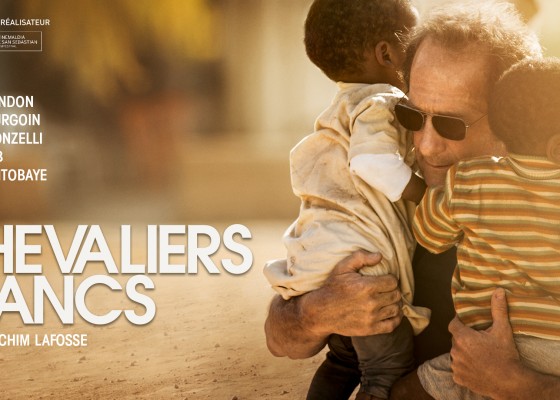

French Film Reviews: Les Chevaliers Blancs– White Knights, Black Pawns

Les Chevaliers Blancs (The White Knights), a new film directed by Joachim Lafosse that is making waves in France, is based on an NGO scandal of a few years back. The people running an organization called L’Arche de Zoe (literally Zoe’s Ark) got involved in shady adoptions and wound up behind bars. The film inspired by it (here the group is called Move For Kids) is unsettling and insightful in its way, and definitely worth seeing, but flawed. Like certain other directors, Lafosse mistakes opacity for ambiguity. It’s one thing not to give us pat answers, another not to give us a clear-enough frame to pose intelligent questions.

The story takes place in the desert hinterlands of Chad. The local government is corrupt, rebels control the countryside, Western peacekeepers are heavy-handed and thuggish. Like besieged settlers in the Old West, the NGO volunteers, doctors, and one journalist, are barricaded in an encampment. The leader of the volunteers is Jacques Arnault, played by Vincent Lindon. He seems like a tough-minded professional with, down deep, a good heart. He’s a specialist in getting things done, and isn’t above telling a white lie or two. His group’s project is ostensibly to establish an orphanage to house, school, take care of young parentless children.

The director is so good at portraying the physical landscape that we’re ready to believe whatever we see in this forbidding, unlikely setting. He vividly brings out the dust, the heat, the enormous expanses of dry land, the brilliant blue skies. He has just as sure a hand with the human societies embedded there. The village is a tiny microcosm of struggling families, shy children, protective women, and suspicious men. At the top is the village chieftain, his traditional clothes offset by jacket and wire-rimmed glasses. He is Arnault’s counterpart, a man ready to lie and finagle in the interests of the village people (especially himself).

The other society is that of the expatriated volunteers. The film depicts the alienation that turns into fractiousness, as members of the group get cabin fever from being penned up in their base, and are gnawed by doubts about their mission. Some of them see their situation as a sort of Club Med (more out of desperation than cynicism), and get rebuked by others who are more serious-minded (and maybe sanctimonious). The director gets a little heavy-handed here. It’s odd that there are no amatory entanglements between the volunteers or between the volunteers and the locals. Yet in a way this underlines the sense of uprooted alienation.

On one hand, Arnault’s character holds things together, but that will also result in the others being overly dependant on him. This also holds true on the filmic level. Lindon gives a strong, dominating performance. The other actors seem to fade into the background before his presence, and it takes a while for their characters to make themselves felt. Louise Bourgoin embodies fine mettle in her performance as Laura, who seems to be the group’s second in command. Valérie Donzelli, as the resident journalist, is also good, in a more ambiguous way, someone involved in the goings-on but remaining on the outside, who maintains the integrity of her journalistic mission in a way that is a bit too self-contained. Reda Kateb as Xavier, a sort of go-between, is very good dramatically, but his character remains vague.

Gradually a web of deceit is woven from both sides. The village’s parents (at least the mothers) want to give up their offspring to the new orphanage, going so far as to pretend the children are orphans. Arnault and his colleagues demand very young children exclusively. Eventually we understand there is an adoption angle. Or is it foster care? Or the long-distance sponsorship that numerous charities practice using the word “adopt”? This seems like a fascinating can of narrative (and moral) worms.

Certain plot beats fall into place. The obsession with young children, the interest in planes and landing strips, the readiness to disburse cash. But the director doesn’t give us enough of the shifty and/or confused thoughts, feelings and motivations of Arnault, or the other characters. Those of us who remember the real case will be able to fill in some of the gaps. But for others there are too many blanks. The abrupt ending, which closes the curtain on the whole affair, doesn’t really help. The director reportedly said he didn’t want to be “judgmental” about the characters. It’s true you can’t be judgemental about a blank. But you can’t be insightful about one, either.

Production: Versus Production/Les Films de Worso/France 3 Cinéma/Le Pacte/Proximus

Distribution: Le Pacte/O’Brother Distribution

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *