“La Mode Retrouvée” at the Palais Galliera Showcases Paris’s First Fashionista

In today’s throwaway fashion culture where Zara and Macy’s outfits cost as much as a nice lunch and hardly last a season, it’s inspiring to see the Belle Époque clothes of la Comtesse Elizabeth Greffulhe at the Palais Galliera in Paris. But the real story of this fashion and society superstar is that behind the beautifully designed wardrobe was an intelligent, creative woman who influenced artists, writers, politicians and scientists.

Let’s start with the clothes in the “La Mode Retrouvée” (Fashion Regained) exhibit. They are detailed, timeless creations by the top designers of the time – Worth, Lanvin, Fortuny, Nina Ricci and more. The elegant designs use colors of green, pink, black and white, and floral. Seams are cut at 90 degree angles; collars are layers of embroidered flaps lying like petals or bat wings; velvet, silk, taffeta and chiffon fabrics are rich and reflect patterns of the orient or the garden; and trims are embroidery, beads, fur, mirrors and even gemstones.

Add the woman, and it gets really interesting. Elizabeth was born in 1860 into a prestigious Belgium family that was treated almost like royalty, but they were penniless. She was taught literature and music, a rarity in those days, which would be a basis of strength in her life. At 18, she married Viscount Henry Greffulhe whose family had a fortune in banking. Elizabeth met Henry only twice before the marriage. After the honeymoon, she was stationed in the family’s gloomy chateau 125 miles south east of Paris while Henry returned to his preferred life of mistresses and hunting.

Countess Greffulhe was expected to produce a male heir, but instead gave birth to daughter Elaine. When Elizabeth’s mother died, she lost her friend and confidante, but inner strength guided her to an outlet beyond the stifling, high society etiquette rules dictated by the Greffulhe family. Henry liked to show off his slim, beautiful wife at social events, and Elizabeth began to earn a reputation of a “pleasant and witty woman,” as she wrote. “There is only one thing to do, and that is … not to look insignificant to others and … organize my life and my amusements for myself.”

Robert de Montesquiou, Countess Greffulhe’s uncle, poet and dandy, was enlisted to help. He encouraged Elizabeth’s original fashion taste and supported her social activities. But it was Elizabeth who turned fashion and social into a “strategy for prestige,” and wrote the rules for her place in society.

Countess Greffulhe became the acknowledged leader of Paris’ social elite from the 1880s through the 1930s. Shrewdly, she used the position with flair and savvy to influence the powerful and fulfill her sincere desire to be useful. Elizabeth was an early adaptor of fundraising, and was the founding president of the Société des Grandes Auditions Musicales de France. She raised funds for producing operas and shows, including Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde and Twilight of the Gods. She supported the Ballets Russes and Isadora Duncan. Richard Strauss conducted Salomé in Paris. An international competition to support young composers was created. Music festivals in Versailles and Bagatelle were organized. She even introduced greyhound racing to France.

Countess Greffulhe was also interested in science. She arranged the financing for Marie Curie, who had struggled for years, to open the Institut du Radium, which is now the Institut Curie. Edouard Branley’s research of radiotelegraphy was supported, allowing him to develop the first device to conduct electric currents. Not only did she finance his work, but also organized public demonstrations of the technology. Marconi, who invented the long distance radiotelegraph system, used Branley’s discoveries.

Marcel Proust was an admirer. He borrowed her wardrobe, manners and style for his character the Duchess of Guermantes in In Search of Lost Time. Countess Greffulhe was the muse for many poets, musicians, photographers and artists.

The Countess did all this with the style and public relations savvy of a Kardashian. Journalists were the social media of the day and she managed them by providing highly theatrical public appearances. Controlled entrances and exits were timed to be rare and fleeting, worthy of headlines like a paparazzi photo. She chose not only the right moments, but also the right clothes.

The exhibit highlights the woman through her wardrobe. Countess Greffulhe may have used haute couture fashion designers, but she dictated the style of much of what she wore, and used fashion as a strategy. Tsar Nicholas II gave her a ceremonial cloak from Bukhara (today’s Uzbekistan) that she had Worth alter into an evening cape. The cape glowed with silver and gold disk and leaf garlands embroidered on purple velvet. Worth added rows of upright black flaps for the collar that made the Countess look like the center of a flower. She wore it twice. Once for a studio photograph, and once at a gala where Le Figaro reported she created a sensation.

Countess Greffulhe promoted black at a time when it was only socially acceptable to be worn by widows. Nina Ricci created a cream and black gown with color block panels cut in angles. The sleeves were ostrich feathers. Jeanne Lanvin designed a black satin coat with a staggered brick pattern. The bold cuffs and pockets were mink.

Tea and garden party dresses were pink or green, made of crimped silk chiffon or taffeta with orchid or lily flower motifs. The style was princess cut to show off her tiny waist, and embellished with accessories like wide brimmed hats perched on the back of the head to frame her face, tulle scarfs wrapped around her shoulders, feathered fans and silk shoes.

At her daughter Elaine’s wedding, the Countess arrived before the bride in a Worth Byzantine dress with a long train. The gold lamé taffeta was covered with sequins with a contrasting wide, mink-colored hem border. The fascinated press reported on every detail of the countess’s outfit, and barely mentioned the bride.

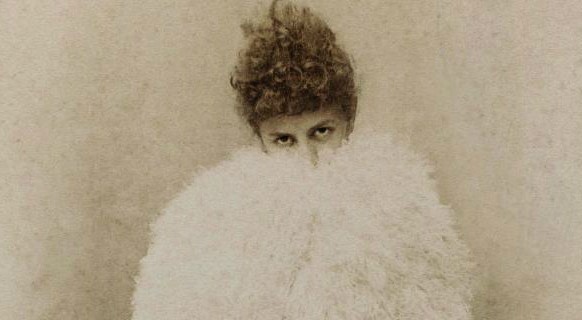

The Countess loved lilies, and she worked with Worth to create a black velvet evening gown known as “La Robe aux Lis.” Silver thread and sequin lilies were appliqued in a flowing stream in front and back. A white embroidered collar could be folded into wings or other soft arrangements to frame her face. Paul Nadar photographed Countess Greffulhe in the dress in front of a mirror, a photo that was coveted by Proust and others.

Countess Greffulhe’s wardrobe was her tool, a superpower that made the Countess stand out as a woman of persuasion. As she wrote, “Always consider the other person as someone whom you want to leave with the memory of a prestige unlike any other.”

The Countess’s prestige combined her intelligence and style to not only look powerful, but to perform powerful good deeds.

“La Mode Retrouvée” is at the Palais Galliera, 10, Avenue Pierre 1er de Serbie, 75116, Paris. It runs until March 20, 2016.

Martha Sessums is the France Today Ambassador for San Francisco.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in fashion

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *