Albertine Prize 2020: Favourite French Fiction Translated into English

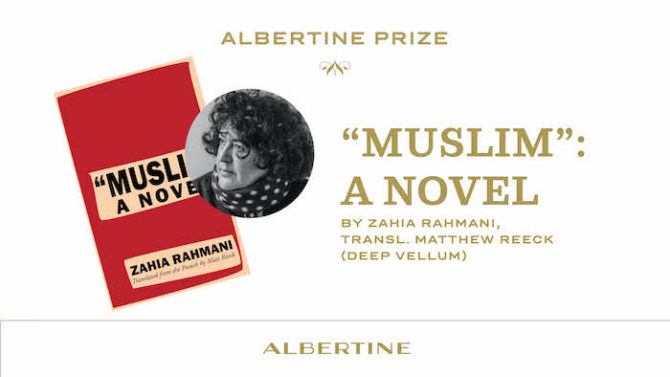

The end of the year means book awards, and the Albertine Prize 2020 was awarded to “Muslim”: A Novel by Zahia Rahmani. This novel, written in 2005, was translated into English by Matthew Reeck in 2019. It’s one thing to write a novel. It’s another thing to translate it into a different language. The Albertine Prize recognizes both jobs and awards the author and the translator.

The Albertine Prize, now in its fourth year, is awarded by the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the U.S. and is supported by Van Cleef & Arpels. A selection committee composed of a variety of U.S. and French book industry professionals pick five French novels translated into English and published the previous year. Readers are invited to vote for their favourite book, and this year’s winner was announced December 9. Albertine is the New York City bookstore that is an integral part of the Cultural Services of the French Embassy, thus the prize name. The $10,000 prize is split between the author (receiving $8,000) and the translator (who receives $2,000.)

“French books translated into English are rare in the U.S. even though French is the number one translated language in the world,” said John Freeman, Executive Editor of Literary Hub and Editor of Freeman’s, who was moderator of the online prize presentation. “Translated literature seems particularly essential and I’m pleased that despite the current complex (situation) more than 1,200 U.S. readers nationwide voted for their favourite Albertine Prize novel online.”

Photo courtesy of Albertine Books

The winning book combines fiction, poetry, lyrical essay and autobiographic elements while recounting the history of Islam as experienced by the narrator, a young Kabylian woman, who is held in a camp that feels like a prison because of her Muslim origins. She immerses herself in memories and questions her identity by reflecting on the relationship between identity and language and struggles with what it means to be Muslim. She wrestles with the languages that have defined her – Berber in Algeria where she was born and French where she went to school. She deals with violence and the denial of diversity and the novel tells her story and suffocation.

“When you travel to Senegal, to West Africa, to Bangladesh or other countries, you realize that the Muslim identity is always different,” said Rahmani. “Whereas in Europe we’re tempted to set it and freeze it into a single model. . . to put the suffering of Muslims indexed into a single cultural model. I must say that this book that was written 15 years ago did show an accentuation of problems with the Muslim world.”

The complexities of this book made it a challenge to translate, but first there’s the process for a book to even be chosen for translation and sold in the U.S.

“The first step is to sign a rights assignment contract between the French publisher and the American publisher,” said Louise Quantin, Head of the Book Department at the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the U.S. “The latter then chooses the translator with whom it wishes to work. The French publisher is not consulted and does not give an opinion. The American translator is sometimes in contact with the author and he or she can ask to exchange with the author, for example, to clarify certain points in the text or to better understand the meaning of a phrase. The author can ask to proofread the translation, but this is not always the case.”

In this case, the U.S. publisher was Deep Vellum in Dallas, Texas. Translator Reeck evidently had many conversations with the publisher before he was chosen as the translator.

Photo courtesy of Albertine Books

“It’s funny to be a translator,” said Reeck. “You think it’s going to be a direct shot to the front of the line, but then there are hurdles. . . Deep Vellum was willing to take risks and that needs to be underlined here. People can get the sense of how powerful Zahia’s book is, but also how full of risks in terms of what she is saying and what publishers will then be saying by supporting it and what readers are confronted with whether they are political ideas or difficult issues about identity politics… or what many people’s stereotypes about Muslims are.”

Reeck is also a poet and the quality of Rahmani’s writing, the way that poetry is evident in the book, was one of the attractions that made him interested in translating it. The two worked back and forth and developed a respectful relationship.

“Some authors want to be very involved with dotting every “i” and crossing every “t”, but Zahia was generous and accepting,” said Reeck. “I would ask her ‘I’m not quite sure what you mean in this passage or that passage’ and she was helpful. She didn’t say ‘I want you to say this specifically’ but it was more like ‘I was thinking of this or I was taken away by a rhythm in my language in this part,’ so it was helpful as opposed to an overly meticulous and involved author.”

On Rahmani’s end, she respects Reeck but feels the book translated in English is another book, and she’s okay with that.

“The population that is going to read this book in English has a different history than the population that is going to read this book in French,” said Rahmani. “That’s what I like so much about translation. It’s because the reception is not carried by the same reasons as in France. It’s a translation, but it’s also Matt’s language.”

Quantin agrees. “The job of a translator is particularly complex in that it involves both scrupulously respecting the original text but also playing with cultural paradigms and specificities of the language. Translators are authors, in a sense.”

“Muslim”: A Novel and the other four nominated novels are available online at Albertine Books.

Photo courtesy of Albertine Books

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Albertine

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *