Chanel’s Métiers d’Art

As haute couture recedes as even a remote possibility for the vast majority of women, the interest it inspires has never been greater. Witness the blockbuster crowds in New York that mobbed the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, in 2011, and now Charles James: Beyond Fashion. In Paris, the Musée Galliera’s Paris Haute Couture at City Hall, in spring 2013, and the superb Alaïa, the Galliera’s inaugural exhibition for its reopening in late 2013, also drew rapturous crowds.

It’s no coincidence that major museums are investing millions to rejuvenate their costume departments: whatever your stance on its relevance to fashion, to culture, to life, haute couture is undeniably an art form.

The couturiers that stand out in the history of fashion determined much more than the length of a hem or the turn of a sleeve. Like any creative virtuoso, a great couturier transforms perception itself, pushing against social mores in ways both subtle and outrageous (sometimes both) to usher in an original idea of the new.

Saving the Ateliers

Yet even as couture deftly manipulates the codes of attire, it does so within a set of rules as invisible as a splendid garment is visible. And it is never done alone, but relies on anywhere from an elite assembly to a small army of skilled craftspeople labouring uncompromisingly on a single garment. As Olivier Saillard, director of the Musée Galliera and curator of Paris Haute Couture, points out in an essay included in the exhibition catalogue: “Its components – the precious materials used and the meticulous attention to detail of the artisans who help to produce it – sometimes eclipse the finished work, which is both a unique creation and a collective effort.”

The exclusive creations that show up on red carpets and fuel blockbuster exhibitions rely as much on a singular vision as they do on the craftspeople behind them. This is something Chanel understands very well.

In the Paris suburb of Pantin, a complex of bright new ateliers house some of Paris’s oldest and most venerable master craftspeople called métiers d’art, or masters of art, who hand-craft the buttons and embroideries, feathers and flowers, jewellery, gloves and headwear integral to Chanel’s and other fashion houses’ fine couture collections. Since 1977, Chanel has been slowly and discreetly acquiring Paris’s small, traditional companies – many of whom worked directly with Coco Chanel herself – not as an act of charity, or even of prescience, but of self-interest and survival.

In the 1920s, when Gabrielle Chanel was establishing her Rue Cambon empire, there were hundreds of ateliers that supplied Paris’s haute couture industry. That is, exceptional hand-sewn, made-to-measure clothing from distinctive maisons that catered specifically to individual buyers, as distinguished from ‘petite’ and ‘moyenne’ (average) couture, made by tailors and dressmakers who accommodated a middle- and working-class clientele.

Couture translated literally from the French means “dressmaking”. These highly skilled men and women produced everything from the exquisitely detailed beading or embroideries on a gown to the finely articulated feathers sewn onto a cape or hat.

Nowadays, a huge majority of those ateliers are gone. The handful that remain are the guardians of the rarified skills and techniques that are the essence of haute couture. Chanel’s initiative, which falls under an independent subsidiary called Paraffection (“with affection”), seeks to preserve these companies, some well over a century old, that have passed down their expertise from generation to generation. These encompass Lesage the embroiderers, the feather specialists Lemarié, hat-maker Maison Michel, the button and notions manufacturer Desrues, Goossens the goldsmiths, glove-makers Causse, the exclusive custom shoemaker Massaro and many more.

As these small ateliers found themselves without a successor, or were ready to sell, Chanel was there, understanding that the loss of skilled artisans – les petites mains – and even their traditional tools, meant the loss of an irreplaceable know-how. For Chanel, and every other luxury house, many of whom commission the same ateliers for their collections – including Louis Vuitton, Dior, Givenchy and Valentino – the economic impact of that loss would be huge.

During a visit to the Pantin ateliers in February, Karl Lagerfeld, Artistic Director and head designer at Chanel, and Aurélie Filippetti, the French Minister of Culture emphasised another crucial aspect of the project, the historic archives; an indispensable resource for present-day couturiers and their apprentices.

Of all the maisons employed here, the embroidery house Lesage is among the best known in France. In business for 90 years, they can in fact date their origins more than half a century earlier, to the very birth of haute couture.

“The archives of the Maison Lesage are housed here,” says Filippetti. “In reality, the oldest samples, dating back to 1858, are those of Michonnet, embroiderers under Napoleon III for the Empress Eugénie. Englishman Charles Frederick Worth, the father of couture, ordered his first embroideries there. In 1924, Albert Lesage bought these ateliers and later collaborated with Vionnet, Schiaparelli, Balenciaga.”

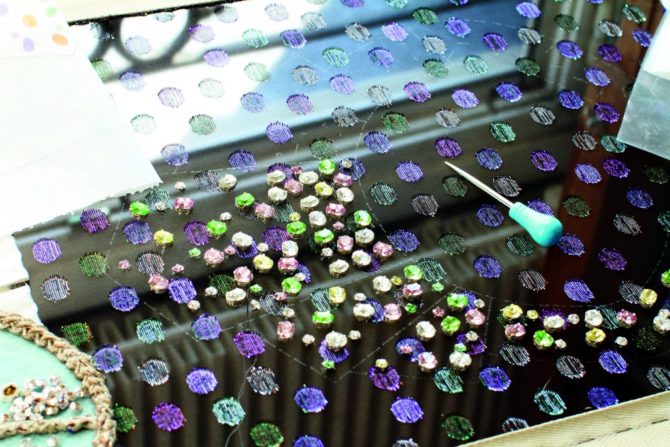

The Lesage archives are a treasure trove. More than 60,000 samples, representing thousands of motifs dating back 150 years, illustrate the history of fashion from its origins to the heyday of couture in the 1920s and 1930s– everything from the most delicate florals and vine patterns to the more avant-garde designs created with Elsa Schiaparelli, Balenciaga and Dior. Ironically, Coco Chanel was one of the few great couturiers of the day that didn’t patronize Lesage. She refused to do business with any supplier who worked with her arch-rival, Schiaparelli.

Paraffection’s Houses

Many other ateliers now under the Paraffection umbrella also made lasting contributions to the Chanel myth. Custom shoemaker Maison Massaro, who teamed up with Coco Chanel to develop her signature black-toed ivory sling back, traces its history to 1894, and has counted the Duchess of Windsor, Marlene Dietrich, American heiress and fashion icon Barbara Hutton, and King Hassan II of Morocco among its clients. Massaro’s exclusive Rue de la Paix showroom still caters to a privileged private clientele (at €3,250 a pair, walk-ins to the plush showroom are rare), and is a favourite of couturiers Karl Lagerfeld, Azzedine Alaïa, Christian Lacroix and Thierry Mugler, among many others.

Chanel met Robert Goossens in 1953 and immediately recognized a kindred spirit. A brilliant craftsman, he was also adventurous, well versed in the lore of jewellery and able to transform base metals, crystal, faux pearls and semi-precious stones into extraordinary jewels.

Together, he and Chanel created the house’s most enduring pieces: the long gilded-bronze and rock crystal ‘sautoir’ necklaces that Chanel adored, cultured pearl necklaces and broaches and Byzantine-style cuffs. This fruitful collaboration marked the very birth of ‘vrai-faux’ jewellery – unabashedly ‘costume’, these hugely popular adornments stood out for their bold yet elegant designs.

Martine, the daughter of Robert, is now the chief designer for Goossens, which still adheres to the house’s traditional style. Though the house’s ateliers are in Pantin and elsewhere, the full jewellery line can be found at the Goossens boutique, at 42 avenue Georges V, with necklaces starting at around €400.

Founded in 1880, Lemarié was once just one among some 300 houses that specialised in fashioning the legions of feathers and delicate fabric flowers which adorned dresses, hats, capes, bustles, muffs and mantles. By the 1950s fewer than 50 houses remained. Today, Lemarié are nearly the last feather and flower makers for luxury couturiers. Although once popular, heron and egret feathers are a thing of the past – the company now uses ostrich, swan, emu and vulture plumes. It was Lemarié that fashioned the first of Chanel’s iconic camellia blossoms. Today, the company fills an order book with more than 20,000 meticulously hand-made flowers each year.

A more recent acquisition, Maison Causse, is France’s oldest luxury glove maker, founded in 1892 in Millau, the traditional glove-making capital. Intended to accessorise as much as protect, these high-fashion gloves are made of luxury leathers – lambskin, peccary, reptile and crocodile –and embellished with stones, fur or lace. Causse’s handsome, wood-panelled boutique on Rue Castiglione is the go-to place for stylish Parisians. One of only four remaining traditional gantiers in France, Causse is called upon to accessorise dozens of couture collections, including Chanel’s.

Showcasing Couture

As interest in every aspect of the luxury market grows, so has the spotlight on these ateliers and the rarefied skills necessary to haute couture. “Haute couture is a niche market,” says Bruno Pavlovsky, Chanel’s President of Fashion, “but it is a dynamic market.”

To highlight this aspect of couture, Chanel hosts the Métiers d’Art fashion show, a once-a-year extravaganza that is held in a different city each time. The mastermind behind the show, Karl Lagerfeld, attends, along with representatives from the ateliers, who demonstrate what makes the clothes so special.

The Métiers d’Art collection isn’t technically haute couture, since the clothes aren’t made-to-measure, nor is it ready-to-wear, but a hybrid of the two. Though still steep, the collection’s prices are gentler than haute couture, with a two-piece ensemble costing somewhere around €22,000, shoes approximately €800 and a bag in the neighbourhood of €7,350.

“Haute couture is for everyone”, says Pavlovsky. While this may sound absurd, apply to it the rationale of a Matisse painting or a beautiful sculpture preserved in the Louvre. For some of us, couture may be pure voyeurism, for others, the stuff of dreams. More than throwing a life jacket to a dying old-world art, Chanel has once again proven its foresight, by preserving something essential to what the company stands for along with a cultural legacy.

Saving these ateliers may make the best economic sense, but bound up in Chanel’s pragmatism is a reason as poetic and ephemeral as beauty itself.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *