La Danseuse: American Icons of La Belle Époque

A film by Stéphanie Di Giusto charts the lives of Loie Fuller and Isadora Duncan, two American girls who found friendship, fame and fortune in turn-of-the-century Paris.

Talk about unlikely. When Midwesterner Loie Fuller – later to become a world-renowned Belle Époque dancer – first moved to Paris, little did she dream that her revolutionary Serpentine Dance with swirling silk veils and coloured lights would create a sensation at Les Folies Bergères.

But perhaps equally significant was Fuller’s discovery in 1901 of young Isadora Duncan from San Francisco, who quickly became her star protégée. Charmed by the beauty and talent of this young unknown, who danced barefoot in a flimsy white, toga-like dress, Fuller invited Isadora to join her dance troupe. It wasn’t long, however, before Duncan would upstage her teacher and go on to redefine the concept of modern dance.

The friendship and subsequent rivalry between ‘La Loïe’, as the Parisians adoringly called her, and the ambitious Isadora, is the subject of a biopic by French writer-director Stéphanie Di Giusto, La Danseuse, which premiered at the Cannes Festival last May and opened in theatres in September.

Soko and Lily-Rose Depp as Loie Fuller and Isadora Duncan. Photo: Shanna Besson/ Productions du Tresor

Fuller is played by musician-turned-actress Soko, while 16-year-old Lily-Rose Depp (daughter of Vanessa Paradis and Johnny Depp) plays Duncan. To give more insight into Loie Fuller’s character, Gaspard Ulliel (Saint Laurent, Juste la Fin du Monde) plays a foppish, ether-sniffing aristocrat, Count Louis Dorsay, a character based on various historical figures.

For Di Giusto, the idea began with a black-and-white photo of Fuller in a book. “I started researching exactly who she was and was extremely moved by her life,” says the director. “Not only was Loie a visionary dancer, but she was also a pioneer of movie-making.”

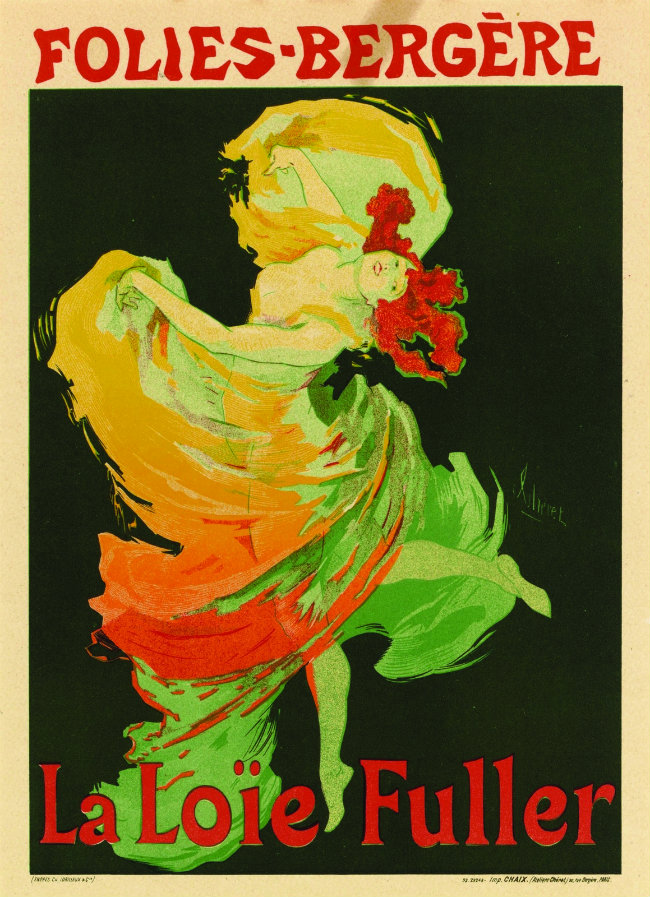

Indeed, you would easily recognise the celebrated Art Nouveau posters by Jules Chéret depicting Fuller in a whirl of fabrics. What is perhaps more surprising is that Loie was a total autodidact with no formal training in choreography, nor had she studied the scientific aspects of stage technology.

Contemporary poster advertising Loie Fuller’s show at Les Folies Bergères

Serpentine Dance

“While growing up in America, she became a huge fan of Sarah Bernhardt, and always wanted to be an actress,” Di Giusto explains. By the time Fuller was 26, she had even managed to play bit parts in various (albeit unsuccessful) theatrical productions in Chicago and New York. Today, she is best remembered for her remarkable Serpentine Dance – heightened by a mesmerising play with glaring coloured spotlights, phosphorescent gases and dyes – to the point of ruining the dancer’s eyesight.

But was it really dance?

These ground-breaking effects were created by the vertiginous combination of experimenting with light, and manipulating the voluminous folds of her white dress (which extended out to the line of the arms). The result: a frenzied succession of ever-changing shapes that resembled flowers or plants that broke the mold of traditional ballet.

And it was precisely this elaborate play with fairy-like glowing colours, mirrors and movement that prompted critics to compare her work to other precursors of cinema, such as photographers Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge.

Loie Fuller

Symbolist Emotion

Meanwhile, many prominent figures, including scientists Pierre and Marie Curie, sculptor Auguste Rodin to poet Stéphane Mallarmé, hailed Fuller as the incarnation of pure Symbolist emotion. However, when Mallarmé eventually met the sublime Loie in person, she was not the ethereal sylph he had expected. His obvious disappointment was a blow to the star, who, out of costume, was a robust woman with a plain face.

“Fuller was very hurt by this,” Di Giusto says. “There was nothing regal about her. Apparently, she was very nervous and laughed all the time. And she didn’t know how to use her charm, unlike Isadora, who most certainly did.”

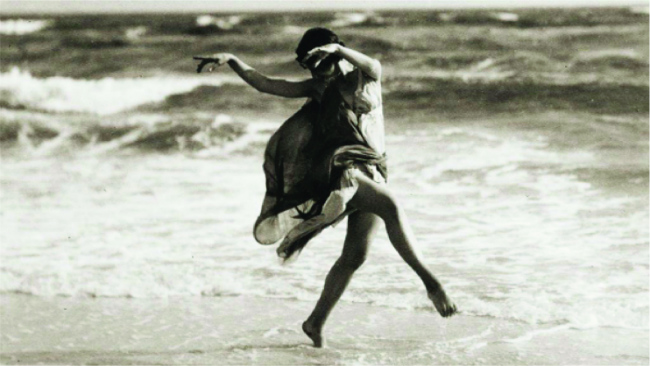

Which, given their respective backgrounds, was quite understandable. Isadora Duncan – whose famous ‘natural’ dancing was expressed spontaneously with rhythms inspired by the sea and the solar plexus – could not have been more different from her Midwestern friend and rival. However, Loie had been brought up with no schooling on an Illinois farm, whereas Isadora’s unconventional artistic education began at an early age. What they shared was a fearless will to get ahead.

Mary Dora Gray, daughter of a California senator, married the cultivated (but inveterate gambler), Scottish-born Joseph Charles Duncan, but filed for divorce shortly after Isadora – the youngest of four children – was born, in 1877. Whisking the family off to Oakland, Mary took it upon herself to instruct them in music, poetry and dance. By the age of six, Isadora was studying classical ballet; by ten, this decidedly headstrong young girl had decided to drop out of school, declaring that it was “absolutely useless”, and busied herself with more serious pursuits in improvisational dance. Along with her sisters and brother, Raymond – who later opened a school of ‘complete living’ in Paris and was known as an artist, dancer, poet and philosopher – Isadora’s bohemian lifestyle prepared her for the artistic explosion of the European avant-garde.

Isadora Duncan

Director Stéphanie Di Giusto. Photo: Shanna Besson/ Productions du Trésor

To London and Paris

After a debut performance in New York (wearing her trademark floating, transparent Classical Greek tunic), Isadora and her mother set off for a brief stint in London, and then went on to Paris in March of 1900. Fascinated by Loie Fuller, who was featured at the theatre of the World’s Fair Exposition, Isadora arranged a meeting through a mutual American friend, singer Emma Nevada.

In The Dancer, Stéphanie Di Giusto takes a number of liberties with biographical details for the sake of drama. Though the circumstances aren’t completely accurate (in the movie, Isadora is hired as a replacement for an ailing dancer in the troupe), the ‘seduction’ of Loie is one of the strongest moments in the film. Duncan strips naked and proceeds to prance and wave her arms around the château’s empty rooms, jumping up on furniture and whirling sans musique to her own inner rhythms.

The strong erotic overtones in this scene between Loie and Isadora are, in fact, not invented. Fuller, who had long since divorced her wealthy American husband, was a lesbian, and presumably drawn to Duncan’s charms. “When Loie meets Isadora, she realizes that this girl is everything that she can’t be – a true dancer, not a slave to her body – and Loie wants to own her,” Soko observes.

A scene from “La Danseuse.” Photo: Shanna Besson/ Productions du Tresor

According to one biographer, who wrote in the museum catalogue, Isadora Duncan 1877-1927: Une Sculpture Vivante (Paris Musées 2009), Isadora joined the troupe but led Loie on with a flirtatious promise of a romance. Before long, she was said to have cruelly blackmailed Fuller and demanded money to advance her own career. This moment reveals a scheming side of Duncan’s personality that went hand in hand with her unbending ambition to succeed.

Casting Soko as Loie, says Di Giusto, was an obvious choice. “I’ve known her for a long time, but first and foremost, she’s also an artist and very different from the standard young actresses you see today.”

Soko as Loie Fuller. Photo: Shanna Besson/ Productions du Tresor

To prepare for the part, Soko says she trained strenuously for seven hours a day (“The choreographer really whipped my butt into shape”), which made her appreciate the strenuous physicality of Fuller’s art. “Loie would practically faint at the end of every performance and had to rest for three days in between,” the actress says. “I don’t know how she did it. Some days after rehearsal, I was so beat I could barely bend over to put my socks on.”

Finding Isadora was more difficult, admits Di Giusto. “I wanted a 16-year-old actress – and the list isn’t very long.” Only two months before the shoot, the director flew to Los Angeles to meet Lily-Rose Depp, and was immediately won over by the actress’s “astounding capacity to abandon herself”.

Isadora Duncan in Bellevue

Elaborate Dance Scenes

Though this is Lily-Rose’s first semi-major acting role, the actress says that she read everything she could about Duncan, including old archives from the turn-of-the-century Paris newspapers. “Isadora really wanted everything to come from the heart; it was all very natural,” says Depp. “She was really the first person to show her body.” (Some of Lily-Rose’s elaborate dance scenes were shot with a double, but she says she had no qualms about portraying Isadora in the nude.) “I also had fun playing the devilish side of Isadora,” says Depp. “Basically, under the sweet young girl façade, she was always looking out for herself.”

The film ends just as Duncan’s career begins to soar, and Fuller (who will live peacefully with her business partner, Gabrielle, for the rest of her days), gradually accepts that she will not be able to perform for ever. Though Loie eventually returned to America as an acclaimed artist, her school of dance became a way for the artist to continue what she had begun: a revolution in modern dance. She died at the age of 65 in Paris and her ashes are buried in Père Lachaise.

Today, we are more familiar with Duncan’s spectacular rise and fall, from adored goddess to a disillusioned woman with debt and alcohol problems. The tragic events that occurred later in Isadora’s life – the accidental drowning of her children, her failed romance with Paris Singer (heir to the inventor of the sewing machine), her subsequent disastrous but short marriage to reckless dandy Russian poet Sergueï Essénine, who committed suicide thereafter – took an overwhelming toll on her mental health. In 1927, at the age of 50, she met her end by strangulation of a long scarf caught in the wheels of a Bugatti on Nice’s Promenade des Anglais.

Ultimately, the film reminds us that the greatest link between these two worshipped American dancers was their shared bold pioneering spirit – they had the right stuff, so to speak, to become a shining star, but it was only possible in turn-of-the-century Paris.

Or, as Fuller once aptly quipped: “I was born in America but made in France.”

From France Today magazine

La Danseuse, directed by Stéphanie Di Giusto

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *