We’ve Always Had Paris…and Provence

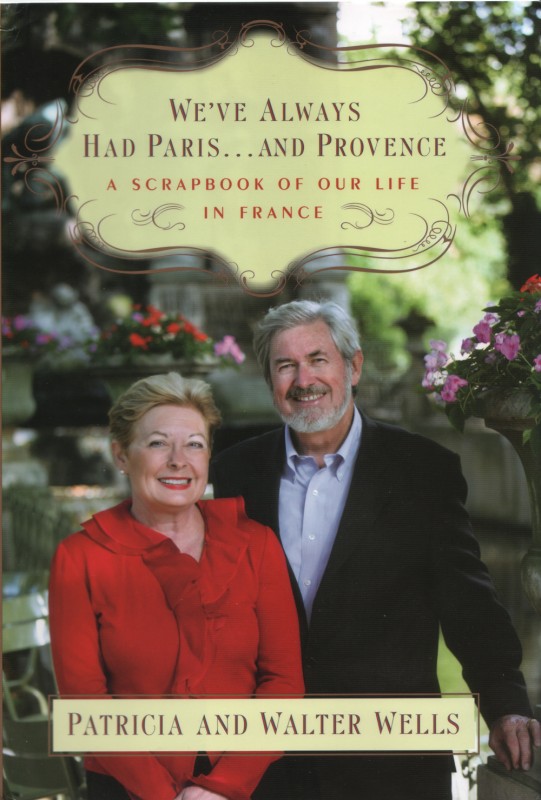

In their shared memoir, We’ve Always Had Paris…and Provence, published in 2008, Patricia and Walter Wells offer “a scrapbook of our life in France” where they have lived for the past 28 years, Walter as an editor and then editor-in-chief of the International Herald Tribune (and now France Today’s regular political columnist), Patricia as a celebrated food writer and American expert on French cuisine. In these brief excerpts from the book, Patricia recounts her long friendship with Julia Child, and Walter examines what being a Franco-American “expatriate” really means.

PATRICIA:

One of the most amazing of Julia Child’s traits was her total straightforwardness. Once, as I bemoaned a friend’s passing, she replied, in her distinctive voice, “But he had a good, long life!” No time for mourning. Move on!

Julia was a no-frills gal who thought and said exactly what was on her mind. When we cooked together, she would peel apples deftly with a knife (faster than a trio of us could peel with a vegetable peeler) and expertly open oysters, not with a fancy oyster knife but a “church key” or old-fashioned beer can opener.

I make sourdough bread regularly and for years held on to a stubborn insistence that it had to be kneaded laboriously by hand, never by machine. That was until the day that Julia-then a guest at our home in Provence-came down for breakfast and found me hand-kneading. “Get modern, Patricia!” she scolded, tossing her head side to side in bewilderment. I was forty-six at the time. She had recently turned eighty.

Julia also taught me to never stop learning, never stop asking questions, never lose that naïve curiosity or youthful enthusiasm for life. When a reader would write that he or she was having trouble with a recipe in one of her books, she wouldn’t just ignore it… No, she would go into her own kitchen, retest the recipe-and she sometimes found that, yes, it needed a bit of alteration.

Julia was human, and loved a good gossip fest. She loved to pull up a chair in front of the fire, a glass of red wine in her hand, and dish out bits of ire about those she didn’t like. But what she loved most was to cook! Whenever she visited us we seemed to have a house full of guests and she picked up an apron and a knife and went to work.

Once, lunching with half a dozen other professional women, we began playing What Would You Do If You Had All the Money in the World? Julia, along with the rest of us, agreed that she would have a hairdresser come to her house every morning, so that she could always go out perfectly coiffed. And yet she liked to say: “As long as I have a good pair of shoes and a car that works, it’s enough for me.”

Julia was never one to give false praise. Chefs always came around and wanted to know how she liked the food, hoping for praise and encouragement. Unless she felt genuine enthusiasm she would give a simple, perfectly noncommittal response: “We had a lovely time,” she would reply with a smile.

Once Julia and our friend Susy Davidson left a live Good Morning America show, had a quick lunch with the editors at Food & Wine, hopped the overnight New York-Paris flight, then immediately boarded the TGV for a three-hour train ride to Provence, a lengthy trip that would exhaust even a young and intrepid traveler. As Julia looked out the window of the train, watching the porter-less travelers struggling with their bags, she mused to Susy, “I wonder what old people do?” She was well close to eighty at the time!

In June of 1992 we were panelists at a convention in Cannes, and … as we were coming up in the elevator of the Carlton Hotel, Julia stared dubiously at my hair, which, once blond, had by then turned a mousy brown, with curly streaks of annoying gray. Julia looked me straight in the eye and said simply, “People say that women look younger when they don’t dye their hair.” Then she pronounced, in her booming voice, “Well, they are simply wrong!”

[Later that year Julia] stayed with us at Thanksgiving, on her way to close down her Provence house for good. I asked if I could buy her La Cornue stove, a shiny white Art Deco-style model she had bought in the 1960s. (For me, it would be like an analyst having Freud’s couch.) She said no. But the next morning she came down to breakfast and said she’d changed her mind. I could have the stove….

Shortly afterward, we created a summer kitchen in our Provence house, adding a stone floor, a marble sink, and Julia’s stove, a cantankerous butane gas model with an oven that seemed to have only one temperature, 450ºF, no matter how you set it.

Now, in the summer months, I have a special ritual: I strike a match to light the oven in Julia’s stove first thing each morning, then head for the vegetable garden to gather whatever is ripe that day. I prepare rustic tomato sauce and eggplant towers, stuffed squash blossoms, and roasted pumpkin, and arrange the dishes on the sturdy oven racks. I head for the gym… and by the time my workout is over, lunch has been made!

Just weeks before her death, I e-mailed Julia to thank her once more and deliver news of her trusty La Cornue. As usual, she e-mailed back within seconds, saying she only wished that she could be with us and cook once more on that stove. For years, I had saved mementos of her trips: pictures, letters, faxes, family menus… For no special reason, on the morning of August 13, 2004, I decided to frame those mementos and hang them in Julia’s kitchen. I was nostalgic and felt her presence more than ever. Then I got the call of her death. Sweet Julia did indeed live a good long life.

WALTER:

One day, turning through the newspaper looking for the latest news on expatriate taxation, it dawned on me that I had become an expat. Now, there’s frequently a typo when the word is used-it comes out “expatriot,” which must mean something like pretreasonous. That would give any loyalist a moment’s hesitation about the identity, as it did me. Yet inevitably, the term became not just acceptable but comfortable. After all, it was born of simple familiarity and not some wrenching choice between conflicting values…

…..When we moved to France it was during a brief period of détente in the long and complicated relationship between our two great republics. The French recall better than we do the importance of Lafayette and Rochambeau-and French loans and munitions-to American independence, and Americans remember the bloody sacrifice on Normandy’s beaches. Both sides oversimplify: French support for American independence had many motivations that didn’t involve the rights of man, and America alone did not put an end to Hitler’s Reich. The liberation of France eventually became a catalyst for Americans’ anger at their beholden ally, chiefly perhaps because the ally didn’t recognize just how beholden it was supposed to feel….

…..Beyond international politics, there’s all that other stuff. A French-bashing riff can go on and on-they smoke too much, lunch lasts for three hours and the rest of the time they are on vacation, they are arrogant and ungrateful-but most of the substance seems to come down to “they think they’re something special.”

Turn about: What’s the French take on us? Well, it’s equally stereotyped. Americans are children, aggressive and unrestrained… We push to the front and assume we’re in charge. We talk too loud and our clothes are sloppy… We want the antismoking laws expanded to include the sidewalks. We’re immature-ours is not the land of liberty, but of puberty. We are self-involved and self-engaged and otherwise alarmingly incurious. We threaten the climate with our greenhouse gases and pollute the world with our crass pop culture. And in business, like sports, we can be so successful because we cheat…

….Our differing insults derive from different birthrights. We really are very different peoples. The paradox is that the source of the differences is a single great parallel-we are both natively Cartesian: We are, ergo we by God are. The American variant is that we by God are the greatest. The French have certain reservations about that, because though the sun has set on empire, the Sun King’s glory still renders France unmatched for shimmer.

….Americans tend to think that their country is the greatest in the world, and with religious fervor don’t admit to any doubts about that. Whereas the French are relentless in how hard they are on France. Whatever goes awry, the French reaction will be a disgusted, “That’s France for you.” And they expect that you’ll agree. There’s plenty of criticism of America, but in my experience it’s never delivered as personal. It’s not about Americans but about policy. Bush is detested, Clint Eastwood is loved.

…..Why, when we’re so different, do we pay so much attention to what the other thinks? What’s wrong with thinking “vive la différence” as well as saying it?

I’m not sure that in our long interlude [living in France] we cracked the code to that difference, but one thing we came to understand helped persuade us to stay. In France, pleasure is okay. We Americans have famously and formally declared our right to pursue happiness….But we tend to talk about pleasure in terms of sin. The French are entitled to pleasure without guilt. In fact, except in a legal sense, my observation is that guilt is rarely discussed in France-unless you don’t follow the rules. If you follow the rules, there’s no reason to feel guilty.

Patricia and I never fled the United States, of course, nor have we ever thought of ourselves as exiles. We chose new jobs, not a new country. In the best traditions of the American frontier we were looking for adventure and opportunity. And though we learned a new language and a new code and gained perspective, neither of us ever traded in our basic values, the ones we call “American” but that we might instead simply call “humanist.”

So, back to that problematic identity: expatriate? I would rather think of myself as just someone who, like Benjamin Franklin in Paris, was accused of going native, and, like Jefferson, loves both his countries.

Originally published in the July/August 2008 issue of France Today.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email