Paris: Bracing for Change?

“The shape of a city, alas, changes faster than a mortal heart,” bemoaned Charles Baudelaire, who lived through Haussmann’s transformation of Paris. Victor Hugo gave vent to similar grief in a lament, The Fateful Years. Yet time and history proved both poets wrong: a mere glance at the scale model of Paris on display at the Pavillon de l’Arsenal suffices to take the measure of Haussmann’s genius and vision, and to admire the splendid, coherent and harmonious urban fabric he masterminded.

Alas, indeed. By the 1950s the philistines of the day began to fray and dent Haussmann’s fabric. By the 1970s, a rampant sprawl of concrete had infiltrated the city and cluttered its skyline: the Montparnasse Tower, the Zamansky Tower at Jussieu University campus in the 5th arrondissement, the Beaugrenelle development (also called Front de Seine) west of the Eiffel Tower, and La Défense—just outside the city proper—which scarred the superb vista that sweeps from the small Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in front of the Louvre down the Champs Elysées to the Arc de Triomphe. In 1977, a 37-meter (121-foot) cap was imposed on the height of new constructions, a damage control measure that remained in force for 30 years.

The 1980/90s presidency of François Mitterrand was marked by a shift to prestigious intra muros cultural monuments, leading to prodigal

spending and results of varying merit—architect I.M. Pei’s Louvre Pyramid, Carlos Ott’s Bastille Opera, Jean Nouvel’s Institut du Monde Arabe, Christian de Portzamparc’s Cité de la Musique and Frank Gehry’s American Center (now the Cinémathèque Française), a private project but certainly one of the best of the era.

By the time the four glass towers of Dominique Perrault’s controversial Bibliothèque de France—the National Library—ended Mitterrand’s spurt of Grands Projets in 1996, funds and space had run out. His successor Jacques Chirac’s 12-year presidency produced only one project of note—Jean Nouvel’s Musée du Quai Branly, inaugurated in 2006.

The turn of the 21st century, and of the new millennium, generated renewed impetus for leaders to make their marks. With the election of new president Nicolas Sarkozy (2007) and the re-election of Mayor Bertrand Delanoë (2008), Paris braced once more for changes. Some forthcoming national projects would embrace the entire Paris area, potentially even including the Seine Valley all the way to Le Havre on the English Channel. Others, initiated by City Hall, are restricted to Paris intra muros, within the city limits defined by the Boulevard Périphérique.

Towering trio

No sooner was the Council of Paris back in City Hall after Delanoë’s re-election than its members proceeded to lift the 121-foot

limit on high-rises, a decision motivated by a housing shortage, the pressures of the property market and its hoped-for windfalls, and the fear of lagging behind other cities—not least, London. Opponents of high-rise construction are dismissed as passéistes, conservatives living in the past who want to freeze Paris into a ville musée. The new cap set on office towers is 200 meters—656 feet, nearly 5 1/2 times the old limit—while residential buildings are restricted to 50 meters—164 feet. (For the record, the Tour Montparnasse is 689 feet tall, the Tour

Zamansky 295 feet.) City Hall claims reassuringly that there will be only a handful of new towers, all restricted to the city’s outer districts. But experience indicates that once precedents are set, sooner or later others follow suit.

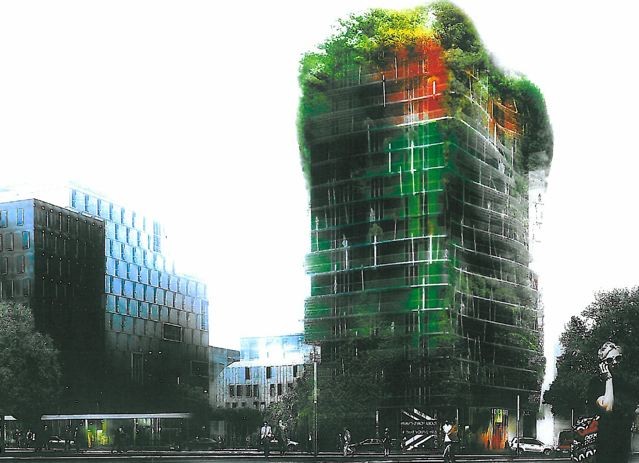

So far three sites have been picked to host new towers, although no construction dates have yet been announced. Batignolles-Clichy in the 17th arrondissement is slated to be the site of the new Supreme Court, in all likelihood housed in a tower. Masséna-Bruneseau, in the 13th, has been confirmed for an ungraceful and in no way innovative 164-foot residential tower, overgrown with vegetal sprawl along its upper stories for an ecological edge. And the Porte de Versailles, in the far 15th, will get the Tour Triangle. Designed by Pritzker-award-winning Swiss architects Herzog and de Meuron (who did Beijing’s Olympic Stadium and London’s Tate Modern museum), the massive, 650-foot-tall flattened, all-window pyramid will tower high above the old Exhibition Center, out of place and out of scale with its surroundings.

Highway high jinks

On street level, the tribulations of Parisian motorists are likely to escalate in 2012, when the Berges de Seine project kicks off and stretches of the riverside become pedestrianized. City Hall announced the project as “the reconquest of the Seine”, referring to a pre-railway golden age when the Seine teemed with harbors, shipping and washhouses. Simply said, the expressways along the river, created in the 1970s to ease the traffic flow elsewhere, will be scrapped.

On the Right Bank the expressway will be broken up by a series of traffic lights to allow pedestrians to cross to the riverbank. The lights will be installed at key intervals, notably at the Léopold Sédar Senghor footbridge that connects the Tuileries Gardens and the Louvre with the Musée d’Orsay, and the Debilly footbridge that links the Palais de Tokyo and the Musée du Quai Branly. City Hall claims that the stoplights will increase a car’s time on the route, from the Porte de Saint-Cloud to the Arsenal, by only six minutes. Time will tell.

City Hall acknowledges that at peak times the new “boulevard” will absorb some 3,000 vehicles an hour instead of the current 4,000. Meaning that thousands of daily commuters will search for alternative routes to get home—adding mileage by detouring to the already packed Boulevard Périphérique, or joining the jam on Boulevard Saint Germain.

The Left Bank riverside expressway between the Musée d’Orsay and the Pont de l’Alma will be closed to automobile traffic altogether. So while the dispossessed motorists of what current jargon calls “the France that works” pile bumper to bumper on the upper quay, “the France that plays” will stroll, push baby carriages, skate, rollerboard, scoot and cycle on the embankment below—all in peaceful cohabitation, we are told. The pollution and disturbance caused by automobile traffic will not be reduced, just displaced to the upper quay.

Day-trippers, night music

Sports facilities will also be provided on the riverside level below the Invalides and the Quai d’Orsay, and visitors will be able to stroll onto an “archipelago” of floating “islands” on the water, to observe the rich biodiversity of flotsam provided by the opaque river.

In other words, a version of the Paris Plage concept will be in permanent operation along the defunct Left Bank expressway. Given what’s happened on the Trocadéro esplanade, however, the “reconquest” of the Left Bank riverside is likely to draw street vendors and junk trade. By night, the frustrated youth of Paris, who now only dream of busy nightlife like London’s, will get a waterside disco under the Pont Alexandre III, where high-decibel music will be tolerated because no one lives nearby.

In front of the Musée d’Orsay, an enormous, unattractive, bleachers-like staircase will descend from street level to the river’s edge, arching over the riverside walkway. It will afford breathtaking views and, by the same token, will disfigure the site it’s on. In summer it will be complemented by a huge screen floating in the Seine for open-air movies. Based on past experience, opponents fear that after dark the giant stairway might lend itself to undesirable and very dodgy activities.

For the first six months, starting in 2012, implementation of the initial projects will be experimental, and reversible—although little is likely to be reversed unless the opposition wins the 2014 municipal elections. Although the announced budget is a modest €35 million, in these rocky economic times the money might be better spent on projects more useful to Parisians than tacky installations that will disfigure the banks of the Seine—a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1991.

Glass canopy

To rid the Seine of vehicles would be a welcome policy if viable alternatives were offered; replacing cars with crowds of day-trippers and the clutter of assembly-line tourism is not a welcome alternative. Delanoë calls the plan the “pacification” of the riverside, but the 30,000-odd motorists a day who are denied the expressways are less likely to be pacified than overcome by road rage up above.

The Pompidou Center and the Forum des Halles are also legacies of the 1970s. The initially controversial Pompidou ended by gaining the public’s favor, especially after its renovation in 2000. The Forum des Halles, the city’s oppressive underground subway/railway hub combined with a charmless shopping mall, was a sorry substitute for Victor Baltard’s handsome 1850s iron-and-glass central market pavilions, and it has long since become an unsavory hangout.

Although no start date has yet been set, plans are to replace the universally unloved Forum with a 150,000-square-foot Canopée designed by Patrick Berger and Jacques Anziutti—an undulating structure of louvered glass covering a new pedestrian promenade and a glass-walled music conservatory, among other things. The Canopy will face onto a vast rectangle of gardens completely redesigned by David Mangin, whose elegantly unobtrusive project for the Forum itself was chosen by a public plebiscite but nonetheless rejected by City Hall as too conservative, and replaced by the Canopy instead.

City authorities are hoping that the addition of the music conservatory, side by side with a hip-hop center, will set an example for “vivre ensemble” policies that will encourage a multicultural and multiethnic modern France for the future.

Thirza Vallois is the author of Around and About Paris, Romantic Paris, and Aveyron, A Bridge to French Arcadia. www.thirzavallois.com

Find Thirza’s books in the France Today Bookstore

Originally published in the April 2011 issue of France Today

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email