The Murals of Lyon

In Lyon the walls tell stories, mostly very tall tales. While painting on walls is as old as time, the city has taken the art of modern urban wall painting to new heights with nearly 60 outdoor murals. Some are breathtaking flights of fancy; others are marvellous examples of trompe l’oeil, depictions of everyday life so realistic you could almost walk into them.

Lyon’s love affair with mural art is mostly due to a series of chance encounters more than three decades ago. In the early 1970s, a group of local students got to discussing the closed nature of the art world, concluding that art was a form or expression largely confined to galleries and museums. Murals, they decided, would bring art to ordinary people. They would be direct, effective in portraying ideas, and free.

A group of ten students went to study modern wall painting in Mexico, where Diego Rivera had launched a new artistic tradition in the 1920s with a series of powerful, storytelling murals that modified Renaissance techniques to convey modern political messages. CitéCréation, their student cooperative movement, was born.

In 2008 CitéCréation celebrated its 30th anniversary, with many of the original members still active. Today the collective is based in the suburb of Oullins south of Lyon, in an old school building that was donated to the city in the 1800s by François Barthélemy Arlès-Dufour, a humanist, businessman, leading member of the Saint-Simoniens ideological movement and a co-founder of the French bank Crédit Lyonnais, now known as LCL.

When they started, according to CitéCréation’s Halim Bensaïd, Lyon was a fairly dark city. “It was known only for Paul Bocuse and the traffic congestion in the Fourvière tunnel,” says Bensaïd, now an internationally acclaimed mural artist. “It was industrial, polluted and sad.” The new mayor at the time, Michel Noir, decided to brighten it up, launching various programs to clean up and rejuvenate the city’s public squares and historic buildings. His drive brought him into contact with the struggling muralists of Oullins, who found themselves in the right place at the right time. “If we had tried to get started 10 years earlier,” said Bensaïd, “it might have been a very different story.”

The murals produced by CitéCréation were designed not just as decoration but to help the people of Lyon rediscover their local identity, to trace the history of a particular quartier, or district, and to make art accessible to everyone. One of the best examples is the Musée Urbain Tony Garnier. The outdoor “museum” comprises 30 huge murals, painted on the buildings of an HLM (Habitation à Loyer Modéré) a low-rent housing project in the Etats-Unis district of Lyon.

The apartment buildings were originally designed by French architect Tony Garnier between 1920 and 1933, part of his dream of a modern, industrial urban utopia. But by the 1980s the district was in trouble, and drugs and violence were rife. In a bid to rehabilitate the area, the residents contacted CitéCréation, and work on the murals began soon after. It was a major success. “It completely transformed the quartier,” says Bensaïd. “You can stop anyone on the street there and the response will be unanimous. It has given something back to the residents—pride—a word that can be both terrible and very beautiful. When we give pride to a space, a space which didn’t exist for the rest of the town before, for the media, we feel we have succeeded.” The surrounding district was renamed Cité Tony Garnier.

A dozen or so of the Musée Urbain murals—each some 2,500 square feet—are gigantic views of an industrial city rich with collective housing, schools, factories and clinics. A few of the murals show some of Garnier’s other architectural contributions to Lyon, including the Abattoirs de la Mouche, a huge covered meat market with a ceiling of intricate metal arches. And eight of them show conceptions of the ideal city by eight artists, each from a different country: India, Egypt, Ivory Coast, Russia, Mexico, China, Canada and the United States. The Ideal City of the US was painted by American artist Matt Mullican, whose work has often dealt with the interaction between public sign systems and personal symbols.

The second of CitéCréation’s best known projects couldn’t be more different—the nearly 13,000-square-foot Mur des Canuts, the Wall of the Canuts, in the hilly Croix-Rousse district. Canut was the nickname for a silk worker, and Croix-Rousse was at the heart of the city’s booming 19th-century silk industry. Once a working class district, it’s now one of the more expensive areas of Lyon, much sought after for its distinctive high-ceilinged apartments, quaint narrow streets, daily market and self-styled bohemian ambiance. The Canut’s Wall is a beautifully executed study of Croix-Rousse, on a grand scale. Steps march up the centre of the painting, echoing the steep flights of stairs on the slopes of Croix-Rousse. Shops and a bank can be seen at the bottom while behind them are typical Croix-Rousse buildings both traditional and modern. There is nothing special about the subject matter of this mural but it is that very ordinariness which makes it so special. You might easily cross the street to pop into the Banque Populaire, only to find as you reached for the door that it is an illusion.

Bensaïd describes it as a mirror. “You can be both inside the space and outside of it at the same time and that’s why it is so fascinating. It is this paradox which people love, but are also troubled by.” As with all CitéCréation’s murals, the subject matter was carefully considered. Bensaïd talks of finding the key when he designs a mural. The denizens of Croix-Rousse have a strong sense of their identity, and there is much talk of Croix-Rousse being a “village” within Lyon. The fresco reinforces that notion. At first, says Bensaïd, some local figures suggested that a mural of the sea would brighten up the building, but the residents of Croix-Rousse gave that idea a firm thumbs down.

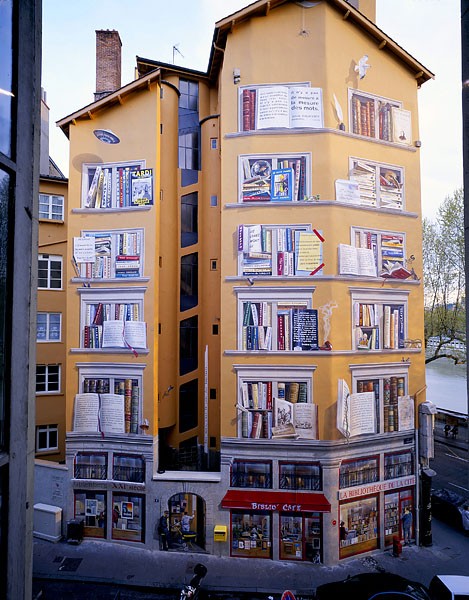

Another famous trompe l’oeil is La Fresque des Lyonnais, a mural of some 30 of Lyon’s famous figures past and present. The Roman emperor Claudius, who was born here when Lyon was the Lugdunum of Roman Gaul; the pioneer filmmaking Lumière brothers; silk weaver and inventor of the Jacquard loom Joseph-Marie Jacquard; author and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and others appear on their balconies by the Saône River. The famous Lyon chef Paul Bocuse stands in the doorway of a typical Lyonnais restaurant, and at one of his tables is crime writer Frédéric Dard. Just down the road is La Bibliothèque de la Cité, the City Library, another trompe l’oeil, which sits opposite a real second-hand book market on the banks of the river.

The Lyonnais mural is 8,600 square feet, the City Library 4,300 square feet, the Garnier and Canut murals much larger. So how do the artists create works of such size? Not surprisingly, they are broken down into more manageable small squares. Each square of a planned picture is then projected onto a wall and a sheet of tracing paper is taped over it. With a small spiky roller, the artist traces around the outline of the image, punching tiny holes in the paper. When all the sections are complete the artist sticks the squares of transparent paper on the actual wall and blows black powder through the tiny holes, effectively transferring the outlined image onto the plaster. Then the painting begins.

While most paintings are viewed at eye level, murals hundreds of feet high are seen from street level, meaning the artist has to subtly alter the perspective, tricking the eye so it looks in perfect proportion. It’s hard work, says Bensaïd. “For a start you can be 200 feet up, on scaffolding, wearing a helmet, in the wind, with the noise and pollution, for hours on end.” Hard work indeed.

Sections that are extremely detailed, like the dozens of different breads in the baker’s window on the Lyonnais mural are done indoors and pasted on later. Each mural takes two to nine months to finish. Interestingly, 80% of CitéCréation’s mural artists are women. “It’s women’s work,” says Bensaïd. “They have the patience and the resistance.”

CitéCréation has completed more than 470 murals around the world, from Canada to China. Their trompe-l’oeil mural in Shanghai, covering the exterior of a Carrefour supermarket with scenic views of France, is said to be the largest in the world at 53,800 square feet. And discussions have started about what could turn out to be the cooperative’s first mural in the United States, in Pennsylvania.

Originally published in the April 2009 issue of France Today; updated in April 2011.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY