a feminist statement,” she elaborates. “[Going topless] is very much accepted here and it makes us feel powerful. While it would be received very differently in England, it’s a tradition in Paris to show a bit more skin.”

A prime example is a Lido act that brings a whole new meaning to the term “swinging from the chandeliers”. A Swarovski fetishist’s dream, it features scantily clad dancers writhing on a giant, glittering chandelier.

The Paradis Latin. Photo: Angelo/ Paradis Latin

LATIN PARADISE

Meanwhile, across town in the heart of the Latin Quarter lies another cabaret treasure: the Paradis Latin. Originally commissioned by Napoleon and built by Gustave Eiffel, the creator of the Eiffel Tower, it invited intellectuals and libertines alike to cabaret extravaganzas. Ultimately it became a war casualty, damaged by fire. Yet, when it was renovated, secret historical relics began to reveal themselves, such as a hand-painted cupola and posters of glamorous dancers, hidden among the rubble. A property developer resolved to bring the original cabaret back to life and 45 years later, it is still a roaring success.

Its secret is authenticity. The venue has remained small and intimate, with coach-loads of package tour pleasure-seekers notably absent. In fact, the majority of visitors are locals. Onlookers are often close enough to the stage to see the high-definition suppleness of the dancers’ legs as they perform high kicks; their limbs are lithe, doll-like and seemingly lacking a single imperfection. Guests are invited to feast their eyes on a Venetian masked ball, a Château de Versailles-style gathering in drag and a Romeo and Juliet wedding scene, with the leading lady sporting just a pair of crystal-studded panties and a sheer wedding veil.

The Paradis Latin also celebrates men. They obligingly perform press-ups, simulate massages on each other and ex their muscles while topless. On occasion, ambiguity exists as to whether their exaggerated sexuality is a parodic act or a genuine part of the show. Yet those arguing that women are objectified will be met with gender equality here, as men are presented in exactly the same way.

Then, there is the unicyclist bartender perilously juggling Champagne bottles while balancing implausibly tall towers of plates on his head. Yet, perhaps the biggest draw remains the traditional cancan. “No matter what,” principal dancer Vanina assures me, “every show is all about the cancan!”

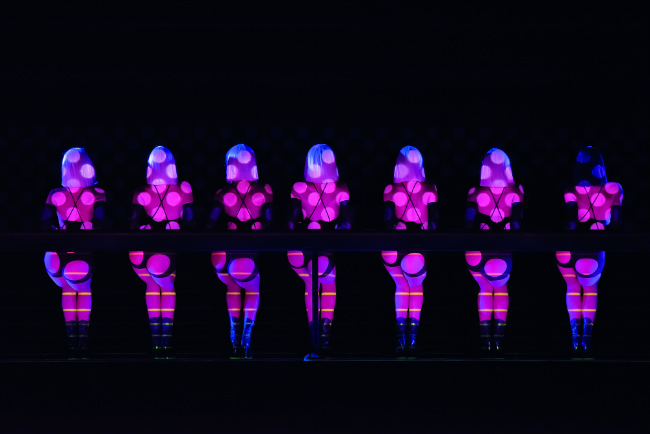

The Crazy Horse uses a body scanner to map light projections to each dancer’s specific measurements and proportions. Photo: Vlada Krassilnikova @GEvolution

The Crazy Horse, on the other hand, has reinvented cabaret, creating a modern version of the art form as far away from its traditional roots as an observer can imagine. It portrays a world of intoxicating surrealism where laser lights are projected onto performers’ bodies to cloak them in leopard print and polka dots. The show pioneers modern technology, using a body scanner to map light projections to each dancer’s specific measurements and proportions – a technique first tested out on Dita Von Teese.

The company is equally modern in its attitude to the female body. While Moulin Rouge strictly controls dancers’ weight to ensure they maintain an impeccably lithe figure (they are forbidden, for example, to gain or lose more than two kilos), the Crazy Horse champions diversity by including curvaceous performers such as Lolly Wish. Like La Goulue before her, Lolly – who sings between acts with performance partner George Bangable – is unapologetically voluptuous, and a strong advocate for body positivity.

The Crazy Horse welcomes a natural, womanly aesthetic, to the point that it has banned plastic surgery and tattoos, while collaborations with celebrities such as the buxom Beyoncé demonstrate the company’s commitment to curves.

Yet, perhaps the most subversive entertainment of all is at La Nouvelle Seine. In the days of Dumas, long before it became renowned for sparkles and sex appeal, cabaret was used as a means of delivering political satire and caustic, biting humour, and this burlesque club on a boat brings us back to those traditional roots.

POLITICAL SATIRE

At first glance, the boat is indistinguishable from any other pleasure cruiser docked on the river Seine, and most would walk past none the wiser. Yet to step inside is to discover a secret world where savagely satirising politicians in the name of self-expression is a de rigueur art form.

One act makes a mockery of the United States’ consumption culture and obesity crisis, depicting a woman wrestling with a giant inflatable hamburger to the tune of Lenny Kravitz’s American Woman. Other performers don neon-orange face masks in mockery of Donald Trump.

Meanwhile, French political figures are on the hit- list too – most notably President Macron. The showgirls jeer at superficial members of society who they believe vote for the politician they deem the most sexually attractive instead of the one most suited to the position.

Political satire and caustic, biting routines are La Nouvelle Seine’s bread and butter. Photo: Didier Bonin

Besides light-heartedly belittling their own president, other themes have included body positivity, arguing via the medium of dance that a woman should be considered sexy regardless of her size.

In chic Paris, where a fashion model figure is often regarded as an expectation in the performance world, the celebration of voluptuous women is positively revolutionary. Thus while big-budget cabarets ooze professional glamour at its best, it’s the clandestine backstreet clubs and boat parties where the political revolution takes place. There, creatives step out of the shadows to deliver an uncensored and authentic view of real life in Paris.

Regardless of your preference, the City of Light offers entertainment for everyone.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *