Belle Epoque Photography: A Very Modern Art

What happened when 19th-century artists took their first peek through a camera lens.

They were amongst the greatest painters of the 19th century, but when it came to the thoroughly modern art form of photography, the likes of Edgar Degas, Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard had to go back to the drawing board. Initially, artists scorned the new invention: threatened by photography’s portrayal of reality, some suggested the genre was too superficial. Painter and sculptor Honoré Daumier said, “photography imitates everything and expresses nothing”, while essayist Charles Baudelaire dismissed the medium as “the refuge for bad artists”.

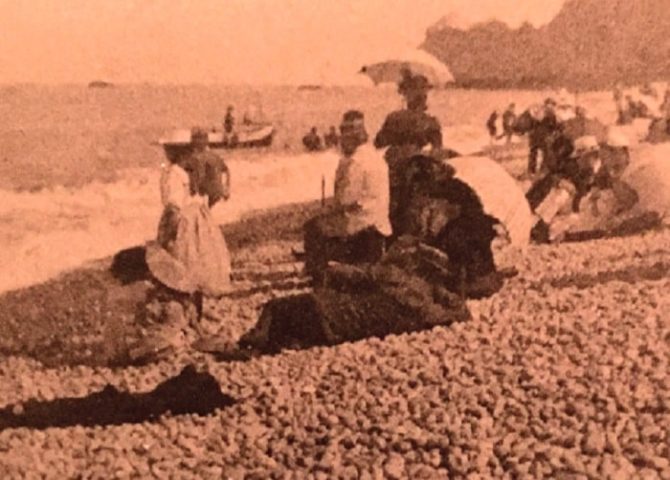

Felix Vallotton’s painting of the 1899 photograph of the beach at Etretat

Nevertheless, scorn for the camera didn’t stop some artists from dabbling in photography. Painters adopted photography as a tool to record a streetscape or a model’s pose. Its spontaneity suited the Impressionists’ newfound interest in modern life: some translated their photographic results directly onto their canvases where parallels between the two media were easily seen; other French artists took photos for their own enjoyment. Selfies, it seems, are nothing new.

Degas’ picture of a woman drying herself after a bath. Public domain

For Degas, photography was a new way of seeing. Afflicted by lifelong eye problems, the camera helped him to focus. He became passionate about photography when his time with the Impressionists ended and went on to become a capable photographer who developed his own prints. It was the theatricality of photography which he enjoyed: his well-composed photos were darkly mysterious. Due to his penchant for voyeuristic perspectives, Degas’ camera caught awkward ‘keyhole’ moments: found amongst his possessions was a photograph inspiring the contorted pose of a ‘Woman Drying Herself’.

Only 50 of Degas’ photographs survive today. One of his most famous is a double portrait of Pierre-Auguste Renoir and the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, in which the duo lean against a mirror in which is reflected the flash of Degas’ camera.

Degas’ painting of a woman drying herself after a bath. Public domain

Édouard Vuillard followed Degas’ example as a painter-photographer. Best known for his colourful, intimate interiors, Vuillard belonged to a small group of painters known as Les Nabis. He started taking photographs around 1895, capturing nearly 2,000 snaps of his family and close friends. The invention of the Kodak handheld camera in 1888 invigorated the methods and creative vision of many late 19th-century artists. “Un instant, s’il vous plaît.” Using a handheld Kodak, Vuillard clicked his accordion-pleated box camera at his frozen subjects and produced surprising, inventive results. He was obsessed with Misia Natanson, a patron of the arts and artists’ model whose husband was the publisher of La Revue Blanche. If you look carefully you will see that she was the true focus for many of Vuillard’s group photographs.

One of Édouard Vuillard’s many shots of Misia Natanson. © MOMA New York

BEHIND THE LENS

Travelling within the same artistic sphere were Pierre Bonnard and Félix Vallotton, both of whom were captivated by the Kodak. For Bonnard, known for his paintings with large planes of bright pink and yellow-gold, the 2D quality of the medium echoed the aesthetic flatness favoured by Les Nabis. This vision was more important to Bonnard than expertise and thus his photos, like his paintings, feature mysterious silhouettes and vague outlines. Bonnard printed around 200 photographs during his lifetime.

Pierre Bonnard’s selfie. © Harvard Fogg Museum

Meanwhile, Félix Vallotton produced just 20 images and destroyed them due to outside criticism. Many painters’ photographs weren’t publicly displayed: for instance, the heirs of Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau hid his photographs in order to preserve his reputation. Their paintings were beautiful and virtuous, but their photography showed the truth, leading Belle-Époque painters to reassess what it meant to be an artist.

From France Today Magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in art, Art history, French art, photography

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY